Water color iIllustrations of Clark and Eddy by Jessica McGarity (Graphic Design, '20)

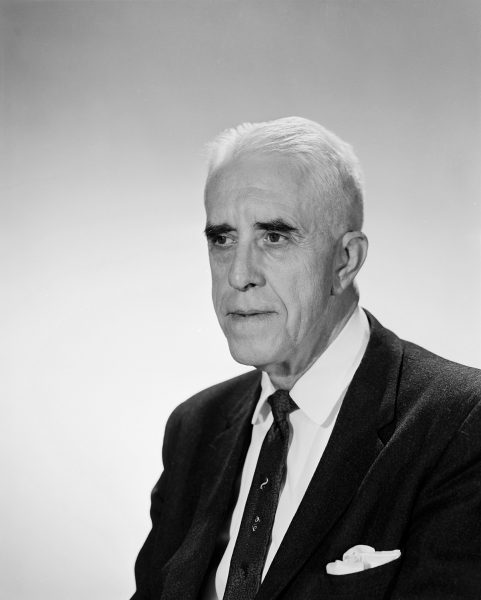

If we had to name just one person responsible for the appearance of Colorado State University today, it would surely be William Morgan. The president of CSU for 20 years (1949-1969), Morgan guided the development of the modern campus, nudging the agricultural buildings further west and then off campus while directing a vast building boom that roared on through the 1960s.

But what buildings? Morgan had been stung in 1957 and again in 1962 by the criticisms from the regional university accrediting body that Colorado State had neglected the humanities and social sciences and had tolerated a “woefully inadequate library.” Morgan looked again at the language of the Morrill Act that had established land-grant institutions like Colorado State, and paid attention to the “liberal” part of the “liberal and practical education of the industrial classes.” His colleague Willard Eddy, founder of the honors program and professor of philosophy, helped the president understand that the liberal arts are fundamental to the work of higher education, offering knowledge and critical thinking skills to all students regardless of their eventual vocation or profession. So before a football stadium and a more modern gym, Morgan insisted on buildings for the liberal arts and a new library.

It is hard to imagine today as students crowd along Centre Avenue Mall, that Clark takes up space once filled by horse and dairy barns, or that a farm implements shed stood where Eddy Hall is.

Building the Liberal Arts

It was Boulder-based architect James Hunter who took Morgan’s initiatives and brought them into being. From 1952 to the late 1960s Hunter designed 25 buildings on the main campus, plus buildings on the Foothills Campus, Rigden Farm, and Pingree Park. Hunter’s modernist style is visible up and down the spine of the main campus, and his handiwork includes Morgan Library, Lory Student Center, the Education Building, the row of residence halls that stretch westward, Eddy Hall, the Clark Building, and Danforth Chapel, where Hunter’s ashes are interred.

A “Liberal Arts” building (renamed Eddy Hall in 1978) went up in 1963, housing at one time or another the departments of English, Philosophy, Ethnic Studies, Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, and Communications Studies.

Eddy Hall quickly became an intensively-used building, not just for liberal arts majors, but for many thousands of other students who took courses to fulfill core curriculum requirements. And, like all heavily-used buildings, Eddy saw a steady stream of Facilities Management staff repairing the heating and cooling systems, replacing furniture, repainting and remodeling spaces.

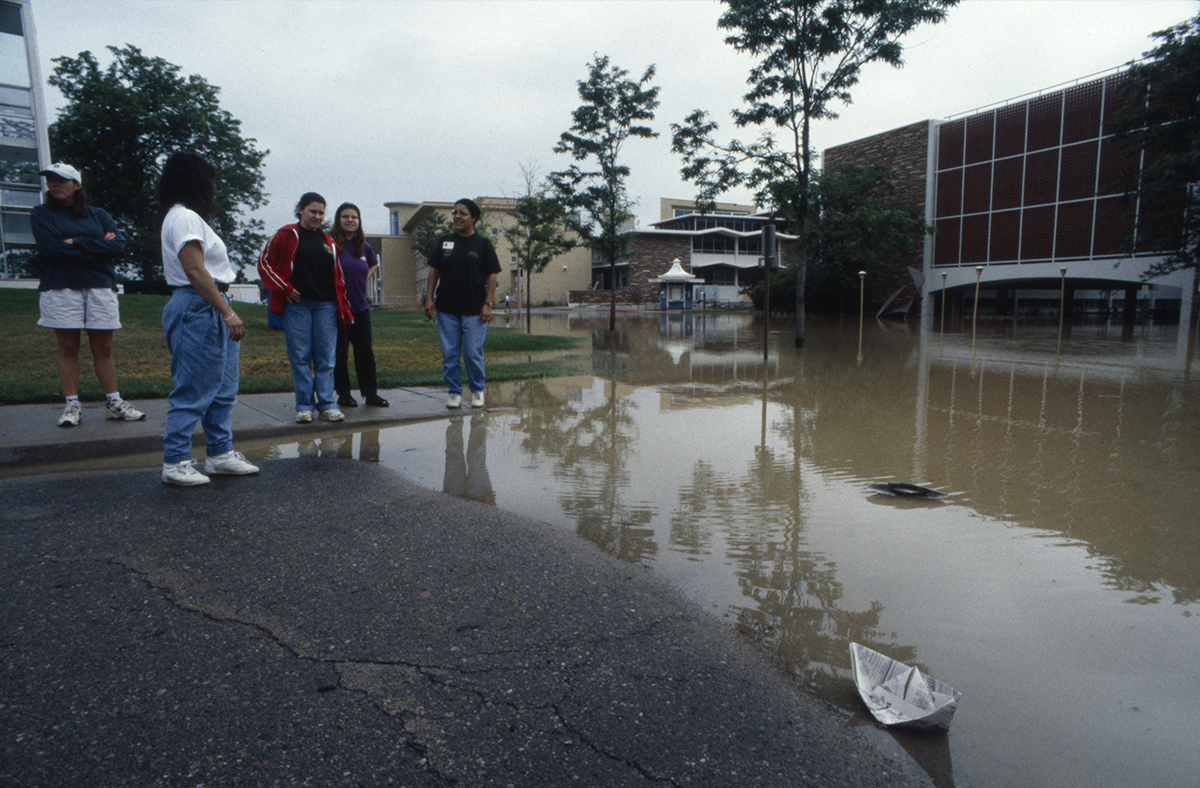

But nothing would compare with the challenge, and the devastation, of the Flood of 1997. Walls of water washed down Elizabeth Street and onto campus, filling up the window wells of Eddy and pouring in through the west-facing entrance. Offices in the lower level were ruined; books, papers, equipment destroyed. The building was patched up enough for the start of classes in August 1997, but clearly the building needed much more attention.

In 2007 the state legislature approved a bond issue for extensive renovation of Eddy, but the Great Recession put a stop to that effort. Five years later, as the economy stabilized, the legislature approved a $7 million issue for mechanical, electrical, and plumbing upgrades, safety and ADA upgrades. In 2013 an additional $4.8 million was approved for a new stone exterior, window replacements, new entrance and plaza, and additional interior work.

But how do you remodel a building that is teeming with students, faculty, and staff on a practically year-around basis? The problem began to be solved when the Communication Studies department moved from Eddy to its new home in the Behavioral Sciences Building (BSB) in January 2014, leaving English and Philosophy still in Eddy.

Originally, the plan called for dividing the remodel project in half, relocating the faculty and staff from one side to the other and then vice versa, but that proved unworkable so everyone was moved to Ingersoll Hall and BSB.

With the building newly empty, renovation proceeded quickly in summer and fall 2014 and into the following year. The building’s architects called for pushing the front façade of the building outward, creating two new large classrooms on the first and second floor and a new entry way, and digging down to create a new mechanical room. As well, the renovated Eddy featured a re-landscaped courtyard, a new University Writing Center, new Eddy Philosophy Library, and several “Eddy’s eddies,” lounge areas just off the main hallways where student gather before and after classes.

Surprising, if not memorable, moments in Eddy Hall

Eddy features a large second-floor amphitheater with an outside stairway off the building’s interior courtyard. The plan was to do very little to that space except replace seating, so there wasn’t as much construction activity back there as in other parts of the building. One day, soon after construction began, a worker found that a door into the amphitheater had been propped open.

Going in, the worker discovered, in the projection booth at the rear, a bedroll and a backpack filled with pornographic videos. Apparently, someone had found his way into the booth and had figured out how to project his prize collection onto the big screen at the front of the room. The next night, the police were waiting for the enterprising fellow as he arrived for his nightly entertainment.

Then, as the project neared completion in spring 2015, a worker replacing ceiling tiles in a third floor office found a stash of vintage Playboy magazines, prompting lots of discussion (and amusement) about whose office that was, and when. What then happened to the magazines, which probably had some collectible value, is unknown.

These stories gave the Eddy remodel a kind of sexy aura; who says humanities people don’t have any fun? The rest of the remodel project went on without more distraction, and the building was officially reopened on August 19, 2015, as home to English, Philosophy, and Ethnic Studies.

Envisioning the Clark Building

For a “Social Science” building, Hunter proposed a complex of two three-story buildings joined by a two-story bridge. In summer 1966, construction began on the B and C wings, with these sections open for use in fall 1967. Construction of the A wing followed and was completed by fall 1968, with a total cost of $5,102,000, the equivalent of about $39,220,000 in 2019. The building was intended to house offices of the departments of History, Anthropology and Sociology, Economics, Political Science, and several units of the College of Business.

The Clark Building sits at practically the center of the “new” (post-Oval) campus, along the spine that runs from Lake Street to the Engineering Building. It is enormous: 252,000 square feet on nearly four acres. It is long and low, and was built to last, made of poured concrete and walls of steel and glass. In contrast to the Eddy Building, which even in its pre-remodel days had a kind of lightness about it, Clark conveys a kind of impassive “thereness.” Hunter’s international style shaped a building that was all about the modern age: functional, serious, cost-effective, a machine for learning. Even the “sun-screens,” horizontal tubes making up huge grids over the second and third floor windows, had a purpose: to deflect heat and light from the intense afternoon sun, although they were quickly derided as “wine racks” or “pigeon roosts.”

Clark quickly became a “workhorse” of a building on the main campus, serving students not just in the liberal arts disciplines, but from across virtually all majors and classes.

By the early 2000s the building was showing its age. The university and the student facilities fee board (UFFAB) invested $6,000,000 between 2006 and 2013 for upgrades to auditoriums in the A wing and general assignment classrooms in C. The College of Liberal Arts and UFFAB contributed funds for office and classroom renovations in Clark A basement in 2017-18. But the building needed more intensive work to fix its electrical and plumbing systems, its outmoded security systems, its lack of fire suppression systems. And students began to complain about its gloomy interiors, narrow one-way staircases, out-of-the-way elevator, lack of wayfinding, the misalignment of the B wing with the A and C wings.

An article in the Rocky Mountain Collegian in 2015 was titled, “Clark C is just the worst.” Two years later, a student group, Rams for Representation, released a YouTube video spotlighting the overall shabby condition of hallways and stairwells and the presence of asbestos in Clark C.

What to do? In 2016, a new liberal arts dean, Ben Withers, set about making a case not for just another needed fix-up of the Clark Building, but for a thorough and forward-looking “revitalization” of the building.

Since the liberal arts forms the core of a university’s mission, as Morgan and Eddy argued in the middle of the twentieth century, and since the Clark Building sits at the center of campus, then it should be a “gateway” building for education into the twenty-first century. A revitalized Clark could move beyond the transactional, where people simply come to do the business of teaching, learning, and scholarship, and instead become transformational, where knowledge and lives are enriched for the common good.

A long series of meetings has followed the dean’s decision—all in an effort to hear and refine ideas toward a new vision for the building. What will liberal arts education look like in the twenty-first century? How should the building make that education, and the scholarship that supports it, possible?

About the author

Bruce Ronda is special projects analyst for the College of Liberal Arts. He is an emeritus professor of English and was associate dean (2012-2017) in the College during the Eddy remodel.