“Health is a set of beliefs, informed by medical, social, and religious ideas, about what the appropriate use of the body is and the appropriate state of the body. These ideas are distributed across different social contexts” – John Slater, associate professor, Spanish

In the U.S. today, we have a variety of choices to make about our health: Fresh vs pre-packaged foods. Vegetarian, vegan, keto or paleo lifestyles. Supplements for sleep, inflammation, or mineral support. Walking vs cross-fit. Fasting. Aromatherapy. Acupuncture. CBD oil. Pills. Surgery.

Depending on the region of the country, your religion or political persuasion, your peers, your media sources, or your belief in the medical industry, specific notions of health vary. That is, until new information comes out that debunks that previous philosophy about wellness and shows us something new.

“Arriving at a consensus of how to define health is a wicked problem,” says John Slater, associate professor of Spanish. Whether it’s 500 years ago or 5 years ago, “we have consistently failed to agree upon a definition of what it means to live a healthy life.”

Slater studies the history of science, the history of medicine, and early modern Hispanic literature in the early modern Spanish empire (1580-1680). Specifically, he focuses on chemistry and chemical medicine (often indistinguishable from alchemy at that time) and the ways in which preachers, monks and friars disseminated new ideas about chemistry and chemical medicines.

“Our ideas about what health is and what sickness and disease mean are big questions about what kind of society we want to live in, what it means to have a good life, and what it means to be living as you believe is most appropriate or best,” says Slater.

Health & Medicine in the Early Modern Empire

A lot of ideas about medicine in Spain were shared with the world of ancient Greece (Hippocrates) and the Islamic world. “Classic medical texts had a long tradition in medieval Spain through Arabic commentary: there were commentaries on Greek and Roman texts in Arabic translation by Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina that were then translated into Latin and vernacular languages,” says Slater. “Authors of medical texts, such as Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi, were familiar to nearly all European physicians during the Medieval and Renaissance periods.” (13th c to 17th c)

This tradition of translation and commentary among several languages and peoples helped to consolidate ideas across the Mediterranean about health practices and physiology.

For hundreds of years, bringing about balance was the central idea across Europe. “Having your body in balance – including diet, sleep, exercise, sexual activity, and dreaming – was important. And health was defined as balance,” says Slater.

In the late 1400s, a few things happened culturally and politically to start to change the medical landscape. “With the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492, that dealt a blow to the healthcare apparatus, and they needed to recruit new people into the healthcare profession,” says Slater.

"Health was defined as balance."

Also in the late 1400s, Muslims in Spain were forced to convert to Christianity. In some places, the converted Muslims were 1/3 of the population (such as in Valencia). Physicians at the time recognized the Muslim traditions of herbs and how to use plants as useful. “From region to region, and group to group, there were different health practices and knowledge about plants that were incorporated into the way medicine was practiced,” says Slater.

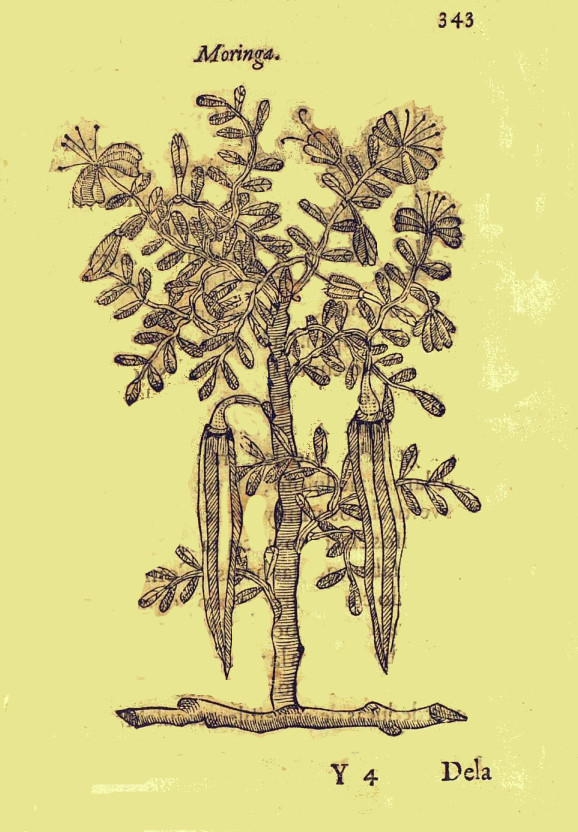

At the same time, Spanish soldiers, missionaries, and emigrants traveled to other regions around the world, bringing their own ideas about sickness and health. In turn, their ideas were influenced by indigenous medical cultures they came into contact with. “American medicinal plants, such as guaiacum, tobacco, and palo santo were quickly incorporated into European pharmacopeia. By the middle of the sixteenth century, Iberian authors such as Garcia de Orta and Cristóbal Acosta had written important books about the medicinal plants of Spain and Portugal's colonies,” says Slater.

As populations changed, and declined catastrophically in the colonies, these new practices, which were geographic and culture dependent, were studied and adopted. The shape of healthcare in Spain began to change.

The Catholic Church Takes A Prominent Role

A common strategy that physicians at the time used for achieving much-desired balance was bleeding and cauterizing. The idea was to remove “bad humors” by draining them out of the body, which was a painful process.

By the 17th century, with the removal of many Jewish people (physicians) and adoption of new and different medicinal practices by colonized regions, the Catholic church, which had maintained a focus on taking care of the soul, saw an opportunity to take care of the body, which had been strictly the realm of the physician. Churches started to take interest in the most modern form of medicine – using distilled medicine, such as brandy – rather than bleeding to dissolve “poor humors.”

Brandy as Medicine

Some of the best known in the US are French: Chartreuse—made by Carthusian monks—and Bénédictine—made by Benedictine monks; both of these religious orders we also active in Spain where they produced distilled medicines

“A priest will visit a patient after the physician has declared there is no saving the patient. The priest will come in with a salve and a spirit of wine – and those forms of less drastic intervention were better or at least less harmful. No more bleeding!,” says Slater.

Because this approach was less painful than other strategies, this move “allowed church leaders to take on a new role in taking care of both the poor (which they were already doing) and the illustrious. It allowed them access to status and responsibility they had not had before,” says Slater.

In addition to this different way of approaching medicine and healing, the Catholic church focused on the theological drama involved in getting back to a state of healthful balance.

Slater describes it:

“The world follows a rhythm of God the poet. God speaks the world into creation, and through a rhythmic set of utterances creates the world. That rhythmic voice also describes the chemical processes of the earth such as the water cycle. The entire world, including human bodies, resonates to the rhythm of the initial poem that created the universe. Human beings imagine a kind of drama (the poem), and if through our medical practice we can repeat that rhythm, we will be healthier.

This is an idea that started in the Book of Genesis. And it was a new conception of what it means to think of our health as related to the creation of the world. Health interventions by religious figures may follow that divine directive.”

With the new knowledge of medicinal options from the Spanish colonies, the expulsion or conversion of different religious communities in Spain, and the integration of physical and spiritual health by priests assisting with both, the practice of medicine was transformed.

Whether we’re talking about today or the early modern Spanish empire, “people want access to healthcare and people don’t like it when medicine is really painful,” says Slater.

Our human tendency is to seek out new and different ways of achieving a state of health and incorporating a variety of (less painful) medical practices to get us there.

More Reading

John Slater is co-author of a collection of essays about medical cultures in the early modern Spanish empire. From literary anthropology to childbirth and its perils, astrological medicine to chemical medicine, this book covers a wide range of ideas and practices of people in the Spanish empire from 1460 to 1680.

Early modern Spain was a global empire in which a startling variety of medical cultures came into contact, and occasionally conflict, with one another. Spanish soldiers, ambassadors, missionaries, sailors, and emigrants of all sorts carried with them to the farthest reaches of the monarchy their own ideas about sickness and health. These ideas were, in turn, influenced by local cultures. This volume tells the story of encounters among medical cultures in the early modern Spanish empire. – an overview of Medical Cultures of the Early Modern Spanish Empire, by John Slater, José Pardo-Tomás, Maríaluz López-Terrada (2014, Routledge Publishing)