This article includes content from a College of Liberal Arts white paper written by Dr. Ben Withers, Dean, and Dr. Michael Carolan, Associate Dean.

While it has become popular recently to question the value of not only a liberal arts education, but higher education in general (the expense, the time required, and the uncertain career outcome), colleges and universities have a need and an obligation to tell the public about the value they bring to individuals personally and to society at large.

A college education not only provides an individual with high-level knowledge and inquiry methods, but also a practical sensibility to apply that knowledge to the complex problems people face every day. Problems such as health and safety near fracking sites, music teacher identity and training, or public discourse about important political or municipal issues.

In addition, higher education provides students an opportunity to learn and engage with the knowledge and the community on those everyday issues, giving students a realistic sense of how to apply their class work to the world.

A 1999 Kellogg Commission report suggests:

“... the new questions before us involve not only important issues requiring the application of hard data and science, but challenging, and frequently fuzzy, problems involving human behavior and motivation, complex social systems, and personal values that are controversial simply because they are important.”

We believe that the disciplines contained within the College of Liberal Arts – spanning the humanities, social sciences, and visual/performing arts – will be key in addressing crucial issues and enhancing the quality of life of the diverse people of Colorado, the nation, and the world.

One of the ways that we address those crucial issues is through engaged scholarship. Engaged scholarship is both a process and an outcome; it’s a way of generating new knowledge and new solutions that involves both the university and the community. Critical to the process is the relationship between the two entities: engaged scholarship relies on the community to identify the need or co-create the questions alongside our CSU faculty and students. In this collaboration, the two – university and community – co-create the knowledge, and that relationship of reciprocity is an exciting and transformative way of having a direct impact.

For the College of Liberal Arts, the results of that partnership, and the information gained, problem solved, or creative work produced, adds to the literature and knowledge base of our faculty members' fields, thereby continuing to spur research, discovery, and new knowledge. The information or solutions generated don’t stay on library shelves but rather are disseminated across the community and shared with others who are looking to address similar concerns.

Read below for a few examples of how we do engaged scholarship in the College of Liberal Arts.

- Fracking & Quality of Life; Rocky Flats Health Study (Sociology)

- The Center for Public Deliberation - Facilitating and Improving Public Discourse (Communication Studies)

- Local Economic Development and Local Sustainability Policy (Political Science)

- Peer-Assisted Learning, Teacher Training, and Teacher Identity Development (Music)

- The Community Literacy Center - Alternative Literacy Opportunities for Underserved Populations (English)

Examples of Engaged Scholarship in the College of Liberal Arts at CSU

Stephanie Malin, Assistant Professor, Sociology

Dr. Malin works on issues of natural resource extraction and privatization, environmental justice and health, and energy production and quality of life, using “participatory action research” where participants help design and implement the research process, while being meaningfully involved in the study throughout the process.

Dr. Malin works on issues of natural resource extraction and privatization, environmental justice and health, and energy production and quality of life, using “participatory action research” where participants help design and implement the research process, while being meaningfully involved in the study throughout the process.

Fracking & Quality of Life

Via a grant funded by the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Malin and team have worked for nearly four years with three groups from Windsor, Greeley, and Fort Collins on a project that looks at the relationships between living in a region with intensive unconventional oil and gas development, quality of life, and stress levels.

The social science team, led by Dr. Malin, conducted partner-reviewed surveys of the three communities while epidemiologists took hair samples, cheek swabs, and blood to measure biomarkers of stress. Through two independent study courses and internships, eight graduate students and three undergraduate students assisted with surveys, with two students extending their work over the summer to analyze data and write a manuscript that came out in 2017. Partners helped host community meetings through all stages of design, implementation, and analysis of survey and biomarker data. Students continue to work on this project, helping code interviews, work with community members on PhotoVoice projects, analyze survey data, write manuscripts, and assist with interviews.

Because of the long-term, sustained relationships they’ve made and reputations they’ve developed, Malin and team are regularly invited to speak to groups throughout northern Colorado – such as school PTAs – who want to know what to consider when well pads are proposed near schools or neighborhoods.

“Understanding what needs to be done in the community and what’s useful for people – that drives a lot of the research I conduct,” Malin says.

Candelas subdivision near the buffer zone of the Rocky Flats Health Study site. Photo by Stephanie Malin.

Rocky Flats Health Study

The Rocky Flats Health Study is a community-driven study to look at the long-term environmental and public health outcomes of living near the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant, which produced 70,000 plutonium triggers for nuclear weapons before it was closed. Dr. Malin organized a team by combining her efforts with researchers from Metro State in Denver – nursing professors, soil scientist, statisticians, and members of concerned community groups such as Rocky Flats Downwinders. They co-developed a survey instrument to gather descriptive data that showed evidence of rare cancers in the area.

Currently, community members report their personal oral histories to Malin and two graduate students, who are documenting their rare cancers or multiple unusual diagnoses as the team searches for funding to support a more robust community-based health study. While the CDPHE has also conducted studies assessing the health impacts of the Rocky Flats site, they’ve used state-level data from Colorado’s cancer registry. Community members have requested a study that actively collects data from the community using more mixed and ethnographic methods, which makes it a community-based health study “because that’s what the community wants,” Malin says.

While this project has been only minimally funded by sources like the American Sociological Association’s Spivack Community Action Grant and support from nuclear geographers at University of Southampton in the U.K., the project continues because of the interest of the students. “They’re really driving this. They’ve become super engaged with the communities themselves and represented the project when I can’t be there.”

Martin Carcasson, Professor, and Katie Knobloch, Assistant Professor, Communication Studies

CSU Center for Public Deliberation

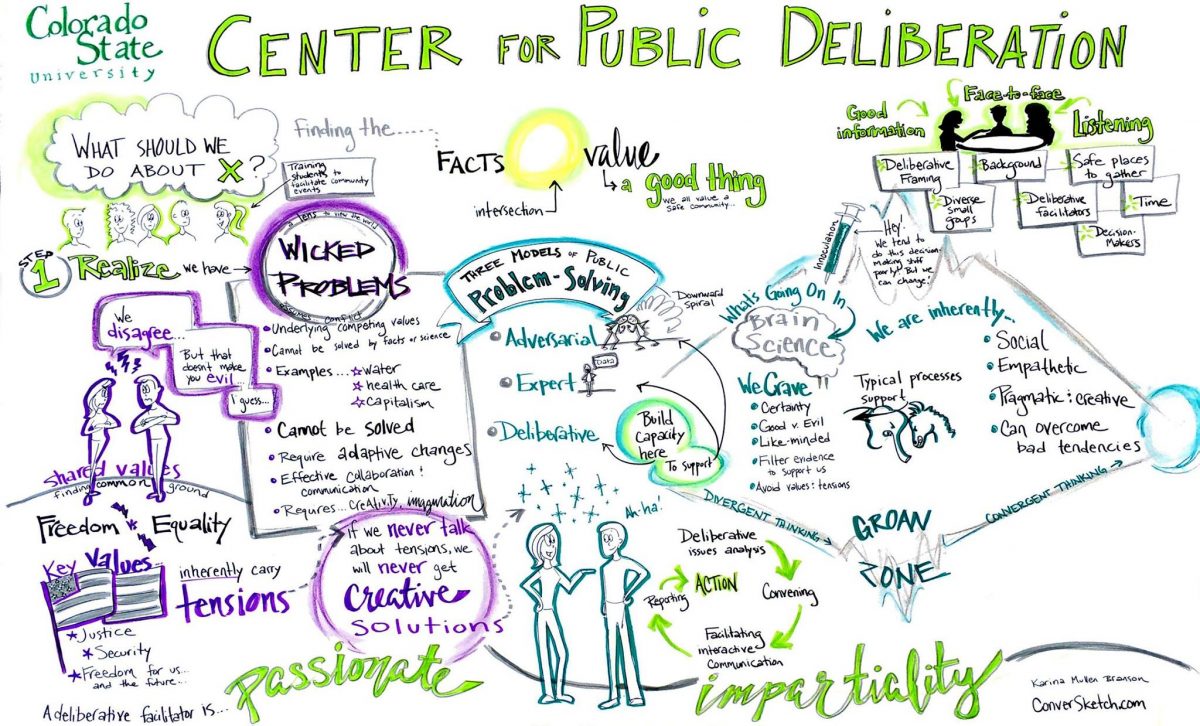

As director and associate director of the Center for Public Deliberation, whose mission is to enhance local democracy through improved public communication and community problem-solving, Drs. Carcasson and Knobloch have created a space and training ground to improve the way our community is able to engage complex issues so that we arrive at better decisions and build a stronger community.

The CPD is an interdisciplinary organization and recruits exemplary students from across disciplines, including biomedical science, business, psychology, history, and more. Working with Carcasson, Knobloch, and CPD Program Coordinator Kalie McMonagle, every CPD student receives a semester of hands-on training to help them understand the deliberative process and become skilled small group facilitators. Once students complete their first semester, they return to complete practicum hours where they facilitate meetings connected to local projects.

The CPD assists local governments, schools, and community organizations in addressing key local issues. Deliberation requires productive spaces for citizens to come together, good and fair information to help structure the conversation, and skilled facilitators to guide the process. This means the CPD starts by researching and developing useful background material. Then they work with partners to invite those affected by the issue into the room. Students then guide participants through these sometimes difficult conversations in small groups. From designing to facilitating to reporting on innovative public events, they rely on contemporary, relevant research from the fields of deliberation and communication studies. “Democracy requires high levels of connection and quality communication, and that doesn’t happen naturally. We work to elevate the conversation about ‘wicked problems,’ dealing with the tensions between values that don’t have a technical solution,” says Carcasson.

At the CPD, all of the projects are also ongoing experiments to improve how to design, run, and report on innovative public engagement processes. The CPD’s engaged research is focused both on the issues addressed as well as the deliberative process itself. Carcasson, for example, has published on the role of experts, the role of centers like the CPD in a local community, and the importance of process design that avoids triggering the negative quirks of human nature. Knobloch’s research focuses on the assessment of deliberative processes, and how the processes work to create a more informed and engaged citizenry.

Susan Opp, Associate Professor, Political Science

Dr. Opp is considered a “pracademic” – someone that spans the boundary of the academy and practice – involved with local governments and federal partners on issues of local sustainability and economic development.

Dr. Opp is considered a “pracademic” – someone that spans the boundary of the academy and practice – involved with local governments and federal partners on issues of local sustainability and economic development.

The topics of her last two books were local economic development and the environment, and performance measurement in local sustainability policy. Both of these books included contributions by practicing public servants from all over the country writing about their experiences on the topic.

Through these research partnerships with more than a dozen public servants, on research as well as “concepts in action” cases based on their specific community’s strengths and experiences, Opp was able to study and address community issues while also providing a venue for the public sector partner to highlight their successes and innovations to a broader audience in a way that is not usually possible (and which allows for engagement with scholars and other practitioners around the country). This type of co-produced research allows for policy innovations to rapidly diffuse and provides a way to translate the most recent academic knowledge into practice.

Alongside the research engagement, Opp also works on partnerships focused on students. Through service-learning projects in courses, students are able to engage with public sector partners who act as clients so that the students may conduct research and propose policy solutions, providing much needed resources to the public service partner while also allowing the student to practice their own research and policy skills. Alongside the service-learning projects, Opp has worked to create a robust local government internship program that has helped dozens of students gain practical experience in the public sector while providing the public sector sponsor with much needed assistance from the students of CSU.

“We do research to solve a problem and make life better for people,” Opp says. The growing divide between scientific research and practice is concerning. Focusing research, teaching, and service on problem solving with an externally focused perspective allows the science to make the world a better place.

Erik Johnson, Associate Professor, Music, Theatre, and Dance

Through the Middle School Outreach Ensemble (MSOE) and the Trying-on-Teaching project, collaborative, peer-assisted learning, teacher training, and teacher identity development happen.

Oriented toward a social justice mission, and to remedy the national shortage of qualified licensed K-12 educators, the Middle School Outreach Ensemble (MSOE) aims to

(a) encourage highly qualified pre-college students to consider a career in education,

(b) sustain active community engagement for undergraduate music education majors,

(c) provide a low-cost, high-impact collaborative instruction for local middle school music students, and

(d) disseminate research and best-practice data related to collaborative learning models and teacher resilience gathered via empirically-designed inquiry.

Over a period of three months, students from the region in middle school band or orchestra programs receive instruction in ensemble rehearsals and individualized attention in small-group sectionals. Rehearsals are taught by CSU faculty, community master teachers, undergraduate and graduate music education majors, and select high school band students. The program concludes with a concert in the Griffin Concert Hall at the University Center for the Arts at Colorado State University.

This Trying-on-Teaching component of the curriculum allows high school students to make decisions about their potential course of study in college. Additionally, the program provides teaching, conducting, and composing experience to current CSU students as they immediately apply classroom instruction in a meaningful, supervised environment.

"MSOE @ CSU brings together all aspects of the instrumental music education community. From retired teachers to aspiring young educators, MSOE is an engine that drives innovation in teaching practice and music education scholarship through empowering individuals to have a voice in how we can change lives through the art of music-making," says Johnson. "Research garnered from this program has been presented on a range of international and local stages. However, it is the local impact that is most tangible: I stand with awe each Wednesday night when I witness the intention, professionalism, and passion that the 300 students and teachers of MSOE 2018 bring to their interactions to realize our 2018 social justice theme Playing it Forward. They are changing their world for the better right before our eyes..."

Tobi Jacobi, Professor, English, Director of the Community Literacy Center

The Community Literacy Center (CLC) in the Department of English provides alternative literacy opportunities that work to educate and empower underserved populations through community-based writing programs. The CLC partners with youth rehabilitation centers, the local jail, and community corrections to offer seven SpeakOut! creative writing workshops each week of the semester.

Literacy – functional, critical, and creative – is integral to successful participation in civic society and lies at the heart of the goals for these community-university partnerships. These partnerships address the challenge of literacy fluency and identity perception through three modes of engagement: work with individual writers, sponsorship of supportive writing communities, and the creation of popular and scholarly publications.

Since 2005, thousands of community writers have participated, and more than 1400 have chosen to publish more than 3000 pages of writing. In addition to literacy skills, the act of writing and publishing builds self-confidence, improves peer and familial relations, and helps confined individuals imagine strong futures for themselves in our communities. One writer reflects that “SpeakOut has helped me to be able to express some of the feeling of my mother’s sudden death. I believe SpeakOut is one of the best programs we have here in that it allows us to express ourselves; it also encourages us to express ourselves without fear of getting in trouble or being belittled for our feelings.”

CSU students and volunteers benefit from alternative teaching experience, career preparation, and application of classroom knowledge. They received the CSU 2018 Exceptional Achievement in Service-Learning Student Award, a collective honor that many students wish they could share with writing participants. As one student notes, “Sometimes I wonder who the workshop is really for, and then I am reminded of how thankful I am that I am just the facilitator, a role I think is more equal than teacher or instructor. And I don’t feel guilty about needing this workshop just as much as the confined writers need it.”

Together, CSU faculty, interns and volunteers collect and present data (surveys, interviews) that honors voices/contributions of community participants, working to write with rather than about them whenever possible. This has led to the distribution of 1000 copies of the SpeakOut Journal annually and research and engagement opportunities for CSU students and faculty; emerging research has appeared in 14 journal articles and book chapters and has been reported at over 50 national/international conferences.

“We believe that we participate in literacy activism and contribute to a more socially just world through the circulation of stories that are joyful, alarming, and sometimes difficult to hear. This is the work of building a better world together,” says Jacobi.