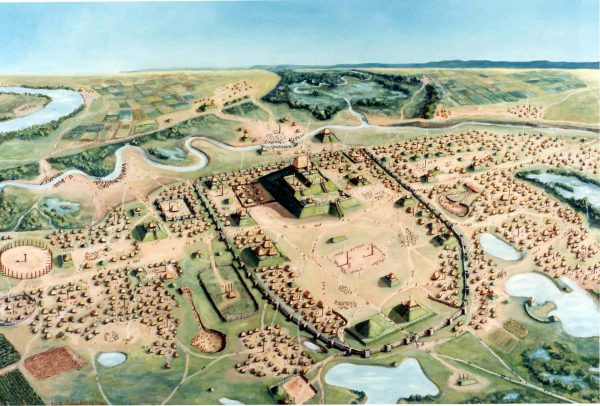

Rendering of Cahokia by William Iseminger. Courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.

What comes to mind when you think about the first city in North America? Roads and plazas, shops and sewer systems, neighborhoods and water distribution. Would you imagine Plymouth, New York, or Boston?

Due to carbon dating and other methods, we know that our first city was actually in middle America – right across the Mississippi River from what is now St. Louis, Missouri – with a span of six square miles and a population of up to 20,000 people.

We call it Cahokia.

Populated around 1050-1350 CE, Cahokia is the largest and most influential urban settlement of the Mississippian culture, who were known for building large, earthen platform mounds across the southeast, east, and Midwest U.S. about 500 years before European contact. Cahokia was multi-ethnic, metropolitan, and connected to numerous distant societies through trade and exchange. Now, Cahokia is a UNESCO World heritage site and managed by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

In the 1600s French settlers first recorded the mounds at present-day Cahokia. Later, in 1811, Henry Breckenridge, a frontier lawyer, described the mounds as a “stupendous monument of antiquity.” But it wasn’t until 1921 that Warren King Moorehead began examining the mounds, which were built of local materials – various soils and timbers. As a result, some mounds have worn away, or been plowed down by farmers, over the last hundreds of years.

Earthen mounds are evidence humans were creating a built environment. [At Cahokia] the base of Monks Mound covers more area than the Great Pyramid of Giza,” Henry says.

In recent years, archaeologists have taken a different, less invasive approach to understanding our historic past, by using digital tools to investigate what is below the surface rather than digging into it.

In May 2023, Assistant Professor Ed Henry, geoarchaeologist at CSU, with Drs. Casey Barrier (Bryn Mawr College), Rob Beck (University of Michigan), and Tim Horsley (Horsley Archaeological Prospection), will embark on a geophysical and digital exploration of Cahokia that will produce a comprehensive subsurface map of more than 5.5 sq km with a $312,000, five-year grant from the National Science Foundation.

Using shallow geophysical approaches to surveying the mounds and open spaces around them, Henry and his team will be able to “see” how Cahokia was spatially organized without disturbing the land. By using magnetometry instruments (funded by the Office of Vice President of Research, the College of Liberal Arts, the Department of Anthropology and Geography, and the Agricultural Experiment Station), that will be pushed and towed with a UTV, Henry and fellow researchers will scan the Cahokia landscape using a geoarchaeological approach to identify where there were homes, gathering spaces, refuse areas, and buried mound remnants underground.

By employing only geophysical methods on the mounds and surrounding settlements at Cahokia, Henry and colleagues are using a non-invasive and non-destructive way of looking at an entire archaeological landscape. “It is not invasive and is respectful of requests we have heard from several Tribal Nations with ancestral connections to the Indigenous city,” says Henry. “You can do a lot of work and cover a lot of area for less money and get previously inaccessible understandings into sites of this scale.”

Another important element of modern archaeological methods that emphasize “digital digging” are the incorporation of Tribal Nations and their interests and wishes relating to their ancestral places. “We recognize the important ancestral connection to the Indigenous past in this area. Several Tribal Nations assert ancestral connections to Cahokia and we are consulting and collaborating with tribal governments to ensure they have a voice in what we are doing, and become stewards and interpreters of the data we collect,” Henry says.

Perceptions of Archaeology

"Archaeology, in general, is beholden to the Indiana Jones stereotype – an adventurist running around the world. The amount and level of excavation being done now is far less than 20 years ago. Today, many archaeologists are not disturbing the ground or at least not in the same amounts. The tools and methods and technologies we use are advancing at a rapid rate and allow us to do different kinds of work to answer questions about the past.

People are using digital methods, consulting and collaborating with Indigenous communities, making their interest part of the research agenda and offering their voices to the archaeological past. Consultation with Tribal Nations is becoming more common and part of doing archaeology in an ethical manner these days." — Ed Henry

In the Center for Research in Archaeogeophysics and Geoarchaeology (CRAG), center director Dr. Edward Henry and undergraduate Anthropology student Margie Keith look at a soil micromorphology slide collected from an archaeological site in West Tennessee.

Henry, who grew up in Kentucky and got interested in archaeology during an undergraduate summer field school experience off the coast of Georgia, is director of the Center for Research in Archaeogeophysics and Geoarchaeology (CRAG) at CSU. The CRAG is a holistic geoarchaeology lab that uses digital tools to measure shallow subsurface properties in the earth. Henry and his students also use a variety of scientific methods to look at individual soil samples collected from excavations, which “gives us clues and insights to how people manipulated their environments in the past,” he says. “It tells us what kinds of environmental changes are more natural versus human-induced or completely intentional landform manipulations.”

Henry has been working at Cahokia since attending graduate school at Washington University in St. Louis where he worked with professors, local colleagues, and students on areas north of, and within, “Downtown Cahokia.” This includes a comparison of surface-based artifact collections from the 1990s with subsurface imagery to understand modes of craft production at the site fringes. Multi-instrument subsurface surveys in Cahokia’s Grand Plaza identified buried structures that revealed architectural changes at the site throughout its history.

For the NSF project, all data produced will be made fully open and available to other researchers with access and sharing controlled by the State of Illinois and tribal governments.

“What we hope to learn with this project is insight on how Cahokia is a city – how neighborhoods were arranged, what was the population density at its emergence. We will look at the size and shape of buried structures that can be mapped underneath the ground to see if some areas of the city are more densely occupied than others and try to extrapolate, from an urban planning perspective, why that might be the case,” Henry said. “My departmental colleague, Professor Steve Leisz, will do back-end calculations on the architectural remains we can identify to determine population density and clustering.”

Woodhenge at Cahokia

Woodhenge is a circle of upright timbers at the western limits of Downtown Cahokia. These were most likely used as celestial observatories to mark some of the solstice/equinox events. At one time, people invested a lot into the notion of Cahokia as a city of sun. But in the last 5-10 years, archaeologists have identified connections with built features and lunar cycles at Cahokia.

“This is the first project of its kind in the Americas. We have general expectations about the organization of neighborhoods and where they might be, but in terms of other urban infrastructure or evidence for pre-urban use of the landscape, we have no idea what we will find,” Henry says.

The insights from Cahokia could also help us understand how to plan our own cities today.

“The UN reports that most people on Earth (55 percent) live in urban areas and our work at Cahokia will provide a view on how Indigenous people created and experienced urban environments. Are there similarities to the design and occupation of other early cities in the world? Or are they doing something different that we might incorporate into the design and use of our cities today to make them more sustainable or equitable?” Henry says.

Do we know why they built mounds?

A lot of Indigenous creation stories across the eastern US talk about creation with a water-based creature pulling up mud and that’s where land came from. The construction of mounds could represent participation in the world’s renewal on earth.

Mounds were used for different reasons – they were platforms for feasting, social cohesion events (rectilinear mounds), contained revered members of the dead (conical mounds); they were also a reflection of the elites who conducted business on top of them.

The mounds also provide insight on collective action which creates social solidarity through large labor projects.

Though there were several mound-building societies throughout the Eastern Woodlands of the U.S., there is nothing comparable in scale or landscape modification to Cahokia. And the scale of this NSF funded project is something not yet accomplished in North America. The digital atlas that Ed Henry and his colleagues will produce is poised to become a new foundation for understanding early North American urbanism initiated by Indigenous people, further attesting to the global importance of this UNESCO World Heritage site.

“One of the enigmas of Cahokia is that we don’t know who exactly lived there. Lots of contemporary Tribal Nations claim an ancestral connection to the site, and it’s possible that, as a metropolitan center, many past societies that would later form tribal entities recorded by early Euro-Americans resided here,” says Henry.