Andre Archie stands out among philosophers. As both black and conservative, he is a rarity in a largely white and liberal field. Additionally, in the age of equity initiatives and the promotion of diversity pedagogies on college campuses, he stands against the tide by promoting a color-blind approach to race relations.

In his latest book The Virtue of Color-Blindness, Archie argues against using race as a tool to correct past discrimination and instead he argues that social policy should focus on the family, economic class, and on the moral character of individuals as potential sources for generating solutions to societal inequality. He doesn’t believe that opportunities for some should come at the expense of opportunities for others based on skin color, an arbitrary and non-moral trait. Drawing on his expertise in ancient Greek thought, the principles embodied in the Constitution, and the arguments of Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King, Jr., Archie favors the principles of fairness and equality over divisive “identity politics.”

Growing up in Park Hill

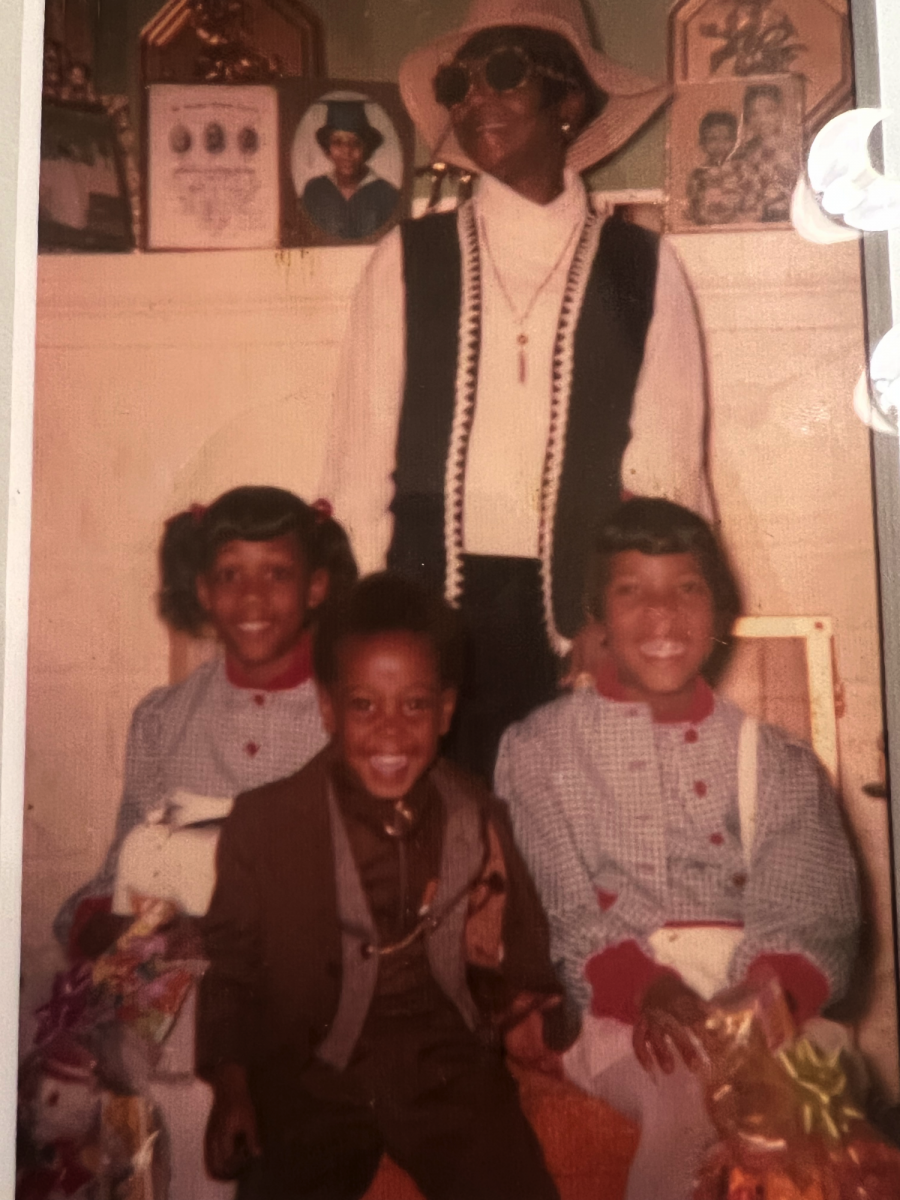

Archie credits his upbringing for shaping his views on race. Archie came of age in the 1980s in Denver and in the relatively integrated community of Park Hill—an intentional choice for his mother. He explains, “My mom emphasized that she wanted us to be in an integrated environment; environments that are equal and that treated us fairly. She raised us to be open towards other people.”

Archie’s mother did share her experiences of discrimination in her own life and her work in healthcare: “We heard stories of her being mistreated, possibly because of race, but it wasn't something that hampered her. She always emphasized that she didn't want us to see white people in a certain way.”

Archie appreciated the message of assessing individuals based on their individual actions and choices, rather than on arbitrary ascriptive qualities. He explains, “When it comes down to it, you can judge someone based upon their actions and their behavior. That's what was drilled into me and that's really the basis of the book. That has influenced me both in terms of how I raise my kids and how I approach my academic work. As the ancient Greeks teach us, character is the locus of moral agency.”

The Centrality of a Common Narrative

These principles of fairness and equality shape what Archie views as the “common narrative” of American society. “In a democracy what unites the many is a common narrative. And that common narrative is a sort of broad consensus. And it doesn't necessarily stifle others, but it makes sure that there's a common script, if you will.”

An impetus for writing The Virtue of Color-Blindness was the rise of divisiveness that Archie sees in contemporary society. “What I noticed with the emergence of identity politics back in the early 1990s and having really picked up steam since the death of George Floyd is that the particularities that define us, such as race, sexual orientation, and gender, have eclipsed the common script, that common narrative that we really need as a country, as Americans, in a diverse society such as ours. We need that. Otherwise, I think an emphasis on racial and ethnic particularities at the expense of a common narrative becomes potentially problematic and then ultimately dangerous.”

“My ultimate belief is that you need a core. It doesn't mean that the core can't be expanded, but you need a core. And I think those other sorts of identities start to compete with that core, and I find that sort of competition highly problematic in a society as diverse as ours. It's not that we can't learn about Chicano history or learn about African Americans, but those histories take place within a broader stream and it's that broader stream that I think we should all be committed to. Again, it’s not that the broader stream stifles the particularities of other identities. We can celebrate those other identities precisely because we have this broader American identity that's grounded in certain basic beliefs and commitments.”

For Archie, like many conservatives, this common core is grounded in the founding documents of our country and focuses on equality before the law and basic respect for individual agency. Archie admits that this doesn’t always pan out in practice, yet its necessity holds: “Now in practice, there's all sorts of factors at play that challenge the belief that all are equal before the law. And of course, I’m not ignorant of that but I think there's an aspirational sense that, as Americans, we strive toward, and we strive for.”

Andre Archie's address at the Miami National Conservatism Conference on September 12, 2022.

Accounting for Racial Disparities

In accounting for racial disparities for African Americans and others, Archie argues against the view that America is systemically racist. “I don't buy that. Of course, there's vestiges of the past. But what does it mean exactly that America is systemically racist?”

While acknowledging the controversial nature of the claim, Archie points to cultural differences to explain varying outcomes in education, healthcare, and in the criminal justice system.

When you have people within a culture associating education, the life of the mind, with 'acting' white [and not authentically Black], it seems likely that you’re going to have disparities in academic performance between groups. Those are cultural presuppositions that often hinder group performance; it hinders people when they are raised in environments that promote those ways of thinking."

He cites education as his primary example of possible explanations of disparities there: “I'm speaking from experience. I'm Black, I can speak about these issues more intimately. When you have people within a culture associating education, the life of the mind, with 'acting' white [and not authentically Black], it seems likely that you’re going to have disparities in academic performance between groups. Those are cultural presuppositions that often hinder group performance; it hinders people when they are raised in environments that promote those ways of thinking. When you think about it today, there are certain cultural presuppositions and certain cultural attitudes that I think, in particular for Black Americans, are detrimental, and we see that across the board. That's what people have a hard time talking about. We all pretend not to notice.”

While speaking generally and recognizing exceptions within groups, such as differences in the positive educational outcomes for Black Caribbean-Americans and those of Nigerian descent, Archie does believe culture accounts for a lot of discrepancies that we see among Black Americans. “Whereas others want to argue about systemic reasons, I think we need to be a little more complex about the matter and consider the role of cultural norms and expectations, especially in terms of education and upward mobility.”

Democracy and a Shared Identity

In The Virtue of Color-Blindness, Archie argues against the work of Derrick Bell, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Ibram Kendi and the divisiveness they fuel. Archie argues that we fail one another when “we put each other in boxes” according to racial categories. He claims that in a democracy this type of thinking is very problematic and should not be taken seriously. “Those ideas do not work in the long run because you have competing interests. If those competing interests are racially based, that's a recipe for disaster. The Founding Fathers of our country, for example, were especially sensitive to the issues that plagued ancient democracies, such as personal interests competing with the common good. In 1863, Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address faced this issue head-on."

Many may view this common narrative as just one story, the story of privileged white Americans. However, Archie doesn’t believe that to be the case, citing his own family’s experience. “I think that we've come far as a country. I think that argument could have been made justifiably 50 or 60 years ago. Things aren’t perfect, of course, but I think our democracy is much more comprehensive now. In terms of my own family, when I talked to my mom and my dad about their experiences coming of age, and I think about civil rights legislation, we can see that all of that has extended and expanded what it is to be an American.”

For Archie, the essence of what it means to be an American is grounded in respect for each other’s autonomy and agency. The focus is on the individual, rather than the group. He explains, “Until the individual acts in a way that you disapprove of, or you approve of, basically until they show you who they are in terms of their character, you should take them at face value. Their race shouldn’t enter into it.”

“I think that in a self-governing system such as ours, we need a common script. We need to be reading off the same page. Not verbatim, but in general. And it's that ‘in general’ aspect that I think defines us as a democratic republic and as self-governing citizens as opposed to having competing scripts that make any sort of compromise impossible. I think our representative democracy works well when we work within the framework of a shared identity.”