As of January 2019, we are 10 years from the original introduction of Bitcoin, the most recognizable cryptocurrency currently available. A digital currency that uses cryptography for security, cryptocurrency (and specifically, Bitcoin) operates peer-to-peer and without the authority of banks, allowing people to directly pay and receive payments without third party intervention. As we move toward more digital lives, and as technology increasingly becomes a part of our daily routine, we must begin to ask ourselves about the role of these advances in our lives and if they will help or hinder humanity’s progress.

In 2008, the creator of Bitcoin, the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto, published their paper “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” to a cryptocurrency mailing list, and in early 2009 released the first Bitcoin software. The first recorded transaction of Bitcoin occurred in 2010 when developer Leszlo Hanyecz paid 10,000 bitcoin for two pizzas, an amount of bitcoin that today would be worth $100 million. In the years since that transaction, Bitcoins have increased and decreased in value, survived the hacking of the largest Bitcoin exchange, Mt. Gox, have been lauded as the future of money, and condemned as the next greatest scam. In the discipline of ethnic studies, interest in cryptocurrency lies in its potential within the international development sector: does cryptocurrency have the potential to be an economic equalizer or will it be another bandage for a problem too large to fix?

In Kenya, for example, in the last decade or so, the push in the development sector has been toward the economic system of microbusinesses. Often the target of these endeavors are women in the rural areas of the country who receive loans from a larger organization to start a business. For many of these businesses this model is a way for them to access an international community of potential buyers.

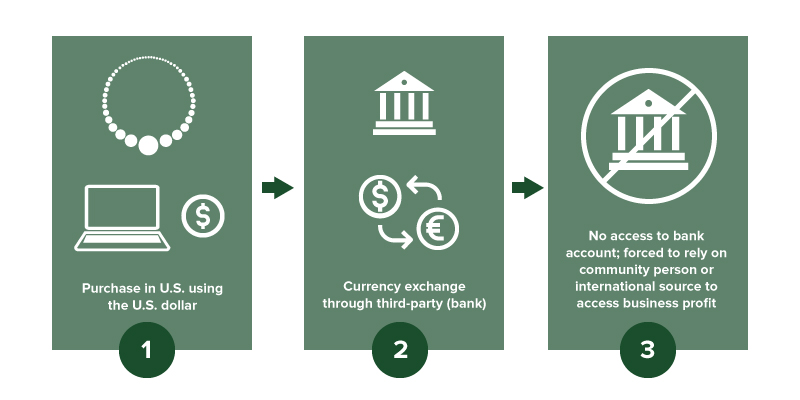

Take, for instance, a group of women selling beaded jewelry who must utilize a third party in order to exchange money. An individual in the U.S. can purchase a necklace through a website and the money is transferred, but it must first go through a third party to exchange the money: someone must have access to the bank account through which the money is being accepted. Once through the bank, money is given to the business itself. Problems arise when the women who are running the businesses do not have access to a bank account and therefore rely on someone within the community who does, or an outside, often international, source.

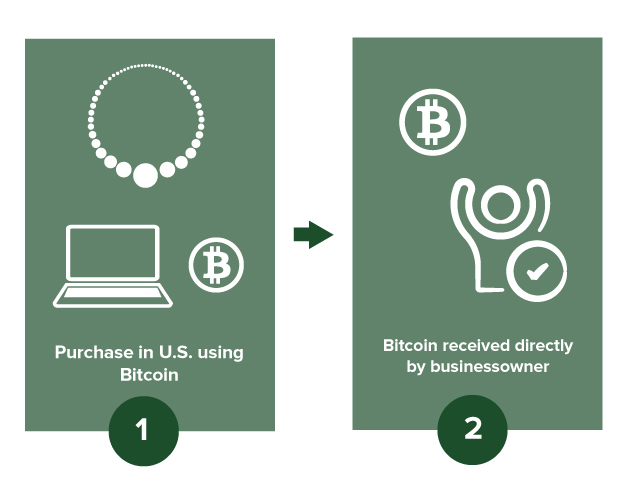

The use of Bitcoin alleviates this problem by eliminating the third party: someone who is ‘banked.’ The cryptocurrency allows for a peer-to-peer transaction to take place, and the money is exchanged directly. These transactions are borderless, secure, private, fast, and require little tech skill or background. Anyone with access to a cell phone has access to the direct transfer of funds, and therefore more control over the finances and business itself. There is currently no large-scale usage of Bitcoin in Kenya, however, the opportunity for usage exists countrywide, especially in rural areas where the direct exchange of funds outside of a formal economy could facilitate increased participation in the local market in addition to controlling the potential for corruption.

In many countries in which there are already ongoing development projects, the use of Bitcoin allows the people of the country to access a financial system that is not in the control of their government. The set number of Bitcoin that will ever exist, just under 21 million, will never change; it is free from the market of inflation or deflation, which has the potential to stabilize economies that are rife with inflation issues and corruption. The database itself operates as a blockchain where information entered into the system is permanent and verified through mathematical equations: it is immutable. It eliminates the issues of trust when there is a necessary third party person to validate all entries within the database.

Bitcoin, however, does not fit as a cure-all to the issues of development. To be involved in the process beyond the peer-to-peer exchange of funds, a person (or company), would need to be involved in the mining process of the coins. The currency functions through a system called ‘proof of work,’ which rewards miners for completing the mathematical equations necessary in the blockchain to verify data. At this point in the cryptocurrency’s life, the amount of money that is required to mine Bitcoin puts it far beyond the reaches of the average person, let alone someone without access to a bank.

The majority of mining is now done on server farms, large complexes in remote regions. In China, for example, Bitmain runs one of the largest server farms, with approximately 25,000 machines, running billions of equations, and employing about 50 people. And the environmental toll of Bitcoin mining could be disastrous; the amount of electricity needed for one Bitcoin transaction is the same as powering approximately 10 houses for an entire day. Server farms must maintain a constantly cool environment to avoid the machines from overheating as they consistently work through equations. Often these facilities run on coal, requiring immense amounts of energy, and increasing their environmental impact. Environmentally, we as the collective 7.5 billion people on this planet must already contemplate the role of our energy usage in relationship to a warming planet and the politics intricately tied to it. If the ‘developed world’ is already using the majority of energy resources on the planet, while simultaneously clamping down on border security, does a consistently increasing usage of electricity have the potential to increase climate refugees and the need for development solutions?

Overall, we must begin to ask ourselves if the use of Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies truly opens the broader world economy for people in developing countries, or if that increase in participation is at a superficial level akin to microbusiness, allowing for participation but not for structural change. If the same people who are rich remain rich and the poor remain poor, but with slightly increased access to the economy, does that provide enough of an access for people to move beyond the need for development projects? Alternatively, does Bitcoin provide another bandage for a system that needs to be structurally changed at its core to address wealth distribution?

As additional cryptocurrencies emerge and different blockchain platforms become more popular, the question of if we can make cryptocurrency and blockchain work within the development sector will transfer to how will we make them work within these systems. A new type of economy is emerging and we should be careful to ensure its productive use for everyone.