Katie McShane is an ethicist; Idris Hamid is a metaphysician. She studies a love of place; he investigates dimensions of space. She tackles environmental policy discourse; he’s knee-deep in Islamic cosmology. Although these thinkers come from different worlds personally and philosophically, they do share a common perspective on what’s lacking in modern conceptions of place and space—a sense of value.

The absence of value

McShane, an environmental ethicist, says that our sense of ‘place’ can be very vague: “For some, it’s their favorite sunny spot in the living room, their hometown, or the Rocky Mountains.” Regardless of the specificity, it is this kind of personal connection that seems to be the defining feature of what we consider ‘place.’ However, it is precisely this personal engagement that McShane sees lacking in most environmental policy discussions. Instead, McShane explains, “A cost-benefit analysis model is dominant—how is the environment useful to us? How much can we extract? In this way of thinking, the emotional aspect of the environment, of nature, of place is absent.”

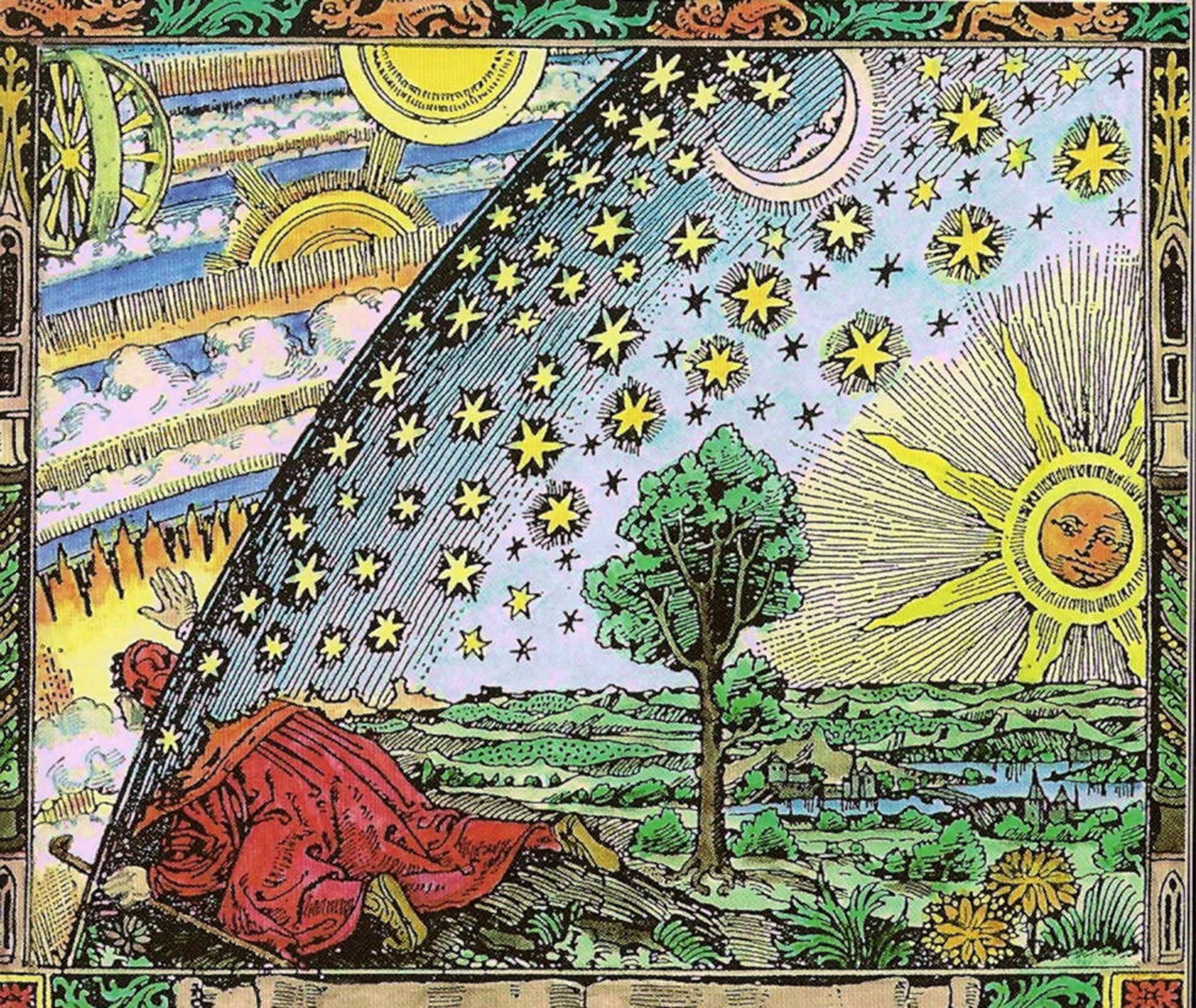

Hamid, a metaphysician and cosmologist, seeks to understand space—primarily, our sense of reality. He investigates abstract questions about the origin, purpose, and destiny of the world and humanity, but comes up against the roadblock of our modern understandings: “The dualistic Cartesian model of reality that separates mind from body and matter from spirituality has dominated our views for so long. These days, we tend to favor scientific explanations and physical explanations.” Hamid believes this rationalistic understanding is missing out on the rich complexity of the world, notably the meaning and value of human experience.

Both philosophers ask in their own way: When place and space are stripped of value, meaning, and connection, can they be recovered?

Our emotional connection to place

McShane seeks to establish a more sophisticated theory of value than what is operative in most environmental discourse. She’s primarily interested in our emotional engagements with place—whether that’s a feeling of love, a sense of respect, or an experience of awe. These different sorts of emotional connections serve as important motivators of environmental values.

McShane explains how these are quite different kinds of connection. Love is just one of many ways we feel tied to a place. For example, we may love a particularly beautiful beach where we vacation frequently. What is the nature of this love, and what happens when that coastline adapts due to climate change? The advantage of a loving connection, McShane claims, is its adaptability and how it “invites an interactive approach that seems premised on change and flux.”

Respect is an altogether different kind of connection and can be more widely shared than love. McShane explains, “You don’t need to be a nature lover or even in nature often to respect it at a certain level,” she says. Importantly, too, McShane shows how an acknowledgement of respect carries certain norms. “We don’t treat things as dispensable, convenient, or merely useful if we respect them.”

Presently, McShane is investigating the power of awe. Awe is experienced in our realizations of the grandeur of nature, such as being wowed at one’s first sight of the Grand Canyon. McShane is researching what these experiences of awe do to us psychologically. “What’s interesting is that experiences of awe—even those that have nothing to with people—inspire more pro-social and less egotistical behavior,” she says.

As a mid-Westerner from the Chicago suburbs, McShane recounts an overwhelming experience of awe she experienced while watching satellite footage of the size and scope of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. “It was really the most astounding thing I’ve ever seen,” she says. While a hurricane is not necessarily a positive experience, the awe it invokes can still bring forth positive and compassionate action. For example, McShane’s institution at the time, North Carolina State University, opened its doors to Louisiana’s college students who were displaced by Katrina’s destruction.

McShane speculates that the overwhelming experience of awe may make one feel small in comparison, and thus, more open-minded and humble. For example, the first photographs of earth taken from Apollo 17 portray the earth as a beautiful yet fragile sphere floating in darkness. The resultant “overview effect”—a profound experience of awe—had a transformational effect on people’s sensibilities and helped to fuel the nascent environmental movement.

However, McShane argues that these emotional responses produce a “mixed bag” psychologically and in how they direct behavior. “A feeling of love invites an interactive approach that is premised on change. However, feelings of respect and awe may provoke a hands-off approach and make one resistant to change,” she says. For example, John Muir’s descriptions and Ansel Adams’ photographs of the American West inspired awe. That feeling became the conservationist rallying cry and a demand for natural areas to be protected and unchanged.

According to McShane, an experience of awe may be humbling, but it may cut off our reflective mechanisms and allow us to be more accommodating. Awe may turn off critical reflection and lead to a giving-in to the instigator of awe, human or natural, rather than a stepping-up to needed action in a given situation. For example, McShane cites the work of psychologists Dacher Keltner and Jonathan Haidt who discuss how awe can produce “passivity, and heightened attention towards the powerful” as well as “reverence, devotion, and the inclination to subordinate one’s own interests and goals in deference to those of the powerful leader.” While an experience of awe may be a good thing for some people, McShane asks, “do all people need more awe? Do all people need more humility? Is our main problem arrogance? For some, yes, but probably not everyone.”

Regardless, this kind of emotional engagement is a dimension of our connection to place to which we should be more mindful. McShane explains that we have different norms for things that we love and connect with versus things that we find useful but from which we are relatively detached: “When we assess value, we don’t capture these differences very well. We need a more sophisticated theory of value to bring to our policy discussions.” McShane is now working on such a theory.

The moral dimension of space

Hamid came to philosophy after following childhood fascinations with science. This began with astronomy, moved to chemistry, and then to an academic pursuit of theoretical physics in college. Hamid explains his journey: “I was always seeking the most fundamental understanding of the world and of space and time, but then I realized that a conceptual framework was needed and that framework was only possible through philosophy.”

Hamid was dissatisfied with scientific explanations of the world that were limited to physical experience or rationalist explanations. “I’m interested in a notion of the ‘world’ that covers the entire gambit of human experience. I’m particularly interested in the development and movement of the world into something better than it is,” he says.

With the support of an international and intercultural upbringing that included Arabic studies, Hamid was particularly drawn to Islamic cosmology and the work of Shaykh Aḥmad al-Aḥsāʾī (1753–1834). Shayk Aḥmad’s work posits multiple levels of the ‘world’ each with its own mode of time and space, similar to the work of ancient philosopher Plotinus. Significantly, Hamid explains, “in Islamic philosophy, there are recognized intermediary domains between the purely natural domain of the senses and the purely intelligible world of rational facts. This intermediary is incredibly more subtle than either world and can account for far more modes of human experience.”

What’s most fascinating and important to Hamid is the way in which value becomes embodied in these more nuanced realms of experience. He describes Hūrqalyā as “a domain of human experience and reality where moral development and corruption take place.” Further, the characteristics of one’s virtue, or one’s vice, are literally on display through one’s bodily comportment. The experience of these realms, Hamid explains, can be “sublime and heavenly, or hellish and gruesome, depending on the moral matrix of the person experiencing it.”

Hamid sums up his investigation of value in Islamic cosmology: “We live in a world of space and time that is utterly devoid of value. Nature, matter, and the body are cut off from spirituality, morality, and the mind. In the realms of Hūrqalyā, all of these beautifully and impactfully come together.”

When asked if he has completed his childhood quest to arrive at the most fundamental understanding of the world, including space and time, Hamid answers, “Yes, but I’ve only recently realized how.” That process, Hamid promises, will be the subject of his next book.