The scene doesn’t seem extraordinary on the surface – a young girl speaking to her grandfather, her mother off to the side. But for Robin and her family, the moment is a momentous occasion. For the first time, the grandchild and her grandfather can communicate with each other in his native tongue, French.

Robin’s mother, like many other Louisianans in her generation, is unable to speak French largely due to the Americanization of Cajun, Creole, and other native cultures in the mid-twentieth century. But efforts by immersion schools – schools where 50 to 75 percent of content is taught in a language other than English – are hoping to revive and preserve the French language in those communities.

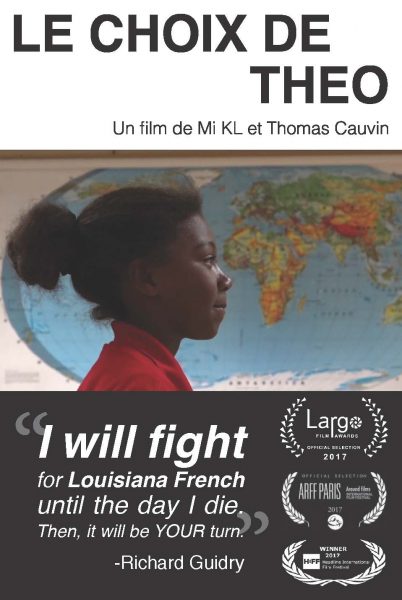

Assistant professor of history Dr. Thomas Cauvin's new documentary film, Theo's Choice/Le Choix de Theo, takes viewers into French immersion classrooms of southwest Louisiana. The film explores the complex Cajun identity through the idea of choice - the choice to speak, learn, and sometimes even teach, the French language in modern Louisiana.

Cauvin explained, "Speaking French in Louisiana is very different from Quebec, for example. If you're born in Quebec, French is a right to fight for. In contrast, in Louisiana, people can speak French, but few fight for it. Fighting for rights is not part of the Cajun culture. Fighting for your country, yes, but not rights. That has a negative connotation. French is more family-based, not rights-based. So choice - personal choice - is everywhere in this film."

The film's namesake figure, Theo Brode, made the rare choice to both learn and then teach French in his native region. Additional vignettes in the film, like that of Robin and her grandfather, are shared to echo this theme of choice and to support an underlying activist stance to promote French.

Choosing a Language, Choosing an Identity

Dr. Cauvin became interested in the topic while teaching at the University of Louisiana in Lafayette. His wife taught for an immersion program, where they met many French teachers and became part of the network French speakers in the area. There was a real interest from the community in Southwest Louisiana to learn more about the struggle to preserve French through education, whether from nostalgia about the past or concern for the future. Those questions posed by the public about preserving French through education, and the demand for answers, is what makes Cauvin’s documentary a public history project: history that engages the public.

“There have been tons of documentaries about [French heritage] but many less about school and how school contributes to preserving French. We wanted to show how school participates in that process and how local networks of French speakers were successful because they were connected to international networks of French speakers,” Cauvin said.

According to Cauvin, there was a lot of resistance to French before the 1960s. It was the language of farmers, a sign of backwardness. One young woman, in a historical video clip in the film, explained that she did not want to speak French because French wasn't chic. Attitudes changed in the 1960s, however. Music like zydeco received national attention. With political support, the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) program started in 1968, and brought international French-speaking teachers to the region to teach immersion classes in Louisiana schools. By the 1980s and 90s, French became cool again and the immersion program continues into the present, influencing the life and work choices of young Louisianans.

While Cauvin’s film looks at the community and student experience of French, the film also looks at identity development through the contact between the international and the local. Only about 5% of the French teachers in immersion classrooms are American. Immersion teachers come to Louisiana from France, Belgium, Senegal, the Ivory Coast, the Caribbean, and Quebec – almost the whole Francophone world.

While the contact with French speakers from around the world is often beneficial, the film does include some of the difficulties these teachers face. For most, the teaching experience in Louisiana is a shock. In France, for example, the average time that a middle-school teacher spends in front of the class per week is 18 hours. In Louisiana it is 40 hours. Prep time is very limited, resources are limited, and the administrative duties are very different.

"The teachers talk about how they can survive in the U.S. system," Cauvin said. Oral histories revealed that the international teachers felt separated from the local community, even from other non-US French teachers. They did not necessarily feel part of larger Francophone world when they arrived. But after the culture shock passed, and if they stayed long enough, that sense of connection with other French teachers could grow. While the teachers taught local students about the wider world, the teachers themselves also learned about the local French culture and worked to become part of the local Francophone network.

Cauvin acknowledges that the film is predominantly about the Cajun community, which is mostly white. Other Louisiana French identities, such as Creole communities and the Houma Nation, are only glimpsed. "These groups don't really mix. You don't have one strong French movement, like you do in Quebec."

"We shot the film in southwest Louisiana, which is more Cajun. With our small budget, we could not cover a lot of territory. And Cajun groups were better at getting political support from the state legislature, so their history is better documented in some ways. It was also much more difficult for us to connect with Creole communities, and even more with the Houma Nation. Trust was very difficult to develop in the time that we had. We had no way in to their community, and they had no reason to trust us," Cauvin explained.

Most documentaries like this one may have a budget of $40,000 and a 10-15 person crew. "We had only two people for everything and $2500."

Public History Means Being Part of the Public Debate

For Cauvin, who is the president of the International Federation for Public History, and author of Public History: A Textbook of Practice, community trust and involvement is crucial to any historical project: the community that shares their knowledge and the audiences who seek out the finished product both shape the project.

How people use the past and talk about the past is an important part of present-day politics. Historians analyze the past, but Cauvin argues that they can also shape policy. "I don't want to leave the floor to others; I want to be part of the debate. I always try to link my research - a book, article, or this documentary - with what is going on now. And I incorporate that in my teaching. I connect my classes to debates through the topics I ask students to research." So far at CSU Cauvin's classes have explored monuments and immigration. "We don't come up with an answer for contentious questions, like what to do with Civil War monuments, for example. There is not one answer. There is always context, and that is what historians bring to the debate."

"There is not one answer. There is always context, and that is what historians bring to the debate."

―Thomas Cauvin

Putting History on Screen

Theo's Choice/Le Choix de Theo is Cauvin's first documentary. Co-creator Mikael Espinasse did most of the editing. Cauvin did a lot of screen writing, oral history, research, interviewing on camera, marketing, and working with festivals.

That hard work paid off with a surprising number of requests from universities, libraries, communities, and schools all over the U.S. who want to show the film because it speaks to a grassroots trend toward bilingual education in the U.S. that is growing. The film premiered at the Cinema on the Bayou Film Festival in January and surpassed 180 other films to take home the Audience Prize. Denver’s Alliance Francaise showed the film on April 12.

Visit Theo’s Choice Facebook page for a list of all future showings. If you’re interested in organizing a public showing, you can contact Cauvin through that page.