Photo: Caleb González poses at the entrance of Harris’s home, which includes the official seal of the 49th Vice President of the United States.

When Caleb González (M.F.A., ’19) received an invitation to attend the Día de las Madres celebration at the home of Vice President Kamala Harris and Second Gentleman Douglas Emhoff last May, he did not believe it was real. Though the email appeared official, González’s mind filled with doubt. Me, really? How? Why?

Sure, he had written a letter to the Office of the V.P. earlier that spring to share the ideas his students had cultivated in his classroom at Ohio State University—but he never imagined he’d receive a reply, let alone an invitation to Harris’s house.

At the time, González was completing his fourth year of study in the Ph.D. Program in English at OSU. González specialized in rhetoric, composition, and literacy, and taught writing in the Young Scholars Program (YSP). Housed in the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, the program is described as “an exceptional opportunity for academically talented, first-generation students with high financial need to advance their goal of pursuing higher education.”

Listen to Caleb González read a portion of the letter he submitted to the Office of the Vice President.

In his letter to V.P. Harris (which was included in the Vice President’s monthly newsletter), González discussed how his YSP students were engaging with the current political moment through their writing. After framing his course around the theme of “Representations of K-12 Education,” González saw his students tackling topics like censorship and book banning, attacks on Critical Race Theory and threats to LGBTQIA+ rights in public education, and legislation on the Federal Free School Lunch for All program.

Their ideas were thoughtful, complex, and deeply tied to national issues that they identified as impactful to their lives. González thought someone should know.

“My hunch was that my students were writing about really powerful things about education from a wide range of perspectives and positionalities,” he said.

“They were learning what it means to situate themselves—their stories, backgrounds, identities, experiences, knowledges—and use their voices to shape the very discourses and situations that impact their lives, families, and communities.”

It struck a chord that González could not shake. As it turned out, he wasn’t the only one moved by his students. After a few frantic FaceTime calls with his sister and brother-in-law, González finally realized the authenticity of V.P Harris’s invitation. It was real, and he would accept. He was going to Washington, D.C.

From Student to Teacher

Like his students at OSU, González is a first-generation college student. Born and raised in Pueblo, Colorado, he attended the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, where he earned his B.A. in Spanish with a minor in creative writing in 2014.

Though González wasn’t sure what kind of career awaited him after graduation, he knew he wanted to keep writing. When he was admitted to CSU’S MFA in Creative Writing program in 2016, he was also offered a competitive graduate teaching assistantship in the University Composition Program. It was here, in Fort Collins, where his career in education and writing studies truly began.

Yet, González will be the first to tell you: His journey into teaching wasn’t without its speedbumps. In fact, his first year teaching composition at CSU was so rocky, he questioned whether he should pursue teaching at all. As a first-time instructor, he felt overwhelmed and stressed. He could tell his students weren’t engaged in the curriculum. They were bored, unmotivated.

“They just didn’t want to be there,” he recalled. “I was having a really hard time reaching them, and just struggling to connect.”

Despite these challenges, González never considered quitting. Instead, he asked for help from his mentor and then-director of the Composition program, Sue Doe (who is now the executive director of TILT).

“Caleb really took it upon himself to improve his pedagogy and improve his understanding of why students were feeling the way they were feeling,” Doe said.

While observing his class in the spring of 2017, she recognized that he needed to reset and restructure the classroom dynamic.

“Sue told me, give yourself permission to figure this out. Bring yourself, your experiences as a student, and your creative writing into this classroom,” González said.

Doe added, “All he needed was confidence because all of his instincts were right.”

Taking her advice to heart, González decided to switch things up and learn the curriculum alongside his students.

Noting that his section happened to have a robust Latine/x population, González observed an interest among many of his students to examine the harmful and destructive anti-immigrant rhetoric that was showing up on campus in connection to the tumultuous 2016 presidential election.

When one student asked if she could feature interviews with family members who are agricultural workers in Colorado for her essay that intended to challenge the myth that immigrants are ‘taking’ U.S. jobs, González saw an opportunity to reimagine what “counts” as a source in an analytical writing assignment.

“How could I, as a teacher who also has agricultural workers in my own family, further support my students’ knowledges, histories, languages, and learning assets through the teaching of writing?” he said.

González altered the assignment and allowed his students to use personal sources, rather than only peer-reviewed articles and a few popular sources, to enhance their essays. In bending this rule, a series of light bulbs began to flicker for him. He wondered: What does it mean to really support these students? How can we as educators actually meet them where they are?

“As somebody who often incorporates more than one language into my own creative writing, I questioned, what does it mean to support students who are coming into our writing programs, students who bring these really rich assets—linguistic assets, cultural assets, ways of knowing, ways of being—into our classrooms?” González said.

"As somebody who often incorporates more than one language into my own creative writing, I questioned, what does it mean to support students who are coming into our writing programs, students who bring these really rich assets—linguistic assets, cultural assets, ways of knowing, ways of being—into our classrooms?"

Combining Research and Teaching

Though he didn’t know it at the time, these questions would become foundational to his research at OSU. In centering the intersection of two fields, Writing Program Administration and Higher Education Studies, González’s current work identifies Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs) and emerging Hispanic-Serving Institutions (eHSIs) and how prepared they are to serve and support the students who have given them this sought-after designation.

“My research is about how First-Year Writing Programs at HSIs and eHSIs both shape and are shaped by this significant, yet very complex institutional identity,” González said, noting CSU became an eHSI in 2019.

“I want to know what it really means to support students through meaningful and impactful practices that are designed with equity, inclusion, and social change in mind,” he added.

“What Caleb is doing now is difference-making. His research will be important not just to the field of writing and composition, but more generally to institutional considerations around what it means to be a Hispanic-Serving Institution." – Sue Doe

Doe, who has remained a close mentor and friend, isn’t surprised by González’s impressive trajectory. She distinctly remembers when everything clicked into place for González at CSU and he became a leader among his peers, and within the English department.

“It was like this constellation of things,” Doe said. “The growing awareness of himself as a writer, of himself as a scholar, of himself as a teacher—all coalescing and erupting into what I can only describe as a scholarly intellectual confidence.”

“What Caleb is doing now is difference-making. His research will be important not just to the field of writing and composition, but more generally to institutional considerations around what it means to be a Hispanic-Serving Institution,” she said.

The Power of the Personal (Voice)

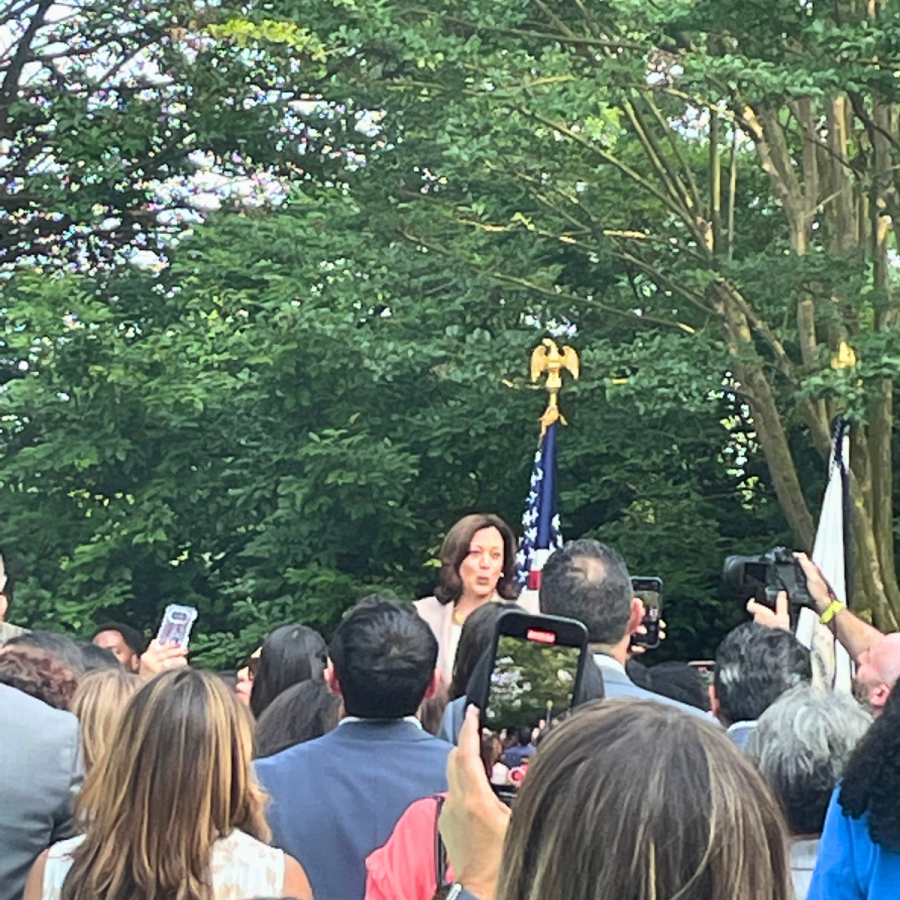

Back at V.P. Harris’s swimming pool, the Día de las Madres gala was made up of an excited crowd of educators and advocates, actors and journalists. González stood rightly among them.

While he admitted to being starstruck as he shook hands and conversed with actress Gina Torres and White House Correspondent for CBS News Ed O’ Keefe, González felt like he “was representing the broader Latine/x community in higher education, including the role that families have had in securing a place within this sphere.” During the event, Vice President Harris made a speech that has since stayed with González.

“Her speech was a reflection on what it means to create policies that center humans within immigration discourse and the ways in which the country has benefited from the presence and contribution of Latina mothers and their children,” he said.

Reflecting on the whole experience, González said he has ultimately learned that his story, and the stories of his students do matter and that writing and rhetoric are powerful.

“Through my letter to the Vice President, I learned what it means to appreciate and wield the power of our voices as we engage the issues that shape our education and our very lives. In other words, I came to appreciate the multifaceted nature of writing and what it can teach me about uplifting the work of others, especially those who are brave enough to advocate for change,” he said.

“My students taught me that when I feel like an ant in a seemingly endless terrain of voices, or someone who might want to say something about an issue but thinks, who would listen to me anyways? I’ll remember that my words and my voice do carry weight.”