When you think about diversity and food, what comes to mind?

Perhaps selecting from a colorful array at the farmers’ market, or trying new and flavorful dishes while traveling. Maybe pinning new recipes, or being sure to eat from each food group every day.

But what about the diversity of our food sources?

More and more of us are concerned with where our food comes from. We frequent farmers’ markets and farm-to-table dinner events, join CSAs (community supported agriculture), and maybe even pick some of our own vegetables.

Our community leaders are concerned, too, and many have begun incorporating food into urban plans and policies to address issues of public health, local food, or economic development. These plans include funding for grocers to offer affordable and nutritious foods in underserved communities where such goods are scarce, offering tax credits to farmers who donate excess produce to food banks and pantries, revising zoning codes to allow farmers’ markets and produce stands. But how do such urban plans affect farmers and rural societies?

Two Colorado State University professors are leading the charge to better understand the linkage between rural and urban communities, their respective well-being, and how these diverse worlds interact with the food that comes across your dinner table.

Michael Carolan is a professor of sociology and the associate dean for research & graduate affairs for the College of Liberal Arts. He grew up among farmers in rural Iowa and has hand-harvested bushels of asparagus and de-tasseled acres of field corn. He is an international thought leader on food systems and was recently awarded the University of Aukland’s 2018 Presidential Fellowship (New Zealand).

Becca Jablonski is an assistant professor of agricultural and resource economics in the College of Agricultural Sciences as well as a food systems Extension specialist. Her early days as a farmworker and winemaker apprentice were followed by numerous appointments with the federal government and four years as an agricultural economic development specialist for Cornell Cooperative Extension of Madison County, New York.

Together, Carolan and Jablonski lead CSU’s interdisciplinary food systems research team “Rural Wealth Creation: Exploring Interactions Between Food Systems and Community Development.” Their goal is to better understand how urban food policies can sustain urban communities, while also offering opportunities for rural providers.

Impacts on Socially Diverse Communities

Food systems include not only how our food gets from field to fork – planting, harvesting, processing, packaging, distributing, marketing and consuming – but also nutrition, public health, people, communities, resource management, food disposal, and more. As cities form committees and councils to address challenges in the food supply chain or improvements in nutrition and public health, the rural providers who grow and raise most of our food are often not included in the conversation. When a public health official or nutritionist says to eat more fresh fruits and vegetables, we must consider where those fruits and vegetables are coming from: who is growing them, who is picking them, who is processing and packaging them, and how these consumer desires impact the rural communities from which we get most of our food.

“What are the impacts [of these urban policies] on the rural producers and communities – impacts in a really broad sense, not just economic and ecologic? How can we help ensure the voices of America’s rural are being heard?” asks Carolan as he describes the food systems team’s research question.

The team is using the City and County of Denver’s innovative new Denver Food Vision program, its "winnable goals" and forthcoming action plan as a case study to develop a framework, models, and tools that will aid policymakers in understanding how urban food policy affects people in different regions. The team will study the impacts of urban decision-making on the social, political, cultural, physical, financial, natural, and human issues in rural communities —and will focus especially on the inevitable trade-offs that will occur as a result of those decisions.

“Our team can actually test some of what the vision laid out and help the city, adjacent counties, and neighborhood to better evaluate potential trade-offs between different interventions, programs, and policies,” says Jablonski. “Our job is not to tell communities what to do, our job is to give them information.” This includes a scalable and replicable model of Denver’s food system as well as best practices to support food system policies that better build bridges between urban and rural places and people.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

The collaboration between the two colleges is important, with Carolan providing expertise on social impacts regarding which providers, producers, and consumers win and which lose, and Jablonski providing expertise in agricultural economic development. “We aren’t going to solve the challenges of the world by staying in our disciplinary silos,” says Jablonski.

CSU agrees. As part of a recent $1 million investment in interdisciplinary teams who are addressing some of the world’s most pressing global problems, the Office of the Vice President of Research (OVPR) awarded the Food Systems team $200,000 and infrastructural support to continue their uncommon collaboration — uncommon because the core team consists of 19 faculty from 14 disciplines and five colleges working in cooperation with numerous community and industry partners. This award follows seed funding the team received in 2016 through the OVPR’s PRE Catalyst for Innovative Partnerships (CIP) program supporting early-stage research projects that explore high-impact ideas and translate discoveries into practice.

“CSU's CIP funding is an investment in us and in forming a transdisciplinary collaboration to solve real-world problems. It’s not a typical grant because it allows for flexibility as we go,” says Jablonski. “I see this as a 10-year+ project. It’s a good example of the university’s engaged scholarship.”

Beyond the Dinner Table

In Carolan’s book No One Eats Alone, he investigates foodscapes – a way of also emphasizing the social, cultural, and political elements that shape what and how we eat – and says that food is more complex than a commodity chain. Food involves questions of power, culture, relationships, feelings, citizenship, and more. “Food is complicated because it can both connect and separate us,” he says.

Julian, a community activist living in Denver, told Carolan, “The more I’m involved in these regional food initiatives, the more I’m convinced that food and agricultural policy are inseparable from community development and public health initiatives. I’m interested in growing healthy communities. I really don’t care about how much vitamin C or dietary fiber a food has. If it’s destroying communities, it’s unhealthy. End of story.”

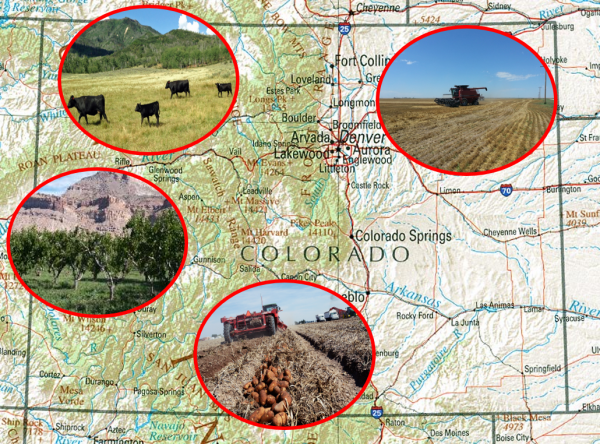

Research on food and food systems over the past several decades has focused on the production side, from breeding to pest management. The CSU Food Systems team’s research will focus more on people. And that means considering the socioeconomic, geographic, ecological, occupational and cultural diversity of producers and consumers. The Food Systems team intends to focus its rural efforts in four commodities and Colorado communities: fruits and vegetables from the Western slope, cattle in northwest Colorado, wheat and small grains out on the eastern plains, and, in cooperation with the Colorado Potato Administrative Committee (CPAC), potatoes from the San Luis Valley. The team is working to bridge conversations between the rural communities and urban consumers, recognizing that there is changing consumer demand for and interest in a range of food and agricultural products.

Tom Vilsack, CEO and president of the US Dairy Export Council, former US Secretary of Agriculture and Iowa governor, met with the Food Systems team earlier this year to discuss the team’s vision and scope. A prominent voice for rural America, Sec. Vilsack agrees that universities cannot ignore rural communities and they must talk about food and agriculture together. His meeting with the team aimed to help ensure that CSU, thanks to projects like Rural Wealth Creation, continues to serve the needs of its constituents, including those with a rural route in their address. “Agriculture holds the key to finding solutions to the world’s largest problems,” Vilsack says.

The Food Systems team is just beginning their exploration of the relationship between urban food policy and the rural community’s ability to fulfill them. Their hope is to shed light on how to improve conditions for people in both communities.

As a land-grant university, CSU has a stake in ensuring all people can participate in our nation’s economic and social progress. Through research and engagement, CSU’s Food Systems team is improving the quality of life for people in Colorado and around the world one dinner plate at a time.