Imagined in science fiction books, TV, and movies, no one is a stranger to the concept of immersive virtual worlds. From Star Trek: The Next Generation’s holodeck to Neo learning kung-fu in the culture-defining film The Matrix, characters navigating a programmed reality, obtaining new knowledge and skills, and having tangible experiences is a well-trodden concept.

Access to virtual worlds is no longer a far-fetched concept. You can walk into a Best Buy or a Game Stop and choose from a variety of VR headsets and find yourself completely enveloped in a different reality as soon as you get home.

“I love the full immersion of a VR headset – I love being enveloped in the experience,” says Cyane Tornatzky, associate professor of Electronic Art. “As someone who engages the world in perhaps a porous way, the immersive experience allows for a calm focus. From training, to drawing to experiencing the art of others, when I’m in that space I feel that I can really pay attention and investigate.”

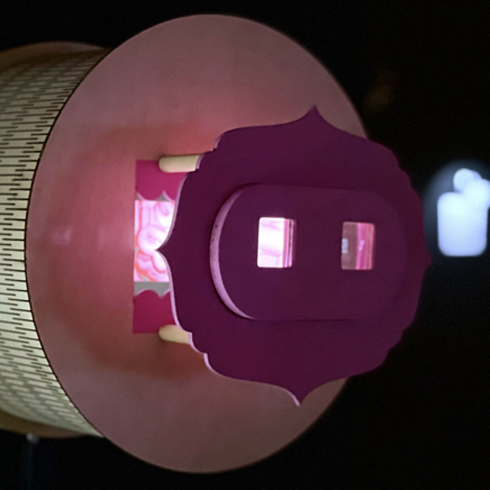

Intended to envelope the user in an interactive, audiovisual experience, a virtual reality headset is comprised of a display screen, movement sensors, stereo speakers, and a controller. The headset shields the participant from seeing or experiencing the physical world, replacing it with content projected on the display screen and the sound in the speakers.

The display screen projects two images, one for each eye, through stereoscopic lenses, similar to how the human eyes perceives visual information in the physical world. The images move in response to the movement data that is being processed and interpreted by the sensors in the headset, creating a 360-degree experience. The stereo speakers provide sound that mimics the way humans perceive distance and space through layering and 360-degree audio technology. The controller functions as the link between physical world and the virtual world by allowing the user to interact with the virtual environment the same way they would with the physical world.

I think about immersion and interactivity much more than in terms of ‘perception’. I think that as an artist, it is almost a foregone conclusion that art is about perception – a way of understanding or interpreting the world around us.”

Tornatzky has been working with various forms of interactive media such as experimental animation, digital printing, installation and video as her artmaking practice. “I think about immersion and interactivity much more than in terms of ‘perception’. I think that as an artist, it is almost a foregone conclusion that art is about perception – a way of understanding or interpreting the world around us,” says Tornatzky. “What intrigues me about virtual reality is setting up a scenario for a participant/viewer that invites them to explore an explicitly controlled environment. This can be in terms of artistic exploration, or one of digital simulacra. Is there something that a 360-degree field of view offers that can bring something new to our understanding of ourselves? What does that invoke for the viewer? How can we explore in a way that allows for participants to respond and react?”

Tornatzky’s interest in electronic art and virtual worlds began when she was working as a web designer in the early 2000s and found folks doing fun, weird stuff with code. “The internet of yore was much more open and free, and while there were business entities trying build a presence, it was a space for experimentation,” says Tornatzky. Ultimately, she stopped doing web design for clients and went back to school, learning that some of the digital explorers she admired had studied their medium.

After a post-bacc program and an MFA in Conceptual/Information Arts at San Francisco State University, Tornatzky found a medium that allowed her to explore concepts of dis-/un-covering both positive and negative aspects of our digital existence.

“My personal area of focus is interactive media, with a foundation in code,” says Tornatzky. “In almost all cases I am using some form of code to generate or modify content. The code can interact with visuals I’ve created, or it can create patterns that I then print. I’ve found that code allows me to explore what you might call “right-brain” thinking, while my “left-brain" artistic side also finds a venue for expression.”

The immersive experience VR offers can provide access to otherwise unreachable or risky experiences, and combined with what Tornatzy calls serious games, VR can provide a rich environment for training in the physical world.

“Video games as a form of entertainment have broadened to include a wide audience – in addition to the shooter games that people often associate with video games, contemporary gaming can also be slow, thoughtful and ask profound questions,” says Tornatzy. “Video games as an art form, sometimes called serious games, uses the structure of the game format to confound expectations, speak metaphorically about larger issues, explore and experiment.”

Tornatzky’s experience with serious games and VR as an artform gave her a unique in for a recently launched project called VetVR. Created by an interdisciplinary team, VetVR is a virtual module for training veterinary students in anesthesiology basics. By giving students the experience of real-world challenges in both the classroom and clinical rotations, VR can become part of modern education tools that simulate the cognitive and manual skills needed to navigate complex situations across many disciplines.

The VetVR team tested the tool by recruiting students to voluntarily take an anesthesiology exam both in a virtual setting and in a traditional classroom. By comparing their performances on the two types of exams, the team found that VR increased cognitive load but that could be explained by the newness of the experience. 70% of participating students had not used any sort of VR technology prior to the exam. While it’s a little early to tell what that means over the long term, the team feels confident that VR could eliminate the subjectivity of a professor and provide more consistency in the exam process. This year, the team will continue to explore the impact of VR education for veterinary students by training the students in the anesthesia VR module and then examining them with a real machine.

“My favorite thing about working on the veterinary simulator is working together as a team,” says Tornatzky. “We’ve been able to hire five of my current and former electronic art students to research and build the application, and I’m proud to have been part of their educational journey. In terms of my own work, it has been a reminder of how much I enjoy collaborating, and how much collaboration is a part of new media artwork.”

In a move to increase the accessibility of VetVR, the simulator was launched on Steam, a digital distribution service and storefront by Valve. Steam is the largest digital distribution network for PC gaming, with more than 132 million monthly active users. This size of an audience provides a great deal of access to virtual experiences like VetVR and can reach new and unexpected audiences.

Given that VR has the ability to recreate high-stakes situations with a lower-stake outcome, it is a promising way to train not just future veterinarians but other professions. VR provides a repeatability that is impossible to have in real life, which means a student could practice the scenarios over and over again. This potentially could create a situation much like Neo’s kung-fu experience - what one learns in a virtual world is repeatable in the physical world.

“Technology is so much a part of our lives that I don’t think we can define ourselves as separate,” says Tornatzsky. “Our perception of the world is very much affected by our contact with others through our phones, the internet. Technological mediation is an essential part of our contemporary lived experience.”