The Rio Grande River Basin (RGB) is a non-renewable resource that supports millions of human beings and tens of millions of species. This is the story of an important river that often goes unnoticed, and the lives and systems that the river impacts.

Logging onto Google Maps in satellite view, place your cursor just east of Silverton, Colorado to find the headwaters of the Rio Grande River. If you zoom out just the right amount, you will see that the headwaters reside in the Weminuche Wilderness. Weminuche describes a small band of the Ute Native American tribe, who resided in Larimer County. In 1878, all members of the Ute tribe were forced out to reservations near the Weminuche Wilderness.

The preceding information is adapted from the report "People of the Poudre - Native Americans in Larimer County, Colorado: 12,000 y.a - 1878" by Lucy Burris.

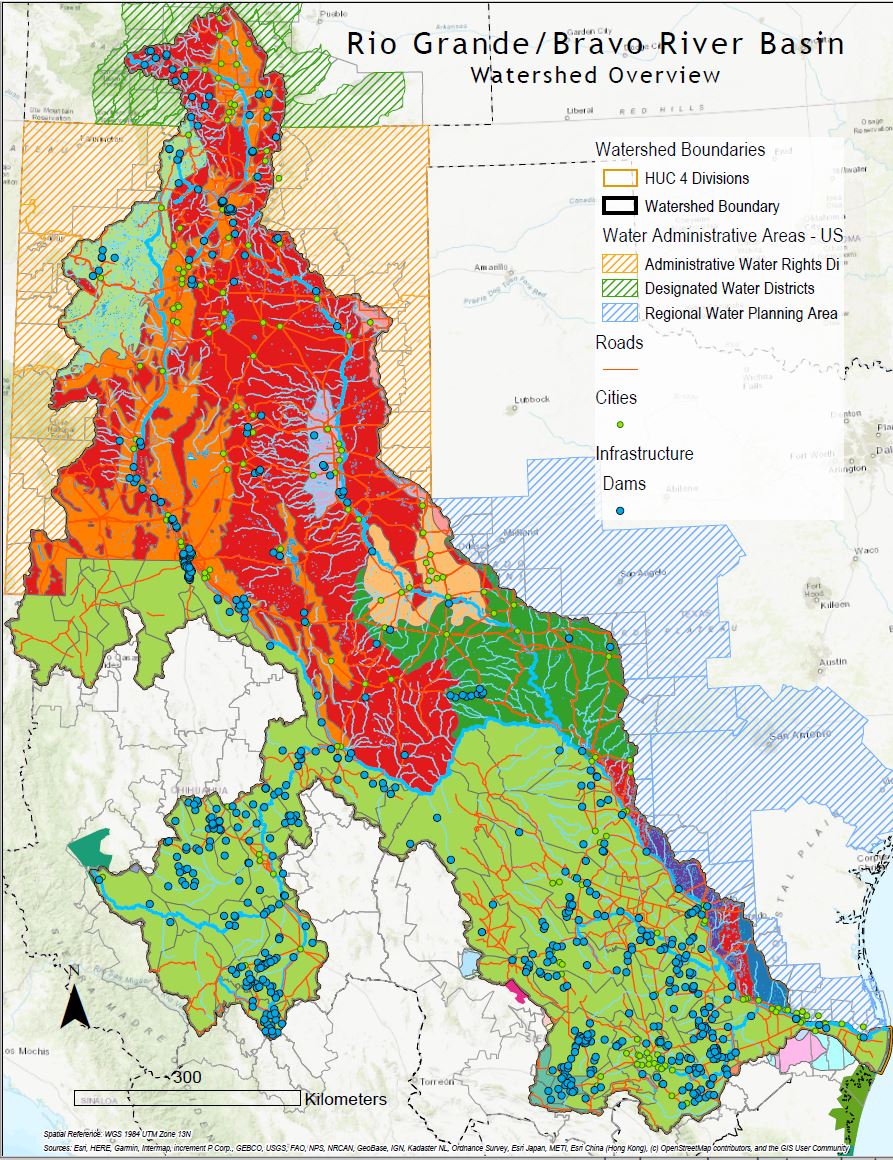

And so begins the flow of the Rio Grande River for the next 1,896 miles. Depending on how wide your lens, you will see the river winds through the San Juan Mountains of Southern Colorado, through New Mexico to the western border of Texas between the United States and four Mexican states—Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas—ultimately draining a total of 182,200 square miles of watershed.

A tighter zoom reveals the merging of the smaller creeks with names like “Fern” and “Willow,” and also features the sharp cuts of human-made ditches named “Excelsior” and “Chicago,” reservoirs with high dams, and sprawling cities such as Albuquerque and El Paso-Ciudad Juárez. A click out to a broader view unveils the persistence of the mighty river over dams, across deserts, and through hazardous waste sites and border walls until it joins the waters of the Gulf of Mexico just a few miles south of South Padre Island, Texas.

The diverse ecosystems of the Rio Grande basin include dozens of wildlife refuges and wilderness areas, and support agriculture that grows the famed Hatch green chiles and other staple crops including onions, potatoes, pumpkins, watermelons, lettuce, cabbage, corn, and beans. Oil and gas are extracted from underneath the basin, while above it, tourists and commercial fishermen depend on its resources. The Basin is home to 18 of the 19 Tribal Pueblos of New Mexico (with only the Zuni outside the region) and four additional Tribal nations. Municipal water demand is expected to increase by 100 percent in the next 50 years, and industrial water use will increase by 40 percent (IBWC).

“Water justice in the Rio Grande basin engages societal, economic, and political conditions at multiple scales, subnational, national, and binational. Along the U.S.-Mexico boundary, for instance, historic economic and resource asymmetries between the two countries shape both the realities and perceptions of inequality and injustice and how they are being addressed by governments and publics.”

– Professor Stephen Mumme

These physical and social characteristics are compounded by a changing climate, which has resulted in severely depleted waters, threats to biodiversity, and compromised health, especially among Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) residents in the Rio Grande Basin. These pressures set the context for an examination of competing demands for water through an environmental justice (EJ) lens. The research of the Rio Grande Basin Environmental Justice Research Team explored the intersectional EJ issues and opportunities for just transitions in a transboundary watershed. Researchers remain especially concerned with issues at the Food-Energy-Water nexus.

Rio Grande Basin Environmental Justice Research Team

Dr. Stephanie Malin

Dr. Melinda Laituri

Dr. Josh Sbicca

Kelsea MacIlroy, MS, ABD

Kathyrn Powlen, MS

Joshua Reyling

Dr. Stephen Mumme

Dr. Sybil Sharvelle

Illuminating Environmental Justice through Spatial Justice Tools

Foundational to understanding EJ issues in the RGB is spatial justice— the intersection of the environment and social justice that represents the consequential geography of places that reflect socio-political outcomes on the landscape. In order to understand the consequential geography of spatial justice, researchers from the University’s Center for Environmental Justice (CEJ) developed a geospatial inventory of EJ stakeholders across the Rio Grande Basin and created a geospatial database of the watershed.

Using these tools as an interactive map, researchers and members of the community are able to work together to identify common stakeholders (intentionally including BIPOC members), vulnerable populations, and mechanisms for creating democratic decisions about the RGB that are more inclusive and ecologically sustainable. For example, they can determine what crops should be prioritized to grow using water from the RGB; they can understand what invasive species pose the biggest threat to biodiversity in the area; and they can determine how urban growth impacts important agricultural areas.

The Role of Procedural Justice

Equally important to creating a stable and sustainable future for the Rio Grande River Basin and all of its inhabitants is the implementation of procedural justice and equitable decision-making: How are diverse voices included in determining what is studied, and in making decisions that affect their lives?

After Stephanie Malin and other CSU researchers conducted initial research and fieldwork, the Santo Domingo Pueblo convened the New Mexico Tribal Environmental Justice Roundtable. Cynthia Naha (director of the Natural Resources Department for the Santo Domingo Pueblo) and Sharon Hausam (planning program manager for the Laguna Pueblo and a research associate at the University of New Mexico) acted as the main organizers of the event which brought together 30 Pueblo/Tribal environmental professionals, who represented 10 of the 19 different Pueblos across New Mexico.

Roundtable discussions addressed issues related to complex dynamics of water, energy development, legacy contamination, and climate change, illuminating the importance of including a justice perspective in addressing these complex problems. These discussions revealed that important research and tools have already been developed within the affected communities, and people’s health is a deeply held concern across Pueblo and Tribal communities. Extensive community-based mapping of invasive species, including giant reed and tamarisk has already taken place in the RGB. Contamination around Los Alamos National Lab, oil and gas production throughout the state—and near sacred lands such as Chaco Canyon—as well as the ongoing impacts of open-pit uranium mining around the now-defunct Jackpile Mine, continue to impact the health of the communities.

Researchers confirmed that people’s concerns over water quality and water scarcity intersect with almost every other experience of environmental injustice discussed at the Roundtable. The Center for Environmental Justice at Colorado State University will continue to build space for collaborative, community-based, and interdisciplinary research, policy, and engagement to resolve issues of environmental justice and health.

The research team appreciates the Colorado Water Center’s support in initiating the relationships in both the New Mexico Tribal Environmental Justice Roundtable and the Geospatial Mapping projects. Other versions of this work can be found here.

Portions of this section have been published in Green Fire Times’ coverage of the Roundtable.

Navigating Borders

From water to dance, science to film, clay to gender, the liberal arts helps us navigate the borders in our lives that are physical, metaphorical, or cultural.