Photo: Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Connecticut

How does our examination of the archives of early American literature create positive change today?

It’s a question Peter Wilson, a Blake Leadership Scholar and senior studying English and philosophy in the College of Liberal Arts, has considered deeply while completing his internship this past summer under the guidance of his mentor, Professor Zach Hutchins.

While taking Hutchins’ graduate course on the work of American novelist Gloria Naylor in the spring of 2022, an enthusiastic Wilson reached out to his mentor to see what internship possibilities existed for him – as someone eager to pursue a future academic career focused on early American and African American literature.

“As a hopeful future PhD candidate in English, I knew that to be competitive I needed to find an internship that spoke to my passion,” Wilson said. “Since the murder of George Floyd, I’ve been engaged in working on my internal knowledge of the ways in which systemic racism and oppression show up in our past and present, and wanted to deepen my understanding of how these systems are reflected in our history and perpetuated through modernity.”

Professor Hutchins introduced Wilson to his latest book project: As one of the editors of a new edition of A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (part of a planned volume of anti-slavery writings from Oxford University Press’ forthcoming Collected Works of Harriet Beecher Stowe), Hutchins was looking for a fact-checker to verify and track down sources published more than 160 years ago.

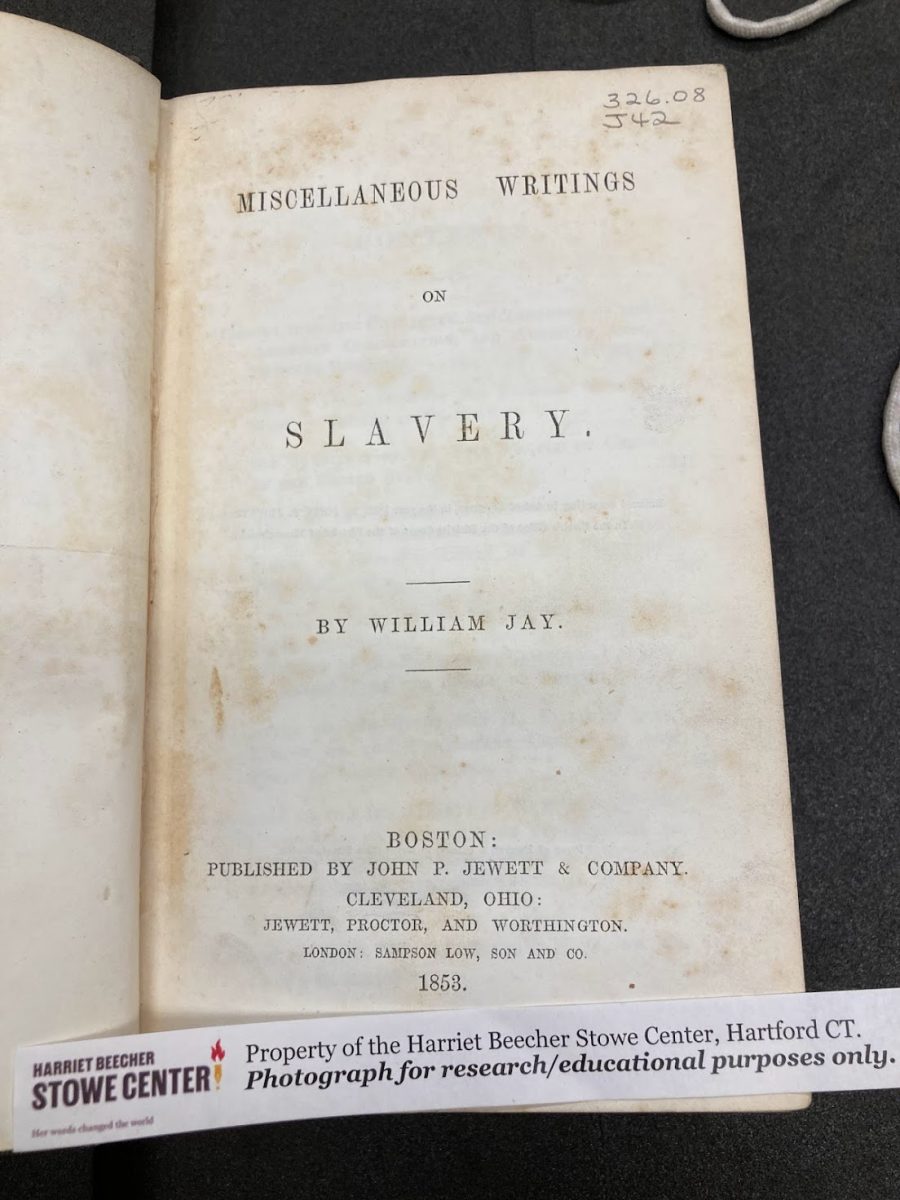

The internship – a six-month exploration of all the material cited in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, an ancillary work of nonfiction meant to corroborate the events of the famous anti-slavery novel, involved digging through the digital archives at CSU’s Morgan Library to locate quotes, anecdotes, and documents mentioned in A Key to authenticate their accuracy and existence – and culminated in a trip to Hartford, Connecticut this past July to find some of the original sources in person at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

Hutchins received funding through the Department of English to hire Wilson to work on the project and track down original manuscripts, which included church writings, printed newspaper advertisements, and legal briefs from before 1852. Fascinated by the scale of information in the Stowe Archive, Wilson discovered texts he never knew existed. “I’ve never worked in an archive before, and it was so interesting to be a part of the recovery process of lost knowledge and see how extensive the system is and how many materials there truly are.”

Ultimately, Wilson was particularly drawn to the physical nature of his fact-checking mission: of making the journey to Hartford to see the original letters and pamphlets behind glass, preserved for nearly two centuries. Here, he observed that “while the popular and famous voices of the past are available online, the voices of the commoners, those who historically lived mundane lives, still exist on paper. If you want a real picture of America’s past, where the maximum number of perspectives are considered, then you must return to the physical world.”

What a new edition means now

While very little scholarship exists about A Key as a literary text, Hutchins is excited to see how this edition will spark renewed conversation and interest about the book’s historical influence.

“A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin foregrounds the ways in which fiction was enmeshed in and sprang from popular discourse and print forms, such as the newspaper—which is where the voices of enslaved individuals were more frequently recorded, in the early nineteenth century, rather than bound in books,” he said. “Furthermore, it will document the reading practices and source materials of abolitionists in a way that few, if any, other volumes have.”

Though originally published in 1853, Hutchins noted the relevance of a new edition of A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin in today’s political landscape couldn’t be plainer: “Given the resistance experienced by many to teaching about the history of race and slavery, it seems fair, to me, to say that there is still a critical divide in this country about whether and how to acknowledge the testimony of racialized people as they bear witness to the national sins of the United States.”

Wilson added that remembrance and recognition, while small acts of justice, are essential pieces to understanding the larger context of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s work and its contradictions. As a white woman writing about the atrocities of slavery for a Christian audience, Stowe’s story was widely available, and according to the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, “a runaway best-seller, selling 10,000 copies in the United States in its first week.” Less accessible Black voices, like the abolitionist Josiah Henson, whose autobiography The Life of Josiah Henson: Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself heavily influenced Stowe’s Uncle Tom character, did not receive comparable readership.

"That’s an essential piece of the conversation – how to engage Black story and scholarship from that time and give these voices clear and thoughtful attention,"

“That’s an essential piece of the conversation – how to engage Black story and scholarship from that time and give these voices clear and thoughtful attention,” Wilson said. “Looking toward grad school and reflecting on the work I’ve done with Professor Hutchins on the Key and in his literature courses, I’ve found that I want to pursue scholarship that specifically engages Black experience by those who hold that identity.”

As a mentor, Hutchins couldn’t be prouder of the work Wilson completed during his time at CSU. “As I’ve come to know Peter in a variety of settings, as a student, Blake Leadership Scholar, research assistant, and teaching assistant, I’ve consistently been impressed by his commitment to the welfare of all he interacts with. He genuinely wants those around him to succeed, and I think he’s acutely aware of the ways in which institutions and systemic forces have led racialized communities to suffer economically, politically, and socially.”

Not only has the internship deepened Wilson’s perspective on race, class, and authorship, it has also expanded his view of the literary publishing world, and the critical work that goes into editing a book of this historic magnitude.

“Before the internship, I was unaware of how much work is required to republish an edition of a book, especially a book from an author as well-known as Harriet Beecher Stowe,” Wilson said. “Editors not only need to choose which manuscript to base their edition off of, but also find differences between manuscripts, track down references made by the author, and then style the author’s writing to match their editorial vision.”

Ultimately, Hutchins and Wilson hope that when the new edition arrives in print, it will unlock fresh critical thinking surrounding the history and complexities of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

“Harriet Beecher Stowe recognized injustice in systems of slavery and oppression, and she published the Key to help combat that injustice,” Hutchins said. “I think Peter and I would both like to believe that the work we’re undertaking with the Key today might contribute, if only in some small way, to the creation of a more just, equitable, and diverse society.”