Prison agriculture programs may sound simple enough, and perhaps they’re even beneficial when they train incarcerated people in a skill and provide food to local food pantries.

But simple and beneficial is a mask. States and prisons profit when they receive funding for prison agriculture programs. Most programs pay workers less than two dollars per hour. These incarcerated workers do not necessarily receive training nor safety equipment, and even if they do re-enter society uninjured and with some new skills, they are unlikely to be able to earn a living wage. Such realities contribute to another interpretation of prison agriculture: being forced to work behind bars is exploitative.

The U.S. prison agriculture system has many layers, and social scientists Dr. Joshua Sbicca, Associate Professor of Sociology, and Dr. Carrie Chennault, Assistant Professor of Geography, are peeling them back. Together they have launched the Prison Agriculture Lab as a hub for not only collecting and analyzing data, but for translating academic and field research into easily accessible images, maps, data visualizations, teaching modules, and resources for students, researchers, activists, journalists, and anyone committed to advancing a more equitable society.

“This project began from the premise that a lot of the prison system is quite hidden, and the practice of prison agriculture is fairly hidden, despite the fact that agriculture has been really fundamental to the development of prisons, historically speaking,” explains Sbicca. “Agriculture has also been really important to maintaining prisons in the form of subsidies – food helps feed incarcerated folks but also produces profits that then are used to subsidize the cost of incarceration.”

When Sbicca first began to study prison agriculture in 2019 as a CSU SoGES Resident Faculty Fellow, he found only one national datapoint has been available for many decades. The Bureau of Justice Statistics asks one question in its occasional census about prison work requirements, which has one option to check for farming/agriculture. “That doesn’t really tell us much, so I started this project because I wanted to know so much more. Why do these practices exist? Where? What kinds of agriculture? The impetus was to shed light on what’s really going on,” he says.

With more than 1,100 adult-state run prisons in the U.S., Sbicca quickly realized collaboration would be necessary. Chennault, then a post-doc, came on board. Now an assistant professor, she and Sbicca received a 2022 College of Liberal Arts Ann Gill Faculty Development Award for Collaborative Projects to pursue this research.

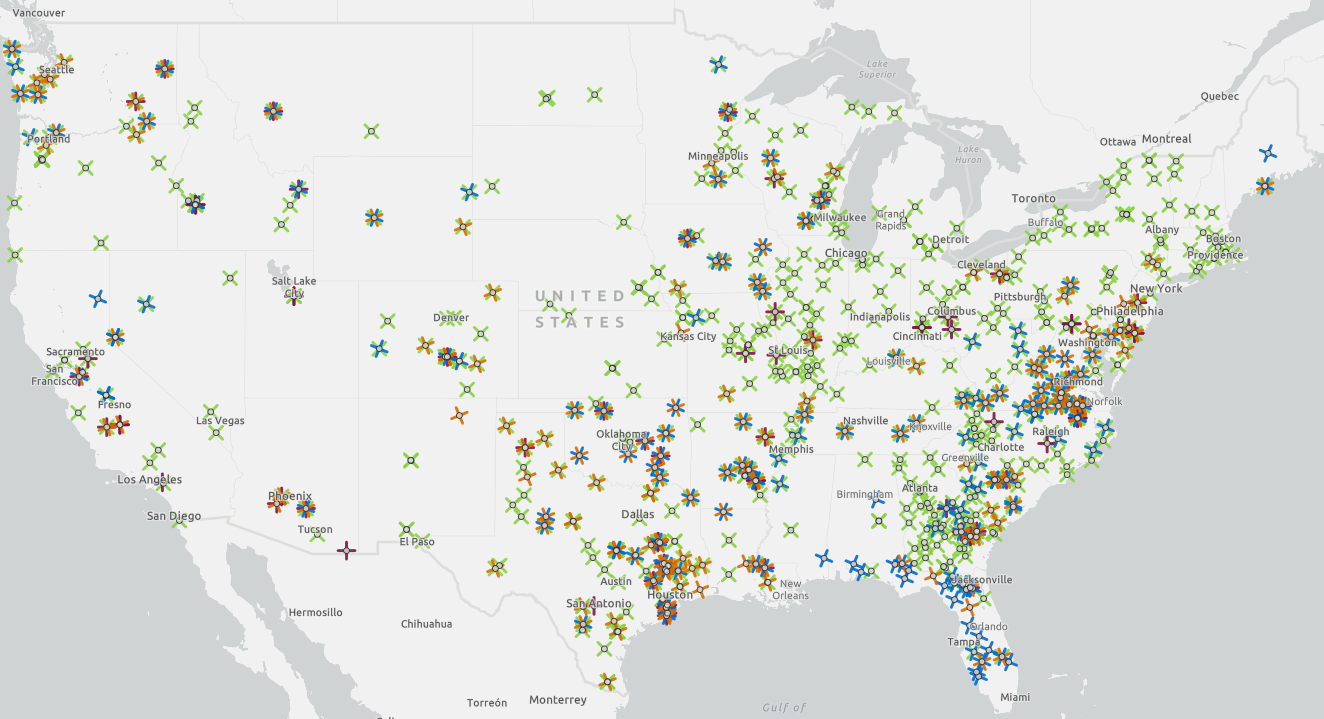

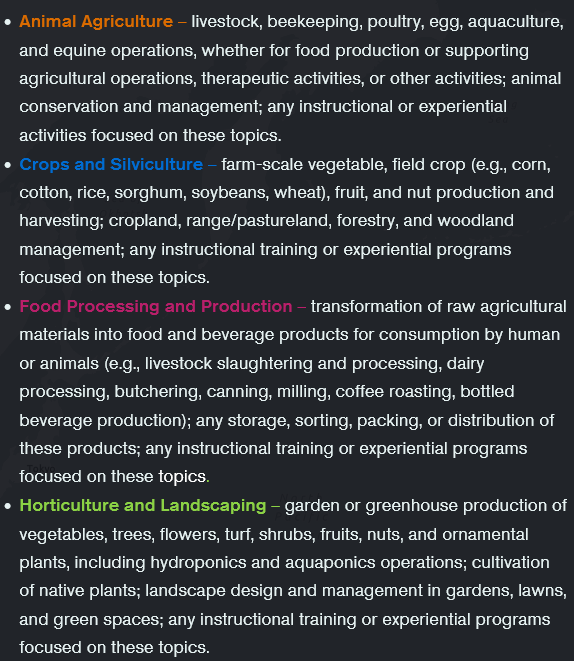

With the help of several CSU students and CSU’s Geospatial Centroid, the Prison Agriculture Lab recently released the nation’s first-of-its-kind dataset tracking prison agriculture. Spanning all 50 states, at least 662 adult state prisons have some kind of agricultural program (e.g. animals, crops, food processing, horticulture). The reason varies, but most commonly includes some combination of idleness reduction, financial gain, or training. This complexity has pushed the Prison Agriculture Lab to ask more critical questions about who is advantaged from these arrangements.

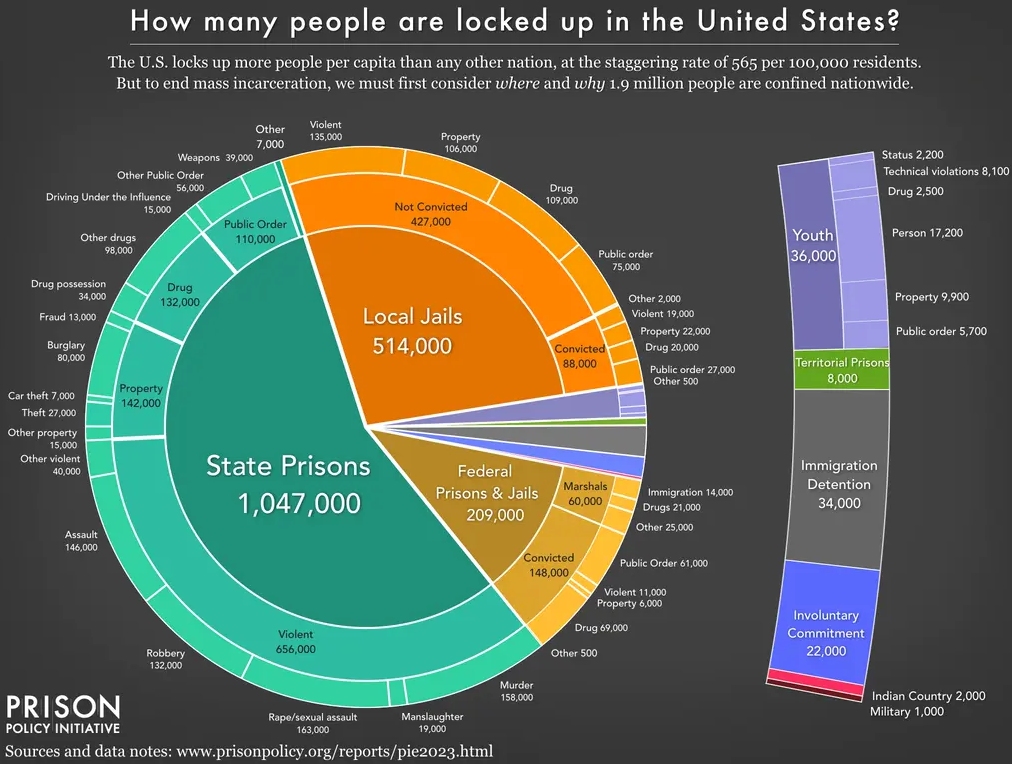

People from historically marginalized groups disproportionally make up the U.S. prison population of nearly two million people. Our nation’s imprisonment rates are higher than those anywhere else in the world, making U.S. prisons a big business with plenty of jobs to fill and plenty of imprisoned people needed to justify them.

“We don’t begin from the premise that there are criminals that need to be incarcerated and that the prison system can solve social problems,” explains Sbicca. “Instead, we see that certain people are marginalized and targeted by the prison system because other kinds of systems like education, housing, and employment aren’t available. The prison system attempts to deal with the resulting fallout of a failed political system, and it targets certain groups in doing so. So again, we stop to ask the question, who does the prison system, and by proxy agriculture, really benefit?”

The Prison Agriculture Lab is a collaborative space for inquiry and action and provides a platform for connecting with the public. Since launching, their work and analysis has been picked up around the country. Learn more by listening to Sbicca and Chennault’s recent interview on CSU’s podcast, The Audit.

Check out the Prison Agriculture Lab’s story map, Growing Chains: Prison Agriculture and Racial Capitalism in the United States. Stay tuned for an interactive map coming soon to the Prison Agriculture Lab’s website.