Giving voice to Kenyan forest managers

More than 80% of people in rural communities in Kenya rely on forest resources and biomass for incomes, energy sources, and livelihoods. Forest products often supplement agricultural foods, and wildlife and livestock also rely on forests for habitat and space. But decades of deforestation and environmental change have diminished Kenyan forests. Climate change is also bringing additional challenges and forcing new management approaches for forest landowners and managers.

Facing ecological and technical uncertainty, a NASA-funded team of Colorado State University researchers, including University Distinguished Professor of Anthropology and CSU Africa Center Director Kathleen Galvin, and conservation partners in Africa have launched a new interactive, online tool to enable Kenyan and African land managers and foresters to address and halt negative forest trends.

The collaboration and user-friendly app – called the the Kenya Afforestation Decision Support Tool (DST) – will support broader planning objectives developed in Kenya, where the government has initiated planting 15 billion trees by 2032 to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and to restore deforested and degraded landscapes. The app displays climate-change impacts and effects to forest cover and growth across different scenarios and will allow managers and non-scientists to better prepare for and adapt to actual climate changes.

“The decision support tool will be instrumental in helping all relevant stakeholders in achieving Kenya’s government plans and goals,” said Anderson Kehbila, Research Fellow and Programme Leader for Natural Resources and Ecosystems with the Stockholm Environment Institute, based in Nairobi, Kenya.

“Knowing how trees might fare under different climate and disturbance scenarios with use of this decision support tool will help in planning for reforestation,” Galvin added.

Preparing for and adapting to climate change

Loss of forest acreage has been unfolding in Kenya for decades due to human uses and development as well as natural factors including drought and climate change. A 2013 ecological survey revealed the country had less than seven percent of national forest cover, well below national benchmarks and United Nations recommendations. Kenya’s government responded to that dismal tally with its plans to plant 15 billion trees by 2032.

Kenya’s planting initiative has since begun to reverse that trend, and the effort aims to reach 30% forest cover in the next decade. But reforestation and climate mitigation strategies will only succeed if managers have accurate and current data to be able to recognize near- and long-term climate and land-use trends.

Patrick Keys, assistant professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science — previously a research scientist at the School of Global Environmental Sustainability — saw the changes and initiatives surrounding forest management in Kenya as an opportunity. In 2018, he teamed up with Galvin and Randall Boone, a professor in the Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, to put forth a proposal through the Colorado Water Center to study and support sustainable forest management in Kenya.

“I wanted to put together a team that merged our expertise, thinking about how changes in forests might affect both the atmospheric water cycle as well as communities that depend on the land for their well-being,” Keys said. “It was critical for this project to have personnel from not just different departments, but also from various backgrounds, levels of experience, and expertise. The project would simply not have been possible without any one part of the team.”

The group won the Water Center funding and then expanded their vision and earned a three-year NASA grant in 2019 and other funding to continue their work, including working closely with partners in Kenya.

Collaborating to conserve forests

The CSU team — which includes faculty from the Department of Atmospheric Science, the Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, CSU Geospatial Centroid, and the School of Global Environmental Sustainability — reached out to colleagues from the Kenya Forestry Research Institute and Kehbila and others from the Stockholm Environment Institute to forge a plan and eventually develop the Kenya Afforestation Decision Support Tool.

“We asked our partners in Kenya, specifically KEFRI and SEI Africa, what would be helpful for decision-making with regard to these tree-planting ambitions,” Keys said. “The answer was better information about what climate change might do to affect the success or failure of trees and forests in different parts of the country. So, the web application that we’ve co-designed provides an intuitive look at how climate change might affect the success of trees across Kenya.”

Decision-support tools help in planning and management by harnessing spatial and field data and computer modeling to offer projections of different environmental and management outcomes.

“The current challenge is we have complex modeling tools that are beyond the expertise of technicians,” Kehbila said. "The DST provides a user-friendly experience to non-scientists and others for visualizing information that support decision-making and planning of reforestation projects.”

Managing forests? There’s an app for that

Climate modeling is — no surprise — technical and complex. Decision support tools and systems are valuable because they share data to stakeholders via a user-friendly interface, said Caitlin Mothes, research and program coordinator for the CSU Geospatial Centroid, who led the development of the DST app.

The web-based tool “transforms raw numbers into decision-relevant summaries, visualizations and reports,” Mothes said. That provides findings in a way that makes it easiest to incorporate data into decision-making processes.

No less important than the user experience is ensuring that DSTs run on the best data and most appropriate modeling. Postdoctoral researcher Rehka Warrier led the climate-change analysis and ecological modeling for the program, acquiring forest-cover and climate datasets for Kenya and then determining an existing ecosystem model program that could effectively simulate Kenya’s climate futures. Since Kenya is a country dominated by savannas with relatively small patches of forests, modeling how forest cover might change or encroach on grasslands under different climate scenarios is that much more challenging, Warrier said.

Fine tuning

While the COVID-19 pandemic hindered plans to engage and collaborate with Kenyan land managers and officials on the ground, that time proved useful for Warrier and Mothes to, respectively, fine-tune the modeling and develop the decision support tool into an accessible and easy-to-use web application. When the CSU researchers finally traveled as a group to Kenya in June 2023 to meet with Kehbila and Vincent Oeba of KEFRI, they were also able to roll out the app at a workshop and training for a group of land managers and stakeholders.

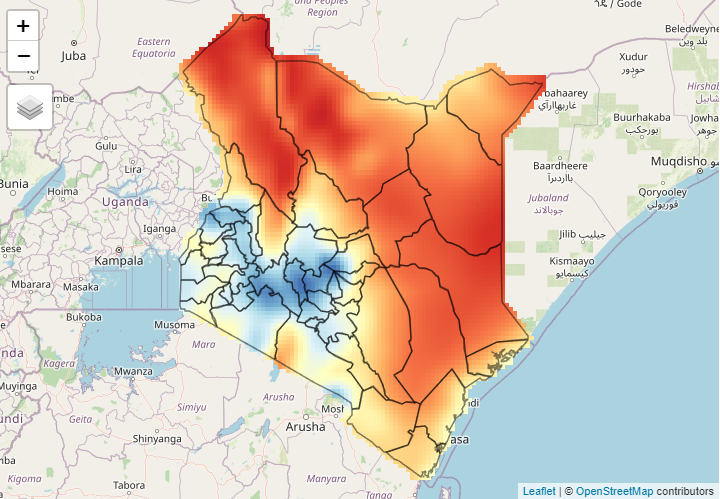

The beta version of the Kenya Afforestation DST allows users to model and “visually explore” different climate futures, ranging from optimistic to extreme pessimistic scenarios through the year 2100. The tool projects data across different “ecological scenarios” that represent various levels of forest cover, temperature ranges, and fire risks. The data is presented to users via interactive maps and downloadable summary reports.

“The DST is a tool that allows Kenyan forestry practitioners and policy makers to visualize how trees are likely to fare under dramatically different future temperature and precipitation conditions,” Warrier said. “We did not envisage DST as a tool that identifies areas where trees should or should not be planted. Instead, we intend it as a tool that allows forest managers in Kenya to appreciate the dynamic nature of vegetation across Kenya’s landscapes and how climate change modulates this dynamism.”

“Users can view and interact with the spatial distribution of predicted climate-related changes across the entire country, which I felt was a unique aspect to many of our participants,” Mothes added. “Also, the fact that it is an open-source, web-based tool means Kenya foresters and other stakeholders can easily share this tool and its information among colleagues and other interested parties.”

"The fact that it is an open-source, web-based tool means Kenya foresters and other stakeholders can easily share this tool and its information among colleagues and other interested parties."

Workshop success and what comes next

A post-workshop survey showed that 100% of the workshop participants said they were likely to use the application in their professional activities.

“Workshop participants, mostly agency scientists and academics, were really interested, insightful, and engaged in the potential of the DST,” Galvin said. “The workshop was high energy, and the atmosphere was very positive. It was a pleasure working with the group.”

Mothes echoed that sentiment. “I think quite often these kinds of tools are built but don’t quite reach their intended users to really make a difference in some decision-making process,” she said. “Whereas we got to carry out a hands-on, in-person workshop for people that showed so much interest and excitement to use it. This was an extremely rewarding trip with really positive outcomes.”

“The DST is providing guidance for Kenya forest managers,” Kehbila added, “to integrate climate information into the design, implementation, and evaluation of reforestation projects,” fulfilling important niches and knowledge gaps to carry out those projects.

The CSU research group fulfilled the NASA grant work with the support-tool demonstration this summer. Keys said there is interest from KEFRI and other partners to expand the app’s modeling capabilities, datasets, and focus area, leading the team to now pursue more NASA funding.

“This would be very exciting, not least because it would permit an actual demonstration of the concept of ‘science-to-policy,’” Keys said. “The CSU team has built exceptional partnerships with our in-country partners, and we now have other expanded collaborations that we’re discussing. It’s hard to say what comes next, but we’ve got lots of ideas.”