At the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art, art and technology continually intersect. The Spring 2019 exhibition, Off Kilter, On Point: Art of the 1960s from the Permanent Collection, encapsulated ways in which technology and art are interrelated by featuring the decade where that idea came into focus.

Lynn Boland, director and chief curator of the museum explains. “The history of art and the history of technology are completely intertwined,” he says. “We have an ancient Roman marble bust [in the museum's collection] but in addition to all of the technological advances in quarrying and carving marble, the Romans’ invention of cement and the uses that that is put to — it's simply astonishing.”

The impressionist art movement also responded to technological advancements; the late 19th century French style would have been impossible without the invention of paint in tubes and portable easels, which allowed artists to go out into the landscape.

“19th century French philosopher Auguste Comte argued that truth is verifiable through observation, an idea that artists of the era were able to incorporate into their practice thanks to technological advances,” explains Boland. “But it's not just technology serving art, it really goes both ways.”

Minimalist visionaries

In the exhibition, the first object patrons saw upon walking into the Griffin Foundation Gallery was the large-scale electromagnetic sculpture by Panayotis Vassilakis (Takis).

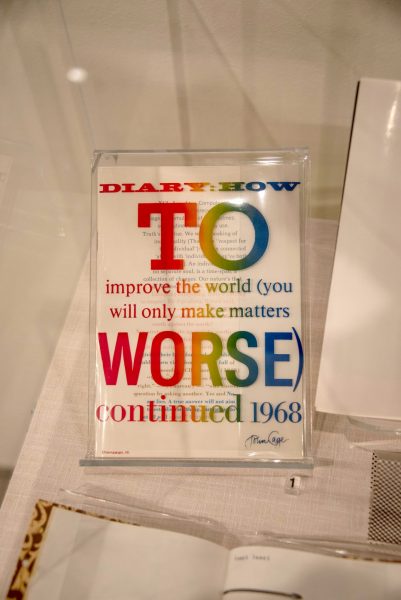

Boland finds the work exciting because it uses simple forms for expressing the invisible and complicated forces of science and technology. “That's the most obvious example of the use of technology from the exhibition, but there are just so many others.” Boland’s reference includes sound works by Marcel Duchamp (7” inch vinyl record), quarter-inch tape produced by Bruce Nauman, and even less obvious, John Cage's How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) continued, printed on clear mylar, a very new material at the time.

Similarly, artist Bridget Riley experimented with printing on acrylic, another new material in the 60s. “The printing technique provides a different kind of surface and provides a different appearance to the work that simply wasn't possible before this,” Boland states.

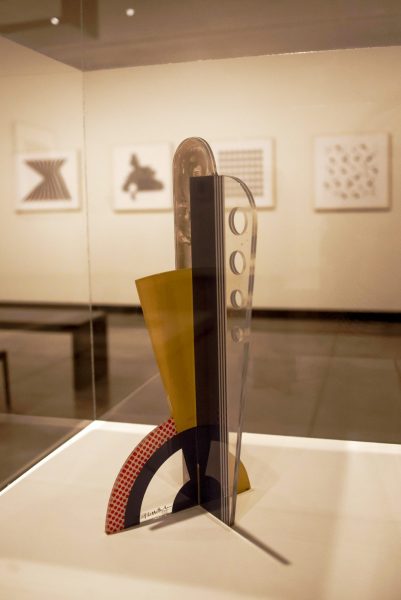

The exhibition also featured a 1968 Roy Lichtenstein on clear acrylic with embedded reflective mylar. Boland shares an appropriate quote from the 1967 movie The Graduate. “’I want to say one word to you. Just one word. Are you listening? Plastics.’ This was cutting-edge stuff!”

For Boland, however, the work within the exhibition that best illustrated the real inter-relationship between art and technology was De Wain Valentine’s Red Top (1966). Born in 1936 in Fort Collins, Valentine attended high school in what is now the University Center for the Arts. He was a rock hound as a youth, collecting gems and minerals along the Front Range. While polishing rocks to make jewelry in shop class, Valentine was introduced to polyester resin, which was surplused in large amounts by the military to high schools after WWII.

As Valentine learned to mix and cast resin, he was inspired to continue his artistic studies at the University of Boulder. After relocating to Venice Beach, California, his abstract art was part of the West Coast Minimalist movement, which later became the Light and Space Movement. At the time, minimalism was responding to philosophies of phenomenology and many artists were looking to make human-scale work, something that became intensely important to Valentine, even though the plastics industry said it would be impossible to accomplish with the medium.

The act of mixing the catalyst in the base material creates a very hot chemical reaction, which increases as larger volumes are mixed. Despite nearly burning down his studio, Valentine refused to give up and ended up discovering a process for creating large-scale polyester resin-cast sculptures, a mixture he was able to patent as Valentine MasKast Resin, marketed by Hastings Plastics.

“As Valentine made increasingly large, even monumental, sculptures, he was able to realize his vision; his way of doing it was then used by other artists,” Boland says.

Another of Boland’s favorite examples is how artist Fujiko Nakaya, as part of the group “Experiments in Art and Technology,” created her cloud sculpture around the Pepsi Pavilion at the 1970s World Fair in Osaka, Japan. Nakaya worked closely with international engineers to design a nozzle capable of spraying a very fine mist of water. The technology is now used in crop frost protection and for outdoor misters.

“To me, these are really inspiring stories of the way in which artistic experimentation contributes to our society. I hope what came out through the exhibition texts and interpretations is the newness of some of the things that we take for granted now, but also how exciting, fresh, and alive these things can still be.”

— Lynn Boland

Future technology and the museum

The Gregory Allicar Museum of Art is dedicated to representing current technology and explores ways of including more new media, such as virtual reality, in its galleries. “It’s essential that we stay up-to-date on new technologies, both their artistic uses and their use for education,” Boland says.

Media has life and significance beyond the moment it's created but in terms of newness, or novelty of the technology, keeping pace is increasingly an issue in the relative time frame of museums as shows are conceived and curated years in advance.

“2015 was the first time I was able to use augmented reality technology in response to a work of art, and it was a really cutting-edge thing,” remembers Boland. “I don't think it was even a year until Pokémon GO came out and the exact same technology was on every kid's phone.”

The museum is certainly not looking to replace traditional art, or approaches to interpreting it, as museum methodologies rely on very old-fashioned ideas of connoisseurship, brought into the 21st century with digital technologies.

“What we do and what the humanities do is maintain the past, but we are always adding new tools to help us understand it,” says Boland. “That’s what excited me about the work in Off-Kilter and about the work we're looking at bringing into the museum going forward."

Off Kilter, On Point was on display at the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art Jan. 22 through April 13, 2019.

Coming Soon

Coming in Fall 2019, the exhibition, Moon Museum: Unofficial Art on Apollo 12, is another wonderful example of the ways in which technology and art are inter-related. It will feature a version of the chip that traveled with the Apollo 12 lunar lander to the moon. The tantalum nitride film on a ceramic wafer, produced by Bell Labs in 1969, features six small drawings by Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, David Novros, John Chamberlain, Claes Oldenburg, and Forrest (Frosty) Myers, the organizer of the project.