Are Americans really as polarized as we are told we are, or is this a misperception we hold?

A recent study by nonprofit More in Common titled The Perception Gap suggests that Americans are more similar to their political opponents than they realize. The findings from the study show the perception gap in American politics has created a deeply distorted understanding of each other.

The extreme political polarization in our country is rooted in our inability to separate perception from reality, labeled in the study as “The Perception Gap,” which greatly impacts our ability to communicate with each other. Even on the most controversial issues in our nation, Americans are much less divided than most of us think.

So, if we are less divided than we think, why are perceptions on the left and right so far apart?

Dominik Stecuła – an assistant professor of political science at Colorado State University who specializes in political communication, political behavior, social media, and polarization – believes there are numerous factors contributing to the divide.

Factor 1: Politically Homogenous Communities

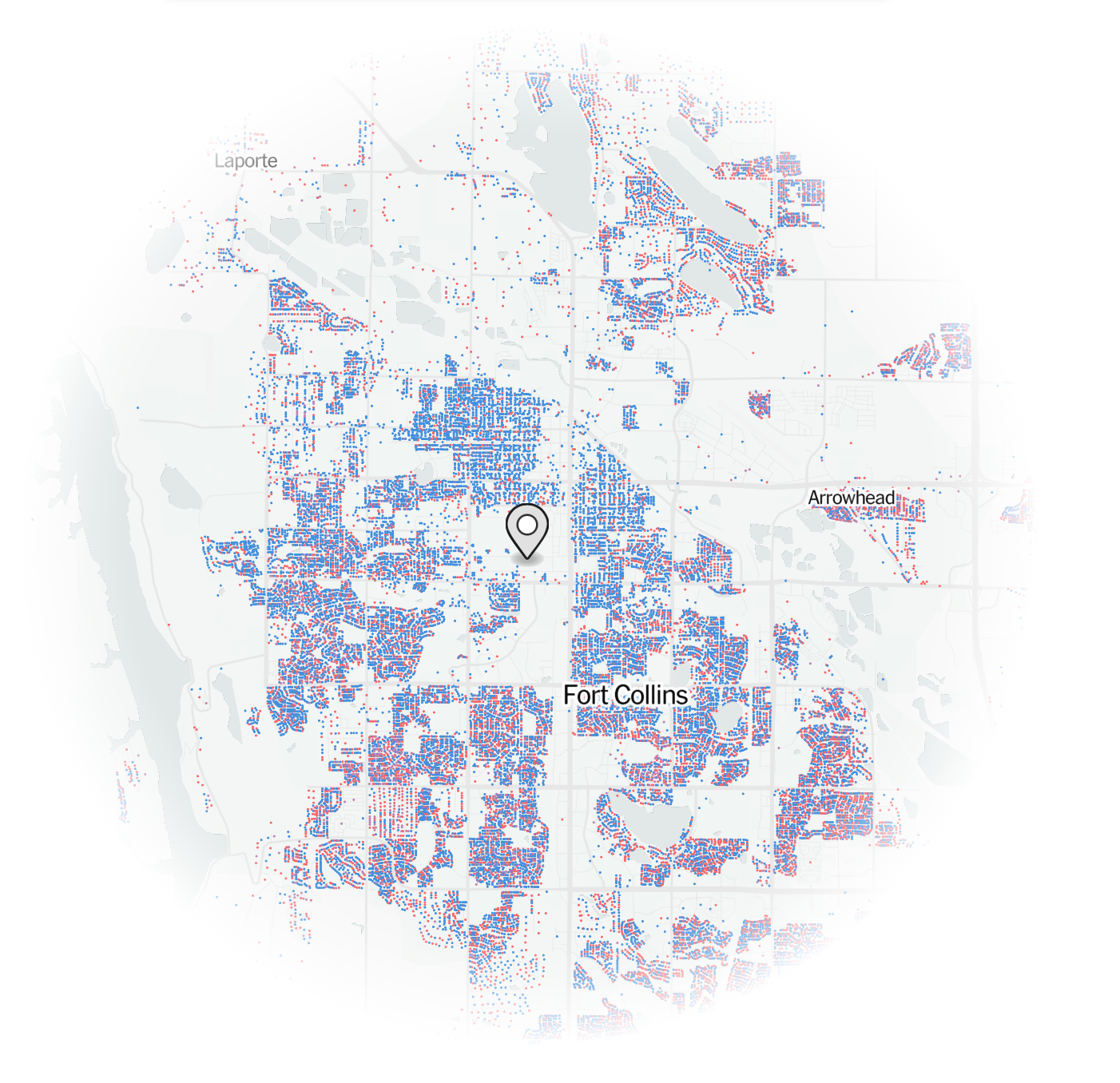

Stecuła points out that the places we live tend to be politically homogenous. “That impacts the yard signs you see, bumper stickers, random conversations with neighbors. In short, we have limited exposure to ‘the other side’ so where we get our cues about what the other side looks like is from the media, either traditional or social,” he says.

“Depictions of ‘the other side’ in the media and on social media are not accurate,” he continues, “these places bolster extremes, unhinged lunatics, and highlight those actors on the other side. So, when MSNBC talks about Republicans – they’re not really talking about Romney – they’re talking about Lauren Boebert, MTG, Matt Gaetz, etc.”

“Our mediated reality is full of extremists, rather than those who live in the middle, and so we are lead to believe these folks are prototypical members of the other side.”

Factor 2: Social Media

Social media is an important part of our daily life and undoubtedly plays a role in our political perceptions. But does social media expose us to different viewpoints or is it an echo chamber? Stecuła says the literature on echo chambers is mixed. “Most Americans are not in one. Part of the reason for that is that most Americans are not interested in politics enough to bother creating a political echo chamber on their social media. They care about celebrity gossip, sports, and other stuff much more,” he continues, “but echo chambers are very much a thing that the political elites are in. And that exacerbates our perception of polarization because political actors, journalists, commentators, people super into politics are in echo chambers, and live in a political bubble.”

If a majority of your news derives from social media, Stecuła suggests “you need to really work hard to curate a space that is informative and nuanced. A lot of people don’t have the time, or the knowledge of our media landscape to do that, so they just go with the flow, and in that case, information you encounter is very hit and miss.”

Factor 3: News Coverage

Media still plays a very important role in our democracy in keeping people informed — or at least more informed than they would be otherwise. “I’m a political science professor and I need the media because I won’t necessarily watch a congressional hearing on C-Span or provide some details about policy proposals,” Stecuła says.

He warns that not all “news media” is created equally. “Cable news is best to avoid. CNN can be good when they’re broadcasting from a war zone but are much less informative about day-to-day politics. They don’t have any incentives to generate coverage that is deep, thoughtful, and nuanced,” he says. He suggests that evening news broadcasts on CBS, NBC, ABC or PBS are much more informative, and national and regional newspapers are also reliable.

Factor 4: Political Segregation

Not everyone has the same background or experiences — which is often how our views are formed. Studies show that Americans are becoming increasingly alienated from our political opponents not only ideologically but geographically as well. This political segregation can lead to heightened animosity and feeling increasingly threatened by each other, causing a drop in civil discourse, more hateful public debates, and falling further into the depths of political polarization. It is important to recognize that disagreement and conflict are necessary components of a robust democracy. Talking to people with very different views allows us to escape from the political bubble most people find themselves in. Along with the conflict there needs to be a sense of shared values, and a willingness to find commonalities. “By understanding our Perception Gaps, working to overcome our mistrust of the other side, and resisting the forces that seek to divide us, we can advance towards a future that we all want,” advises More in Common.

In Stecuła’s co-authored book with Matt Levendusky, We Need to Talk, the authors show how having cross-partisan discussions with people can decrease polarization. While issues arise when persuading the general population to engage in these types of conversations, Stecuła believes that colleges and universities could play a major role in cultivating these cross-partisan discussions. “Fostering intellectual and political diversity and providing spaces where people with different beliefs and values interact in meaningful ways would be one concrete way to do this,” he says. Though many institutions of higher education lack conservative voices on campus, Stecuła does not see that issue at Colorado State University. “While this approach might not work in a small college like Oberlin, where it’s essentially a progressive bubble, we could make [this approach] work at CSU,” he says.