How the Department of English moves forward in the wake of COVID-19

Cookie Egret is a Department of English graduate teaching assistant and Writing Center consultant. In the fall, she noted a steep increase in the number of students whose personal lives have been upended by the virus, which has increasingly consumed their academic focus.

“The focus of my composition class, CO150, is a researched argument,” Egret (MA ’21, Writing, Rhetoric, Social Change) said. “At least half of my students this semester are researching some aspect of mental health, whether it’s their own condition, medication uses or misuses, alternative therapies, suicide prevention, school accountability, mental health in media, and on and on.”

Students during one-on-one sessions, now held online, tend to downplay emotional stresses, but she notes common themes in the pressures they experience, especially surrounding relationships.

“They’re not getting the college experience they expected because they can’t socialize in the way they expected,” she said. “Responses from new students especially have been along the lines of ‘it could be worse, but I wish I had some friends.’

It’s hard to hear.”

At the same time, Egret is questioning her ability to help her students as she deals with the pressures of her own job and coursework — writing a master’s thesis ahead of graduation during a pandemic.

Initiatives that seek to bolster mental health, such as reading, writing, and thinking reflectively, creatively, and critically have long played an important role among students and the broader community.

In the Department of English at Colorado State University, initiatives that seek to bolster mental health, such as reading, writing, and thinking reflectively, creatively, and critically have long played an important role among students and the broader community.

English faculty consider the roles of established systems like work and school, and evaluate how these systems can both alleviate and exacerbate pressures that weigh upon the mind.

Courses in the department challenge students to think critically about the nature of mental health and the ability of creative writing and reading literature to play therapeutic roles in addressing mental health.

Faculty-led responses to these issues have included reaching local communities through the University Writing Center and participation in programs like the Veterans Writing Workshop for military members and Speak Out!, which reaches incarcerated persons in Larimer County with opportunities to publish works of creative writing.

Emotional labor

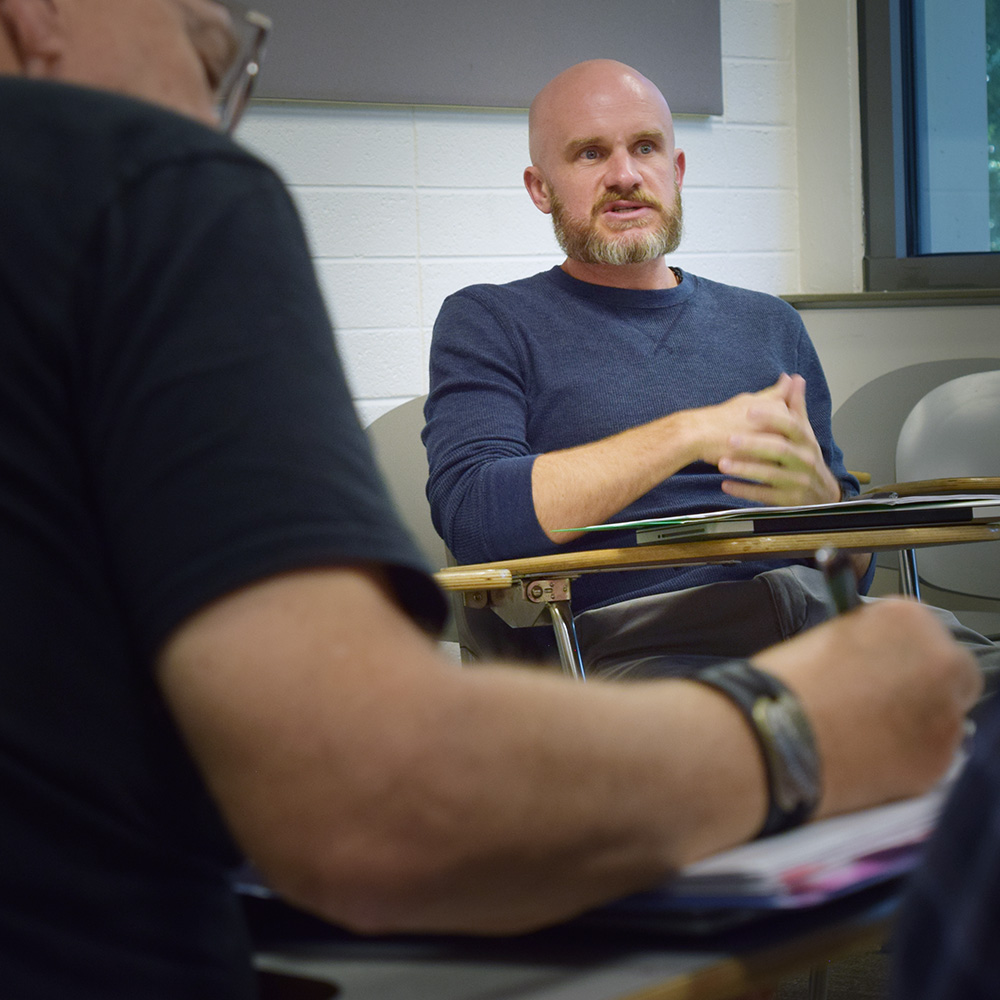

In the University Writing Center, part of the English department and the College of Liberal Arts, CSU students and the Fort Collins community can take advantage of free consultation on any work of writing, at any point in the writing process. Participants typically work with a single Writing Center consultant — usually a CSU graduate student — over several sessions.

“They build a relationship,” said Associate Professor Lisa Langstraat, director of the Writing Center. “Students who are speaking with us regularly get to know specific consultants, and they tell us what they’re going through.”

Feelings of mounting pressure among faculty and students like Egret have also been the focus of a class taught by Langstraat on critical emotion study, namely on emotional labor — those emotions required by work, school, and other social systems, which are not listed as associated responsibilities.

“As we’ve moved into more of a service sector, where we don’t produce as many goods, more and more jobs generally are founded on emotional labor,” Langstraat said. She pointed out that this has always been a factor in teaching, where instructors assume responsibility for many of the affective needs of students.

Now, on the heels of COVID-19, she said, “Faculty are experiencing the demands of emotional labor in ways they never have before, and we really haven’t been prepared as teachers to handle our own affective needs.”

Still, faculty responsibilities and related emotional labor extend beyond the classroom and into the community outside CSU. Programs that serve as an outlet for people experiencing mental health issues have also been hamstrung by mandated social distancing.

Reaching out

Since 2005, the English department’s Speak Out! program, part of CSU’s Community Literacy Center, has reached incarcerated people in Larimer County with in-person opportunities to participate in the creative writing initiative and to have their work published in a twice-yearly journal.

Seven SpeakOut! writing workshops at four community partner sites across the county use the weekly sessions as “opportunities to understand their own lives, to make their voices heard, and join a community of writers committed to exploring the ways that words shape and influence our lives,” said Professor Tobi Jacobi, director of the Community Literacy Center.

Speak Out! is committed to understanding how literacy contributes to wellness; the program regularly incorporates self-care strategies into facilitator training sessions and has partnered with Denver's Center for Journal Therapy to learn techniques for using writing to support mental health.

“Over the past 15 years feedback from participants has been consistent,” Jacobi said. “The community writers we work with can't wait to get in the room and starting composing. Writing with a SpeakOut! group offers them a lifeline to others experiencing similar challenges and methods for understanding the value of their life stories - and then they get a chance to put them into the world through the SpeakOut! Journal.”

Back on campus at CSU, the Veterans Writing Workshop, offered by the English department and Writing Center, welcomes military veterans, active members and affiliates to submit works of creative writing for publication in the journal Charlie Mike — a military designation for the letters “C” and “M” representing “continue mission.”

The program’s organizer and U.S. Army veteran Ryan Lanham (MFA '21, Creative Writing) says the term Charlie Mike is a call to action to carry on in the face of emotional and mental pressures of military life and experience.

Workshop members over the last year have described the healing effects of the workshop. In a previous interview, U.S. Army veteran and CSU Health Network therapist Mark Cunningham (MS '18, Human Development and Family Studies) said personal interactions during sessions helped “give power” to his own voice.

“I’m not serving as a therapist here, but it feels like there’s therapy going on in terms of just the natural, organic process that unfolds as people pour their hearts out,” he said. “Getting to read your writing and getting your chance to have them [workshop participants] reflect back what it meant to them has been very healing.”

Programming during a pandemic

With the onset of COVID-19, these programs, like others across the university, have seen a stark decline in participation and limitations of their reach. Many students and community members who enjoyed in-person access to mentorship in a distraction-free setting have seen it moved online as pressures increase from quickly changing dynamics at home and among social circles.

Many programs across CSU and at universities across the U.S. have rushed to adapt. Consultant groups in the Writing Center, for example, are now using online teaching modules to help students through writers block.

Speak Out! continues to operate through synchronous meetings among youths via Google Hangouts, and the program reaches its jail populations twice monthly with video prompts and writing materials.

“We’ve made significant changes,” Jacobi said, “but of course it’s not the experience that students and writers expected.”

The Veterans Writing Workshop, meanwhile, is on a scheduled hiatus, and Lanham will pass the program on to a new leader when he graduates in May. Still, he considers what will become of the sessions when the program returns.

“Most of our members are Vietnam vets,” Lanham said. “They’re in their 70s, 80s, even 90s, and none of them want to be taking risks with their health.”

Systemic solutions and challenges

While helpful to many who access them, programs designed to improve mental health can bring their own set of issues if they assume that healing should come from within the mind, said Erika Szymanski, assistant professor of rhetoric and composition.

Szymanski points out that physical pressures like stress, disease and isolation materially affect “who” people become in many respects, including as reading and writing bodies. These external or environmental effects occur beyond the control of the individual, which makes finding a wellness solution difficult, if unlikely, within the affected mind.

She uses writing and mindfulness exercises as examples of practices that can inadvertently place the responsibility of mental health on the individual by seeking solutions separated from environmental causes of the problem.

“The problem is beyond you,” she said. “As creative people, we like to think we can write our way out or correct it ourselves, but admitting that the problem is environmental is important.”

Szymanski also points out that this dynamic cannot be attributed to any person or institution, but rather, is a result of historic work and learning system structures.

“A materialist and posthumanist lens on mental health might note that contemporary sciences and modern society have been teaching us for more than a century to separate information and material,” she said.

“As creative people, we like to think we can write our way out or correct it ourselves, but admitting that the problem is environmental is important.”

“None of this is to say that people shouldn’t use reading and writing to think about and to cope with tough times,” she said. “I’m doing plenty of that myself right now!

“But, if we commit to moving away from trying to assess people on reflection or meta-cognition – what goes on inside their heads – and we move toward their capacities to be relationally effective – what they do to be responsible and effective participants in composing networks – then we also need to move away from the idea that individuals can or should use reflection to take responsibility for their own problems when those problems do not belong to them, but are a product of their circumstances.”

The longstanding wicked problem of mental health has reemerged as a societal focal point in the wake of COVID-19. The looming threat of illness and related mandates for sheltering in place have been sources of major disruption, causing students, faculty and staff to suddenly and drastically reevaluate and rebalance the dynamics of school, home, and work.

The individual and collective processes of reading, writing, and thinking that occurs in English courses and programs – in classrooms, workshops, and online – can provide the therapeutic means to navigate our own sense of who we are and what challenges we face as well as understand how our present circumstances are contributing to our well being.