Border marker between China and Myanmar from 1960. Photo by Jiajia Wang.

Back in 2009 I was traveling in China’s Yunnan province, famed among international backpackers for its mountainous landscape, ethnic diversity, and chill border towns. This region in the southwest of China has been a transnational crossroads for centuries: to the west were the high altitudes of the Himalayas over which we could cross Tibet to reach India and Nepal; southward would take us to Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar in Southeast Asia. We arrived in the village in Ruili County that the Chinese tourism industry has named “One Village Two Countries” because the China-Myanmar border established in 1960 cuts right through, slicing it into two national halves: one Chinese, the other Burmese.

We arrived just in time for the three-day “Water Splashing” festival celebrated among Tai-speaking communities from South China all the way to Thailand. Laughing children ran through openings in a gate that divided the village, to splash water on their friends and family on the Myanmar side of the border. We were literally in the borderlands, but the border only traces back to 1960. There are similar “one village two countries” localities in other parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe, but I have been interested in the China-Southeast Asia borderlands for more than two decades.

The borders that have divided and defined China, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar have shifted over the centuries, as kingdoms, empires, and modern nations competed for territory. For much of history, there have not even been clearly defined borders - only frontier zones, blurry spaces claimed by diverse polities. For hundreds of years, peoples have migrated not across national borders, but from one imperial domain to another.

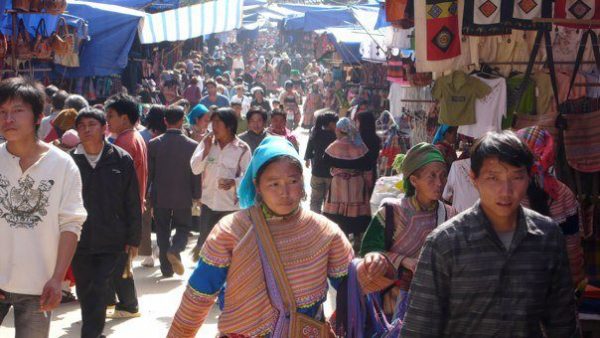

Market towns in Lao Cai Province, Vietnam

Identifying the Colorful Costumes

About a year after my trek to the village that straddled the China-Myanmar border, I visited another border area—Sapa, in Lao Cai Province, on the Vietnam side of the Vietnam-China border, known during the time of French colonialism as the Alps of Indochina and also for a border war between China and Vietnam in 1979. Sapa, like much of the highland areas of Southeast Asia, is a mosaic of ethnicities, hill tribes identified by their colorful dress, among them, Hmong, Red Dao (Iu Mien), Black Dao (Kim Mun), Tay, Giay, Muong, Thai, Hoa, and Xa Pho, each grouping identified by a different costume. Years earlier, while conducting fieldwork in a Yao village in northern Thailand, a woman who was selling embroidery told me: “If we don’t wear our traditional clothing, no one can tell we are Yao.”

My research for more than two decades has been the Red and Black Dao, known in Chinese as the Yao, a label used by officialdom to identify numerous groups across South China and beyond, similar to how the label “Miao” has included Hmong and numerous other upland groups. Going back to my dissertation research, I was fascinated in the longue durée process of how local officials identified peoples in the southern reaches of Chinese empires as “Yao.” As long ago as the 12th Century C.E., Chinese officials identified diverse groups of Yao people according to their customs and costumes, a practice that has continued up to the present.

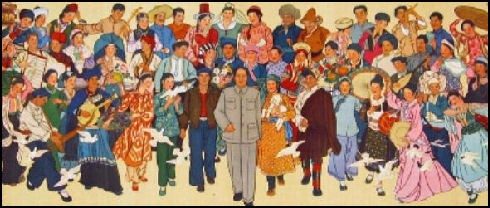

If you travel across Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, which shares a provincial border with Yunnan in the west and a national border with Vietnam in the south, you might just chance upon the White Pants Yao, the Red Hat Yao, the Indigo Yao, the Pointed Hat Yao, and the Flat Hat Yao, among other Yao groupings, some that speak the same language, others different. This way of identifying Yao subgroups is in line with how the People’s Republic of China has represented itself since the 1950s, as a unified nation composed of 55 ethnic minorities, each with its representative costume, in addition to the Han Chinese majority. This colorful diversity has been featured in earlier propaganda posters, though the government has become more restrictive in recent years in its presentation of China as a land of uniformity.

Shifting Boundaries

Since 1956, Yao people have been classified collectively as one of China’s 55 ethnic minorities (or minority nationalities), despite a great deal of linguistic and cultural diversity enveloped in one label. Identifying, labeling, and classifying China’s ethnic diversity, especially in border regions, was a long and difficult process that began well before the founding of the People’s Republic of China, and it was never written in stone that there would only be 55 ethnic minorities. As Thomas Mullaney describes in his book, Coming to Terms with the Nation: Ethnic Classification in Modern China, the team of linguists and anthropologists from the Ethnic Classification Project who were sent to Yunnan in the 1950s identified more than 100 different ethnic groupings at first, some with less than five people in that province alone.

In 2008, while traveling with local officials, who were themselves Yao, in the adjacent province of Guangxi, in an area where Yao, Han, and Zhuang lived in proximity to each other, I asked about the meaning of “Yao.” The response I received was: “Yao live in the mountains, Zhuang live by the water (rivers), Han live on the streets (in town).” This statement represented for me the fluidity of identity, especially in this border region. I asked the local officials, what happens if a Yao person moves into town or marries a Zhuang person, as some did?

This local 21st century understanding of Yao people matches the definitions I found in official histories and other Chinese sources going back to the 10th-13th centuries when the Yao were first mentioned in written accounts. In those sources, Yao people are always described as the peoples in the mountain valleys of Hunan, Guangxi, and Guangdong who lived beyond the boundaries established by the imperial court, and thus were not registered, tax-paying subjects.

Over time, imperial governments projected those administrative boundaries across an ever-widening territory in the south. Some people identified as Yao remained beyond those boundaries; others registered as imperial subjects and by the 20th century were recognized as Han Chinese. It was many centuries before the Yao were incorporated into the modern Chinese nation state, or they crossed borders to Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand, where they remained and became citizens of those countries. The story of the Yao people is also the story of how those borders came into being.

The story of the Yao people is also the story of how those borders came into being.

Everything Has a History

There is a poster from the American History Association hanging on the wall of the Department of History, deep in the corridors of Clark Hall: Everything Has a History. These words resonate with my understanding of the importance of the tools of historical research in contemporary society. History is not simply about understanding the past, though that is part of it, but also how the past lives on in the present and how the world we live in became the way it is.

“Everything has a history” applies equally to borders and to border people, among them, the Yao. From the earliest representations in Chinese historiography, the process of labeling diverse peoples as “Yao” was inextricably linked to the governmental act of claiming and visualizing territory: what and who counted as the imperial, and later, national realm. As local officials placed down their markers, those who remained apart were called “Yao,” which came to be an identifying border inscribed around numerous not entirely related peoples with different self-identities. Just as the border between China and Myanmar can be traced back to 1960 and a history of political conflict and treaty negotiation, there are also specific histories that explain how border peoples were written into the narratives of empire, which influenced how the nation-state was conceptualized in more recent centuries.

About the Author

Dr. Eli Alberts is an Associate Teaching Professor at Colorado State University. He teaches Chinese and East Asian history for the Department of History, Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, and the International Studies program. Dr. Alberts has published a book "A History of Daoism and the Yao People of South China" and contributed to several journals with his research on the Yao people.

Dr. Eli Alberts is an Associate Teaching Professor at Colorado State University. He teaches Chinese and East Asian history for the Department of History, Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, and the International Studies program. Dr. Alberts has published a book "A History of Daoism and the Yao People of South China" and contributed to several journals with his research on the Yao people.

Navigating Borders

From water to dance, science to film, clay to gender, the liberal arts helps us navigate the borders in our lives that are physical, metaphorical, or cultural.