Chris Keyes was a third-year undergraduate at Colorado State in 2014 when one of his professors in a health economics class gave a lecture on the economic costs of lead exposure.

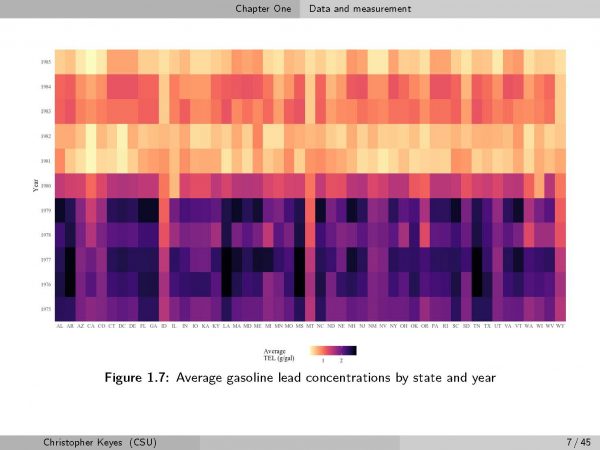

That professor, Sammy Zahran in the Department of Economics, suggested that if one had data on where, when, and how much lead was emitted from gasoline in the decades leading up to the switch to unleaded in 1990, one might be able to calculate the long-term effects of lead exposure, analyzing whether people who grew up in high-lead areas saw any lasting negative health or cognitive outcomes.

Of course, tracking down all of that data — not just on the lead levels but on the people who were exposed to it — would take years of sifting through thousands of pages of government reports.

Keyes earned his Ph.D. in economics from CSU in December 2020. His dissertation is about the effects of lead exposure on human health, and he accomplished what Zahran had suggested six years ago: Keyes has established not just a correlation, but a causal relationship, between a region’s level of lead and the degree to which the people who grew up there suffered adverse health and cognitive effects from elevated levels of lead in their blood.

Keyes’ findings: the higher the level of lead emissions in a given area, the more likely it was that individuals from those locations experienced complications at birth, or, later in life, scored lower on standardized tests or exhibited abnormal behaviors indicating that a key area of their brain suffered as a result.

Lead is still a problem

Many people view lead as a concern of the past, given that leaded gasoline and lead-based paint have been phased out in the U.S., but Zahran says the lead emitted by cars over all those decades has been deposited in soils, and it can still be kicked up into the air and inhaled.

“All major cities are covered with this stuff,” he explains. “Lead is not a rear-view problem, it’s still with us.”

"Lead is not a rear-view problem, it’s still with us."

At the outset, Keyes and Zahran didn’t know how much work would be involved in analyzing this problem.

"I don't think either of us could have anticipated how laborious the data collection process would be," Keyes says. “I was tracking down tables in dusty 40-year-old government reports, and that actually ended up being a three-year project.”

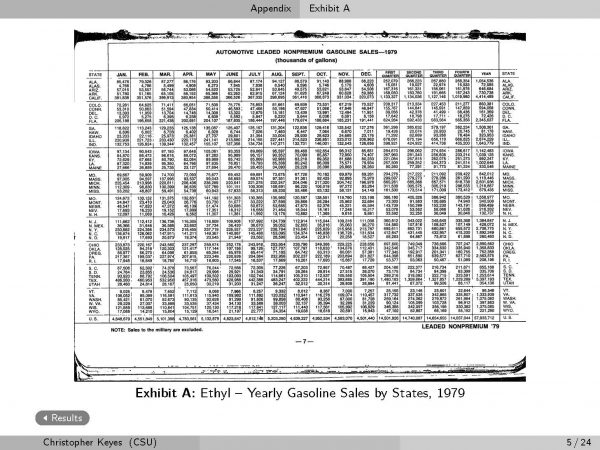

First, Keyes tracked down the amount of leaded gas sold in every state, by year, as far back as 1950. Then Keyes and Zahran had to identify the concentration of lead contained in that gasoline sold, because the amount of lead in gas varied from producer to producer. From there, they created a weighted formula to calculate the amount of lead emitted annually in each state, accounting for the fact that states transitioned to unleaded gas at different rates.

“Chris is right that we underestimated the effort involved,” Zahran adds. “The quantification of archival records is common in the fields of economic history and cliometrics, and the two of us have developed a deeper appreciation for this kind of economic research.”

Patient research

To assess the possible impacts of lead on human health, Keyes and Zahran relied on three primary sources: the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, or NHANESII; the National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1997, or NLSY97; and natality data from the National Vital Statistics System of the National Center for Health Statistics.

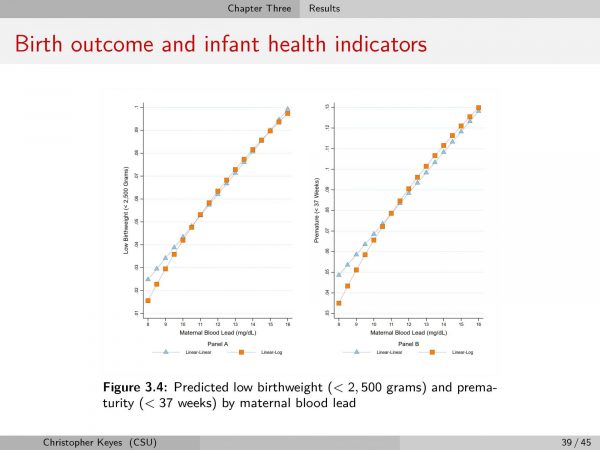

NHANESII, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 1976 to 1980, collected demographic, socioeconomic, employment, household environment, and physiological data for more than 20,000 people. About half of those respondents also participated in hematology and biochemistry testing. That provided Keyes and Zahran the levels of lead in the blood of those respondents, including women of reproductive age. According to Zahran, these data were key because lead in a mother’s bloodstream can have negative impacts on their babies, resulting in low birth weights, premature births and lower scores on the Apgar test, a method for quickly assessing the health of newborns.

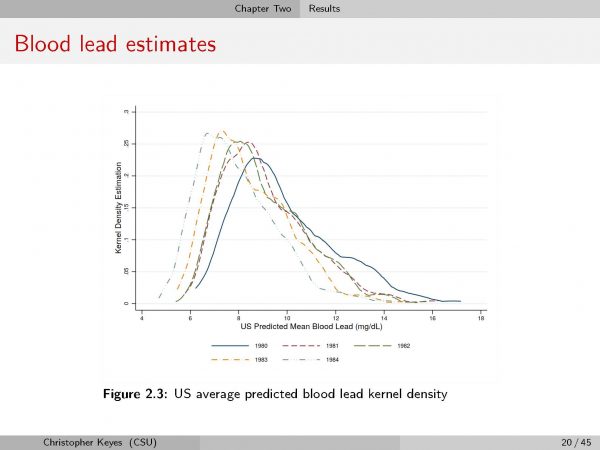

The NLSY97 began with more than 12,000 individuals born between 1980 and 1984, and is an ongoing survey that tracks labor-market activities and significant life events of individuals over their lifetime. Keyes and Zahran used the NLSY97 results to track individuals’ performance on standardized tests and their willingness to take risks. Childhood lead exposure has been associated with decreases in IQ and in the volume of the brain’s cerebral cortex, or “gray matter,” which is the seat of executive judgment and decision-making, including one’s tolerance for risk.

The natality data provided Keyes and Zahran with more than 6 million records on live births in the United States, including the child’s date of birth, the mother’s place of residence during her pregnancy, key demographic information, and a suite of health outcomes pertaining to the child.

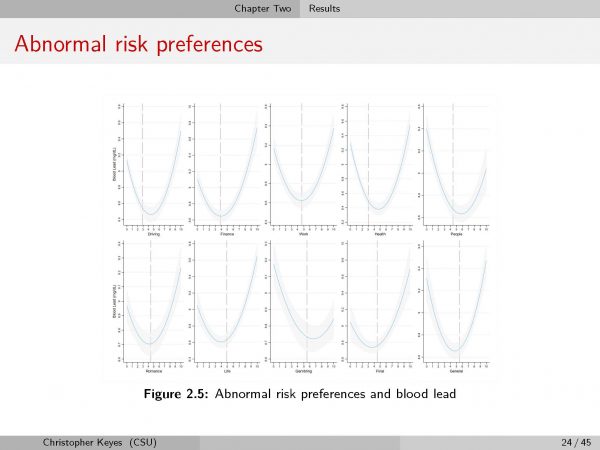

Establishing a cause

Using all of these data, Keyes and Zahran could compare measures of a person’s health and even cognitive ability with the levels of lead emissions in the area where they were born and grew up. They found a strong connection: The more lead individuals were exposed to, through their mothers or as children, the more likely they were to have complications at birth, lower standardized test scores, and deviations from the norm when it came to risk-taking. Zahran and Keyes found that people from areas with high lead emissions were more likely to participate in risky behaviors in young adulthood compared to the average.

“It turns out that those individuals with higher lead exposure in childhood were more extreme in the way they prospected risk in adulthood,” Keyes says. “When we saw this econometric relationship, we knew we were on to something, as it was consistent with prior research on the abnormal cognition of lead-exposed people.”

“These effects in adulthood are an echo from early childhood, due to exposure to this pollutant,” Zahran adds.

The more lead individuals were exposed to, through their mothers or as children, the more likely they were to have complications at birth, lower standardized test scores, and deviations from the norm when it came to risk-taking.

Connecting emissions data

And they have created what is believed to be one of the only digitized collections of comprehensive government data on lead emissions by year and state, which they say can be a useful tool for future projects. By linking lead emissions data with other administrative datasets, Keyes and Zahran hope to study other long-term health and economic consequences of lead exposure that, to date, resisted quantification.

“We know we have a hammer; now we just need more nails,” says Keyes, who works for a local data science startup company. "The data collection effort was well worth it. Both from a technical standpoint, vis-a-vis learning the necessary statistical and econometric techniques, but also in developing a substantive understanding of the long reach of lead exposure and the burden on public health."

By quantifying the health and cognitive effects of lead exposure, Zahran says, economic research of this kind can inform current policy debates facing the country, like whether we phase out leaded aviation gasoline, remediate the accumulation of lead in surface soils, and replace leaded service lines that deliver water to our homes. Knowing the costs of lead exposure is a critical first step in rational discussion of these policy options.

“The decision to phase out leaded gasoline has conferred genuine health and cognitive benefits on subsequent generations of children and adults in America. It’s a gift that keeps on giving,” says Zahran.

The two plan to publish their results in upcoming journal articles.