oil & gas • criminal justice system • local school district

Evelyn’s home of 30 years now has a 20-foot sound wall just 8 feet from her bedroom window. The wall is oil and gas operators’ attempt to minimize the noise of 200+ semi-trucks that began driving 15 feet from Evelyn’s home each day when multiple wellpads were sited in the open space behind her house. She had no power to say “no” and no economic ability to move from her home. In addition to Evelyn’s hearing and mobility impairments, she now feels chronic stress and depression.

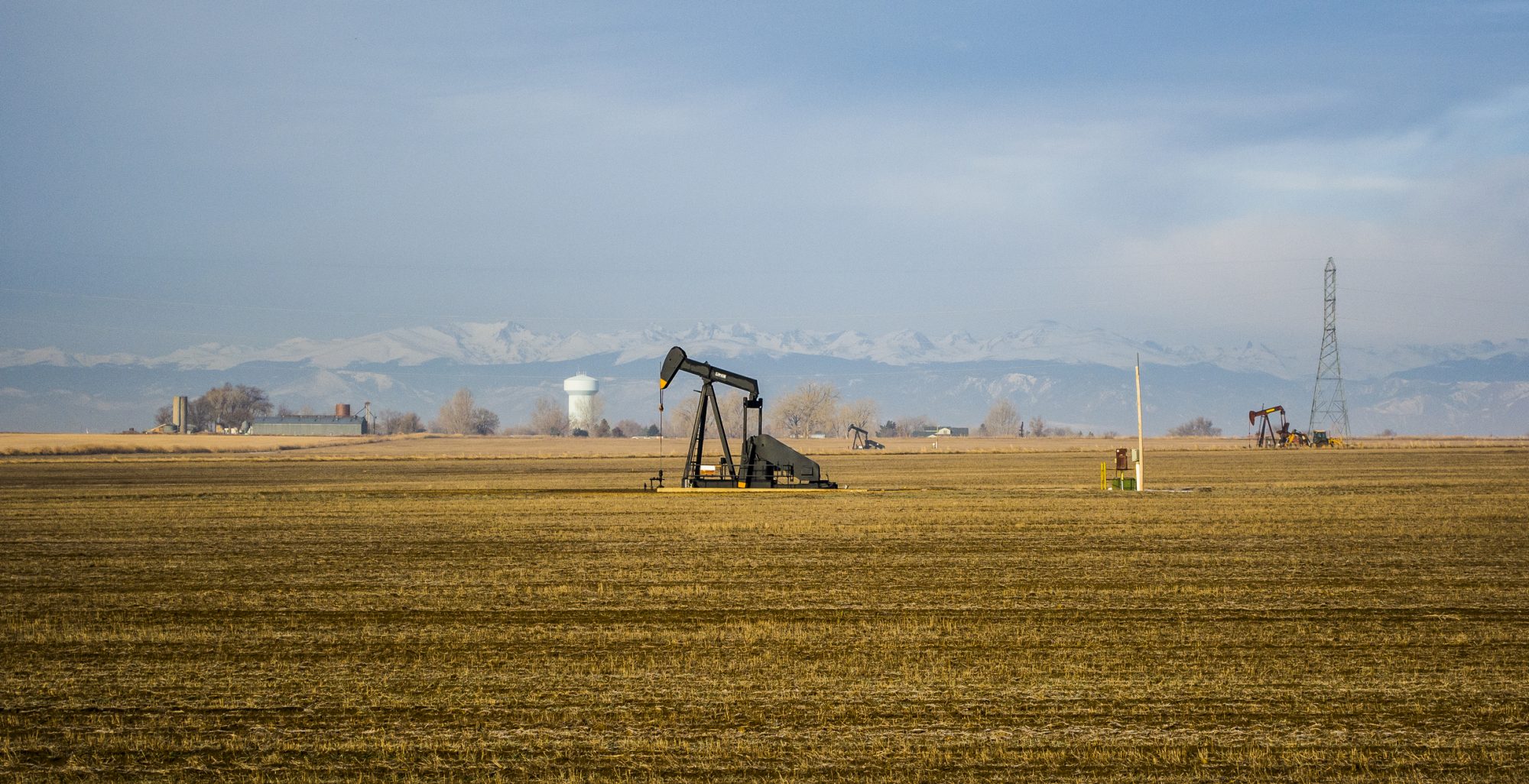

Multiple well pads were also placed near a school in Weld County, just over 1,000 feet from its athletic fields. Despite protest and widespread concerns over the potential health risks to children, the well pads were constructed. Residents of the area had little opportunity to participate in these decisions. The school serves primarily poor and minority students, with about 89% Latine enrollment and 92% of students coming from low-income households. Some of these households included undocumented people as well, adding to their vulnerability and inability to organize or speak out about their concerns.

Stephanie Malin, associate professor of sociology and founding co-Director of CSU’s Center for Environmental Justice, works with Colorado residents such as these whose homes and schools are in close proximity to hydraulic fracturing sites. Many of these residents feel their voices and health concerns are ignored by local, state, and federal policymakers, as well as by the oversight agency (that doubles as the permit issuer) for the oil and gas drilling industry in Colorado.

With funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Malin has conducted surveys, over 100 interviews, observations, and biomarker collection for a research project that found important links between living in close proximity to drilling and impacts to people’s health and wellbeing.

For example, residents’ continued feelings of uncertainty and powerlessness not only result in chronic stress, depression, and declines in physical and mental health, but are driven by the state-level systems – elected officials, oversight agencies, and institutional processes – that are supposed to ensure public health. The inadequate access to transparent information about the effects of drilling and the limited opportunities for public participation in decision-making create a “depressed democracy.”

Malin points to procedural justice as the remedy. “Everyone affected by a decision, especially those most impacted, should have useful information translated for non-specialists and in all relevant languages so they can then help shape policies,” she says. “This is especially true for historically and currently marginalized populations.” Opportunities to meaningfully participate in making decisions about drilling, such as where well pads might be located, are central criteria for upholding procedural justice in these communities. Hear more about Malin’s work in The Audit podcast from CSU.

Participatory Action Research Is One Way to Practice Procedural Justice

Sociology often examines who wins, who loses, and if decisions are made fairly. Driven by social justice concerns, procedural justice is an approach to decision-making that is inclusive and deliberate. As CSU sociologists explain, this is vital to upholding democracy because the effort values multiple voices, fair processes, transparency, impartiality, and trustworthiness.

Participatory action research (PAR) is one way procedural justice can be enhanced. Instead of conducting research on a population, researchers like Tara Opsal, associate professor of sociology, conduct research alongside the people who will be most impacted by a project’s results. Currently she is working with Larimer County’s Community Justice Alternatives (CJA) on programming and policies for the county’s new residential facility for women.

“Having clients and staff involved at every stage, from research design to implementation decisions, is the best way to determine the most responsive programming. Together we continually refine what works and what doesn’t,” she explains.

For instance, Opsal and her research team involved staff as well as current and former clients in figuring out what questions needed to be asked in interviews and focus groups so that the project (determining programming and policies) would be most effective given the participants’ and staff members’ perspectives and experiences. The same engagement occurred when Opsal asked staff and clients to review the major findings and identify what she got right, got wrong, and what needed to be fine-tuned.

Participatory action research requires that an organization value the perspectives of their participants as humans.”

Opsal says organizational commitment to a participatory process is key because many resources are needed to overcome structural, cultural, and legal obstacles. “Participatory action research requires that an organization value the perspectives of their participants as humans,” she notes. As such, four years ago the county began receiving Justice Assistance Grants from the State of Colorado’s Division of Criminal Justice to have Opsal, alumna Alex Walker, Ph.D. (‘20), and Sociology students evaluate the county’s gender-responsive programming in anticipation of the new facility.

Through participatory action research funded by the United State Bureau of Justice Statistics, Opsal's team formulated a 70-page report based on their research. To determine priorities, Opsal is working with CJA to create an advisory council comprised of staff, current or former program participants, community members, and community-based service providers. Guided by gender-responsive principles, this participatory group will review current policies tailored to the needs of women whose trauma and sentencing experiences differ from those of the men they were formerly housed with (in separate wings), and the group will play a central role in guiding the future initiatives of the organization.

“CJA focuses on holding those who are under our supervision accountable for their actions while creating a positive approach and path for these justice-involved women, providing them with skills and resources as they transition back into the community,” Emily Humphrey, CJA director, recently told The Collegian.

Procedural Justice to Deescalate Police Interactions

As police officer interactions are common entry points into the criminal justice system for women and historically marginalized populations, Jeff Nowacki, associate professor of sociology, investigates how procedural justice is utilized in preventing unfair treatment that could lead to incarceration. He, Megan Parks (M.A. ‘19), and their research team recently studied body-camera footage from more than 700 police encounters and specifically looked at how on-the-street decisions are made.

Nowacki and Parks’ team found that outcomes during police interactions can be improved when officers utilize seven procedurally just measures. These include:

- the officer clearly stating the reason for the interaction

- offering an explanation of why it’s problematic,

- asking for input from the community member,

- acknowledging the input,

- explaining next steps,

- expressing concern for the community member’s wellbeing,

- and then offering empathy.

When these steps are incorporated into police trainings and then put into practice, de-escalation is more likely. As Nowacki explains, “When community members feel that their voice is being heard, they’re being treated fairly, and their input is valued, they are more likely to be supportive of police processes and trust police officers.”

Community Engagement Key to in Procedural Justice

Trust is also central to the work of Jeni Cross, professor of sociology and co-founder of CSU’s Institute for Research in the Social Sciences, as she studies behavior change and social networks. She often uses participatory action research both in practice and in her courses in social change. The challenge she has undertaken most recently is helping local parents and students make their voices heard after an abrupt decision by Poudre School District to consolidate several schools without community input. The decision to merge schools directly affects more than 1,000 students and raised frustration across the district.

“The emotional and rapid response from the community reveals the lack of procedural justice in this case,” explains Cross. “The school district proposed radical changes, without community engagement, a distinct departure from their past behavior.”

Students and parents protest the Poudre School District's decision to consolidate several schools without community input. Photos courtesy of Jeni Cross.

Within days of the announcement, students and parents organized a response, created t-shirts, signs, and a website that helped unify all schools affected. They engaged the media, organized a walkout, invited board members to a weekend gathering, protested outside a school board meeting, and organized speakers at the meeting. When the parent group from Polaris Expeditionary Learning School realized all of the speaking slots had been taken by parents from only two schools and couldn’t be transferred, the organizing group reached out to unrepresented schools and incorporated their perspectives.

Cross put her social science expertise into action and helped the group articulate three talking points: “give us time” by delaying approval of the plan and slowing down the process for such radical change; “preserve our culture” that is successfully serving the district’s most vulnerable students; and “engage the community” sincerely in creating solutions to challenges faced by the district. The district has since postponed the board’s vote and slowed down the consolidation process.

Procedural justice, which engages all affected parties, not only reduces conflict and uncertainty, it also produces more creative solutions and outcomes that are better for communities. As Opsal explains, “Procedural justice is such a unifying concept. Change actually happens when organizational transformation occurs and there’s a seat at the table for the people most affected.” Malin agrees and points to “affected parties authentically participating in decision-making AND having access to useful, translated information.”