Black Elk’s Peak in the Black Hills National Forest in South Dakota. Photograph by HTurne/Alamy

A lengthier interview is published on the Department of Philosophy website

In her quest to heal the social and psychic scars of colonization, exclusion, and marginalization, Gloria Anzaldua argues for racial inclusivity in Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987). From her personal and political positioning at the intersection of white, Mexican, and indigenous cultures, Anzaldua envisions the creative cross-pollination of identities that can birth a “mestiza consciousness”—a consciousness of the Borderlands.

This consciousness emerges, in part, by the overcoming of a “counterstance [that] locks one into a duel of oppressor and oppressed.” For Anzaldua, this is “not a way of life.” Instead, she encourages us to “leave the opposite bank, the split between the two mortal combatants somehow healed so that we are on both shores at once and, at once, see through serpent and eagle eyes.”

In her advocacy of coalitions and the nurturing of allyship, Anzaldua encourages us to “meet on a broader communal ground” because “we need to know the history of [others’] struggle and they need to know ours.” In the spirit of learning, knowing, and understanding, two philosophy students came together to listen to one another and, as a result, broaden their consciousnesses together.

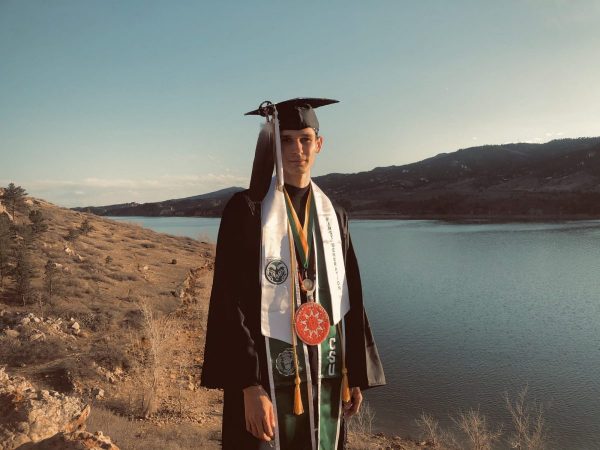

Recent philosophy graduates, Maeve Marley, an Irish American student from Denver, and Weston Jones, CLA Outstanding Grad, Oglala Lakota from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota are separated by culture but united in their travels across and through borders close to home. In this dialogue, they discuss Native American life, different ways of knowing, and the interconnections that bind us together.

The following dialogue was edited for clarity and brevity.

Philosophy as the Bridge between Worlds

Maeve: When you go home, what are the things that you tell your family about college, or what are the questions that they ask you about college?

Maeve: When you go home, what are the things that you tell your family about college, or what are the questions that they ask you about college?

Weston: When I go home, my family doesn’t really understand what college is. Because when I say that I’m first generation, I’m not just first generation of my immediate family. I’m first generation of my uncles, my aunties, my grandmas… I’m first generation of my whole community. They don’t even know what college really is. They just know you go to college. It allows you to get a good job. It allows you to make more money. They don’t know the culture of college.

Weston: When I go home, my family doesn’t really understand what college is. Because when I say that I’m first generation, I’m not just first generation of my immediate family. I’m first generation of my uncles, my aunties, my grandmas… I’m first generation of my whole community. They don’t even know what college really is. They just know you go to college. It allows you to get a good job. It allows you to make more money. They don’t know the culture of college.

Maeve: Why did you decide to go to college?

Maeve: Why did you decide to go to college?

Weston: In my high school years I was really opposed to Western education. I felt like I could learn more in my community than I could if I went off and learned from some White person telling me about education. I really thought I could learn more at home by spending more time in traditional ways and learn more traditional stuff as opposed to Western stuff.

Weston: In my high school years I was really opposed to Western education. I felt like I could learn more in my community than I could if I went off and learned from some White person telling me about education. I really thought I could learn more at home by spending more time in traditional ways and learn more traditional stuff as opposed to Western stuff.

I decided to go because my sister and I were arguing about whether education could help save the world. We were discussing whether education could help the people on our reservation. I said no. I said the only way that we can do and help our people is study traditional knowledge and forget about Western education and forget about college.

Then, my sister said something that stuck with me. She said we need to combine traditional and Western thought. We need to combine them together because we live in a world that is essentially two worlds. When I go home, that’s one world, but when I’m at school, that’s another and these worlds have to coexist, right? Because that’s the world that we live in.

We need to combine traditional and Western thought. We need to combine them together because we live in a world that is essentially two worlds.

I can’t resort back to my traditional knowledge in the way that I could hundreds of years ago. I can’t just go live in a teepee in the middle of a park. I can’t just go out and hunt anywhere I want to go hunt; our land rights were taken away, our hunting rights were taken away, our fishing rights were taken away. We have to be able to coexist in two worlds essentially.

My sister and I were both crying in this conversation. She was frustrated that I didn’t get it, and I was frustrated that she didn’t get it. But we came to a common ground, and I thought on the coexistence of two worlds and combining traditional and Western thought together to thrive in this modern world. At that moment, I decided to go to college.

Maeve: Do you feel like you’ve been able to do that in college—to combine the two worlds? Especially when you’re at CSU, do you feel like you can be Oglala Lakota?

Maeve: Do you feel like you’ve been able to do that in college—to combine the two worlds? Especially when you’re at CSU, do you feel like you can be Oglala Lakota?

Weston: It was really hard at first. I was looking for a bridge. Where is this bridge my sister was talking about? Where is this bridge between Western and traditional ways? I was looking at different degrees. I was looking at different majors. I was looking at different educational institutions. I was looking all over. And that’s when I fell upon philosophy.

Weston: It was really hard at first. I was looking for a bridge. Where is this bridge my sister was talking about? Where is this bridge between Western and traditional ways? I was looking at different degrees. I was looking at different majors. I was looking at different educational institutions. I was looking all over. And that’s when I fell upon philosophy.

I discovered that philosophy was very similar to my traditional knowledge in my traditional ways, and all I had to do was translate it. I had to be able to translate what these philosophers—these White philosophers, these Chinese philosophers, all these different philosophers throughout the ages—were saying. How is what they’re saying similar to what my ancestors said?

Once I was able to translate them and connect them in a way, then I found that bridge my sister was talking about. I found that bridge between Western and traditional thought: philosophy via translation.

Native American Knowing

Maeve: Do you consider yourself to be a philosopher in the same way that you consider your ancestors to be philosophers? Where do you see similarities and differences?

Maeve: Do you consider yourself to be a philosopher in the same way that you consider your ancestors to be philosophers? Where do you see similarities and differences?

Weston: My ancestors didn’t have to go the extra step that I’m going through right now: the extra step of translation. My ancestors would think a thought, say it, and then that was it. Right now, if I think a thought, I have to translate that thought two ways. I have to translate it into a Western way so that I have credibility. Because nothing you say has credibility unless it’s said in a Western manner and essentially in English. And then I also have to go home and say it to my family, something that they will be able to comprehend in a traditional way. I have to go the extra step of living in two worlds compared to my philosopher ancestors back in the day.

Weston: My ancestors didn’t have to go the extra step that I’m going through right now: the extra step of translation. My ancestors would think a thought, say it, and then that was it. Right now, if I think a thought, I have to translate that thought two ways. I have to translate it into a Western way so that I have credibility. Because nothing you say has credibility unless it’s said in a Western manner and essentially in English. And then I also have to go home and say it to my family, something that they will be able to comprehend in a traditional way. I have to go the extra step of living in two worlds compared to my philosopher ancestors back in the day.

Maeve: Do you have an example of philosophy in translation? I’m also wondering about how your tribal culture informed your approach to philosophy.

Maeve: Do you have an example of philosophy in translation? I’m also wondering about how your tribal culture informed your approach to philosophy.

Weston: Yes, there’s this Oglala Lakota woman named Charlotte Black Elk. She’s the great granddaughter of Chief Black Elk, the medicine man and holy man. Charlotte Black Elk is a really well-educated woman in both traditional and Western education. She spoke some words one time that I hold true all the time: there’s a difference between knowledge and knowing. Western thought focuses on knowledge, while traditional and indigenous thought emphasizes knowing. Western thought has knowledge about certain things and indigenous people have knowing about certain things.

Weston: Yes, there’s this Oglala Lakota woman named Charlotte Black Elk. She’s the great granddaughter of Chief Black Elk, the medicine man and holy man. Charlotte Black Elk is a really well-educated woman in both traditional and Western education. She spoke some words one time that I hold true all the time: there’s a difference between knowledge and knowing. Western thought focuses on knowledge, while traditional and indigenous thought emphasizes knowing. Western thought has knowledge about certain things and indigenous people have knowing about certain things.

I can use lightning as an example. The difference between knowledge and knowing is value. When the Western world was colonizing North America and creating advancements in science, they put a value on their knowledge and they said the value of our Western knowledge is far greater than your knowing of indigenous science. For example, my people hold a ceremony every spring and we go to the top of Black Elk’s Peak in the Black Hills National Forest in South Dakota. We go to the top and we have a simple ceremony. We’re welcoming back the lightning every spring, and we’ve been doing this for thousands and thousands of years on the spring solstice. That’s what we do. We welcome back lightning because we knew something about the lightning—that it helps the earth. We knew that when lightning came, spring came. The birds came back; the flowers grew; the grass turned green. Life was rejuvenated when lightning came. That’s what we know as indigenous people. That’s how we know that lightning is sacred.

But then you go into a Western science class and learn that lightning energizes the particles in the atmosphere and lightning creates nitrogen oxides. And, they say, “this knowledge of lightning creating nitrogen oxides in the Western sense is more valuable than your ceremony. Your ceremony on top of this hill is a prehistoric, savage way. This makes no sense to us.”

There’s a claim there about value, with knowledge being more valuable than sacred knowing. The true essence of it is that there is no difference in value. My ceremony means just as much as advancements in science.

Maeve: I’ve done that hike to Black Elk’s Peak. I went with the Pine Ridge Girls’ School. And we did a ceremony where we tie colorful flags to trees, perhaps it was part of the same ceremony. My supervisor at Trees, Water, and People, Dr. Valerie Small, who herself is Crow, is very well educated in both traditional and Western science. And I think the biggest thing that I’ve been able to observe, and this rings true with what you said, is that indigenous knowing and indigenous science include people as part of the knowing. But just a part of it.

Maeve: I’ve done that hike to Black Elk’s Peak. I went with the Pine Ridge Girls’ School. And we did a ceremony where we tie colorful flags to trees, perhaps it was part of the same ceremony. My supervisor at Trees, Water, and People, Dr. Valerie Small, who herself is Crow, is very well educated in both traditional and Western science. And I think the biggest thing that I’ve been able to observe, and this rings true with what you said, is that indigenous knowing and indigenous science include people as part of the knowing. But just a part of it.

This is opposed to how we can view Western science. We can start to question Western science and ask: why do we isolate things and then observe them in isolation? Why would you take it out of its surroundings and watch it and then say we know what it is? Isn’t that taking it away from what it is? The lightning, the ceremony, that’s a part of it all. The ceremony you have when the lightning comes back is part of the lightning; it’s part of the rejuvenation. It’s part of the whole thing. I just thought that was really cool. I had never heard it put in terms of knowledge and knowing, but I think I get it.

Maeve: What is an experience that you think everyone needs to have?

Maeve: What is an experience that you think everyone needs to have?

Weston: I’m going to get philosophical on this one. I believe everyone should meditate on their cosmic position. This is often overlooked in modern society. We disassociate ourselves from our position on this earth, underneath the stars; we disassociate from plants, from the animals, from our relatives, from other people.

Weston: I’m going to get philosophical on this one. I believe everyone should meditate on their cosmic position. This is often overlooked in modern society. We disassociate ourselves from our position on this earth, underneath the stars; we disassociate from plants, from the animals, from our relatives, from other people.

We should all ask ourselves: What is your relationship? What is your position in the universe? What are you doing? Where are you going? What are you going to do? What are you going to leave behind when you die? What are you going to do so that the generation coming up can have something? What is your purpose?

I feel like everyone needs to find their position on this Earth. Everything is essentially connected in one way or another, big or small, and you need to find your position in that web.

Interconnection

Weston: Another piece of this is our responsibility to this interconnection. I think seven generations ahead of me and seven generations behind me. I have this responsibility two ways, in both directions to better live on this earth. This includes philosophy and the thoughts we leave behind. One example of this is the work I’m doing to reestablish the Lakota language that was once lost, for both my ancestors and the younger generations. That’s my responsibility. I could take my philosophy degree and go do something that is irrelevant right now, that doesn’t help my people and that doesn’t pertain to my responsibility. I could disassociate myself from my connection with everything that is, but I can’t do that. I need to fulfill my responsibilities to my people and this land.

Weston: Another piece of this is our responsibility to this interconnection. I think seven generations ahead of me and seven generations behind me. I have this responsibility two ways, in both directions to better live on this earth. This includes philosophy and the thoughts we leave behind. One example of this is the work I’m doing to reestablish the Lakota language that was once lost, for both my ancestors and the younger generations. That’s my responsibility. I could take my philosophy degree and go do something that is irrelevant right now, that doesn’t help my people and that doesn’t pertain to my responsibility. I could disassociate myself from my connection with everything that is, but I can’t do that. I need to fulfill my responsibilities to my people and this land.

Maeve: I remember when I first heard the term seven generations back and seven forward. It was Henry Red Cloud and he was talking about the work that they’re doing. They build solar power stoves and do other kinds of climate change related work. He was just so clear about serving the seven generations ahead and the seven generations behind. And I thought that if everyone thought like this and everyone cared like this, we would not be here not be in this mess that we’re in today—environmentally and otherwise.

Maeve: I remember when I first heard the term seven generations back and seven forward. It was Henry Red Cloud and he was talking about the work that they’re doing. They build solar power stoves and do other kinds of climate change related work. He was just so clear about serving the seven generations ahead and the seven generations behind. And I thought that if everyone thought like this and everyone cared like this, we would not be here not be in this mess that we’re in today—environmentally and otherwise.

Weston: Exactly.

Weston: Exactly.

Ashby: What do you think is the best way that we can live together and share land in a way that’s good for the earth and people?

Ashby: What do you think is the best way that we can live together and share land in a way that’s good for the earth and people?

Weston: Like I said, we live in two worlds, so we can’t resort back to the ways things were. But to native people, we hold certain places on this continent as very sacred. We hold Horsetooth as a sacred mountain. But nobody knows that. Nobody knows that certain areas are sacred. Because we live in these two worlds, all we want as indigenous people is to be in the conversation.

Weston: Like I said, we live in two worlds, so we can’t resort back to the ways things were. But to native people, we hold certain places on this continent as very sacred. We hold Horsetooth as a sacred mountain. But nobody knows that. Nobody knows that certain areas are sacred. Because we live in these two worlds, all we want as indigenous people is to be in the conversation.

One of the things that we, as environmental activists and justice seekers and Indigenous people, are asking for is name changes. Change Horsetooth to a traditional Lakota name. Resort back to its original name. In the Black Hills, our sacred mountain was called Harney Peak, named after an explorer colonizer who supposedly discovered this mountain and built a fire tower at the top. And then we called that whole mountain Harney Peak for a hundred years. Now, when we call it Black Elk’s Peak, people start recognizing it as indigenous land. This is how we can begin to recognize what sacredness of the land means. Maybe the closest understanding a White [non native] person has is walking into a church. You’re now in a sacred holy place. To Indigenous people, this whole river is sacred; this whole mountain is sacred; this whole cave is sacred. All we’re asking is just to be in the conversation about our land.

Building Relationship, Building Understanding

Weston: Maeve, what sparked your initial interest and motivation to know more about Indigenous culture?

Weston: Maeve, what sparked your initial interest and motivation to know more about Indigenous culture?

Maeve: I remember when I was in high school, I did a research paper on Indigenous people and forced assimilation, boarding schools, and the Dawes Act. I started to question why I didn’t know about this history and my friends didn’t know this history.

Maeve: I remember when I was in high school, I did a research paper on Indigenous people and forced assimilation, boarding schools, and the Dawes Act. I started to question why I didn’t know about this history and my friends didn’t know this history.

My dad is first-generation American from Ireland. The Irish were among the first people that the British colonized. On the other side, my mom’s family came over on the Mayflower. There’s definitely a large history with colonization and benefiting from colonization on my mom’s side of the family. I’m trying to understand that and feel proud about where I came from in some ways. For example, I know my great, great, great, great, great grandfather fought in the American Revolution. That’s pretty cool, but what else happened that I may not be so proud of?

When I started doing Alternative Break and I applied to be a site leader, they assigned me to the trip to Pine Ridge. Immediately, I declined because I didn’t think I should do that. I thought that they should pick someone who is Indigenous or knows a whole lot more than I do. It turns out they didn’t have a native person who could lead the trip, so I decided to do it. I did a lot of research and met with many folks before the trip, like Dr. Doreen Martinez and members of NACC. And, I had been working with Trees, Water, & People who have a long-standing relationship with Henry Red Cloud. I started interning with Trees, Water & People because I really wanted to know more and understand more before I was supposed to be the person leading others.

Leading this trip was the one of the best things I could have done to learn more about something that I think that everyone should know about. And your tribe is just one of so many. I just took the opportunity as it was presented to me.

Weston: I don’t want to overgeneralize, but if you truly know one tribe with your heart on a human-to-human level you pretty much know all other tribes. We may say things in different ways in a different language, but we still welcome back the lightning and have our certain ceremonies. We have all been on this continent together, kind of as one big family for thousands of years. There are many differences, but we share this similarity as well.

Weston: I don’t want to overgeneralize, but if you truly know one tribe with your heart on a human-to-human level you pretty much know all other tribes. We may say things in different ways in a different language, but we still welcome back the lightning and have our certain ceremonies. We have all been on this continent together, kind of as one big family for thousands of years. There are many differences, but we share this similarity as well.

Weston: What do you think is the primary thing you learned from your trip?

Weston: What do you think is the primary thing you learned from your trip?

Maeve: My whole attitude was that we are doing this trip and the related service work in exchange for learning. I think we all understood that there was a lot more to learn but that we had to listen for what was being taught in each moment. We learned more about the horrible crimes committed against Indigenous people and the ways in which our education system manipulates those facts. We also learned about sustainable energy practices.

Maeve: My whole attitude was that we are doing this trip and the related service work in exchange for learning. I think we all understood that there was a lot more to learn but that we had to listen for what was being taught in each moment. We learned more about the horrible crimes committed against Indigenous people and the ways in which our education system manipulates those facts. We also learned about sustainable energy practices.

I think I came back and I understood knowing better, similar to what you were saying, Weston. I came back wanting to understand better where I am and who I am. I felt different about what I was learning and why I was learning it. And, I was intrigued listening to Henry Red Cloud talk, and hearing about this other way of experiencing the world.

Weston: I think native spirituality in its most basic form is about acknowledgement: acknowledgement of the stars; acknowledgment of the summer solstice; acknowledgement of spring, summer, winter. It’s about the way the eagle is the highest bird in the sky. We acknowledge that, and that’s why we wear its feathers in our hair—to acknowledge this as sacred because it is physically the highest thing in the sky. It’s an acknowledgement of the natural world, of the things around us, of our connection to everything.

Weston: I think native spirituality in its most basic form is about acknowledgement: acknowledgement of the stars; acknowledgment of the summer solstice; acknowledgement of spring, summer, winter. It’s about the way the eagle is the highest bird in the sky. We acknowledge that, and that’s why we wear its feathers in our hair—to acknowledge this as sacred because it is physically the highest thing in the sky. It’s an acknowledgement of the natural world, of the things around us, of our connection to everything.

Maeve, you said you came back and just thought about things a little bit differently. But the true philosophical aspect of that experience is some kind of self-transcendence. Other peers might have gone and just said they went on a trip to some crazy impoverished place and thought our ways were weird. But you found the beauty in that, and you applied it to your life. It sounds simple, but in reality it’s a big thing. That’s why you’re a prime example of how an ally could be.

Navigating Borders

From water to dance, science to film, clay to gender, the liberal arts helps us navigate the borders in our lives that are physical, metaphorical, or cultural.