In late August 2017, Hurricane Harvey dumped more than 50 inches of rainfall in many parts of Houston and southeast Texas. The storm broke records for the most significant rainfall event in U.S. history and produced catastrophic flooding and damage that people are still recovering from more than a year later.

CSU cultural anthropology professor Katherine Browne is investigating the impacts of this disaster among people across six counties in and around Houston and southeast Texas.

Browne and her colleague, Caela O’Connell of the University of Tennessee, have received more than $120,000 from the National Science Foundation to conduct a two-year collaborative study of the factors that influence decision-making when people in different socioeconomic groups face disasters.

“Every disaster imposes a lot of new decisions on survivors,” Browne said. “If you’ve ever had to move to a different home, you know the exhausting number of micro-decisions you have to make. I think we sometimes forget about that kind of exhaustion during and after a disaster. It’s a hundred times worse and all happens in the midst of profound loss with no upside in sight.”

A novel decision-making study to examine risk and interdependencies

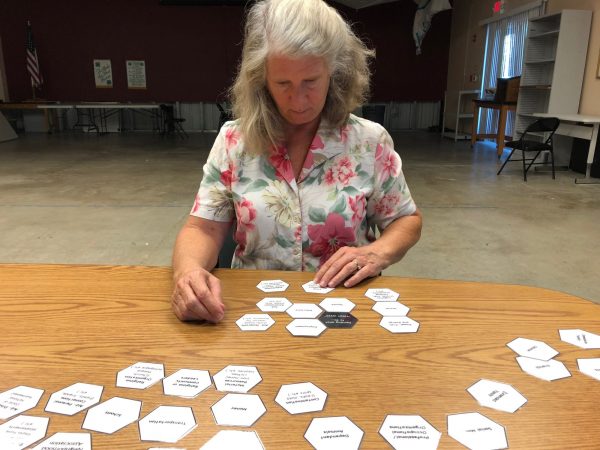

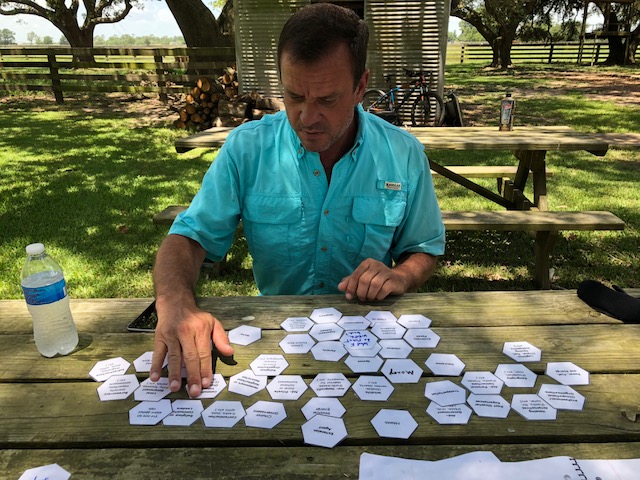

Since the storm, Browne has made five trips to southeast Texas to test the new approach that she developed with O’Connell. Their research involves applying “assemblage” theory to decision-making research. In this approach, each respondent identifies the influences shaping key decisions from a selection of more than 50 tiles that span social, economic, psychological, environmental, and bureaucratic-related issues. For each decision, the respondents build their own “assemblage” of relevant tiles (using blank tiles to create any new factors not included in the set). The process draws out respondents’ own stories, providing holistic data that can be distilled and compared across the sample. Such a context-rich, comparative approach to studying decision-making is rare.

What Browne has documented so far is striking. As an example, some of the ranchers she has worked with have taught her that preparedness means training your cattle to move to different pastures regularly in order to be disaster-ready. So, when you learn a hurricane is coming or a flood threatens the herd’s safety, they already know the drill. In this way, decisions can be straightforward and planned in advance — except when flooding exceeds expectations by several feet, as it did during Harvey.

The epic flooding required some ranchers to move cattle to areas they’d never been, and onto property that wasn’t theirs, in order to survive. One rancher explained that his decision got complicated when he realized he needed a pilot and a plane to locate the closest high ground to save his cattle. He had to lean on a friend to supply these resources and used Facebook to rally others to bring airboats to deliver hay to the stranded cattle.

In this case, the factors impacting his decision about what to do in the first days after the event included tiles like “social media,” “nutrition for cattle,” “specialized resources,” and “friends of friends,” among many others.

In the city of Houston, Browne interviewed a woman whose family home was flooded with several feet of water. There was so much mold damage that the walls had to be stripped down to the studs: except for the walls in the dining room. The woman insisted on preserving that space because it was where her family had for generations enjoyed long conversations and entertained company. In all of the loss, this decision helped her hold on to a material reminder of her family history and gave her a way to make her renovated space feel like “home.” Her decision included tiles like “ancestors,” “larger family,” “faith,” and “attachment to place,” among others.

These and other cases begin to make clear the complexities involved in an apparently straightforward decision. They also make clear how much interdependencies (for example, on people, on animals, on the state) influence the choices people make.

A landscape of risk

Exacerbating the effects of what is known as Harvey’s “rain bomb” was the Houston area’s economic reliance on the petrochemical industry.

“The intersection of risks in the Houston area is complicated,” Browne said. “It’s not just hurricanes, which are, of course, made worse by climate change and sea-level rise. It’s also the risk of significant petrochemical exposures.”

Oil refineries, natural gas facilities, and chemical plants, along with their associated 100-yard-long storage tanks, pose troubling risks when there is a storm surge like the one caused by Hurricane Harvey, Browne explained. During Hurricane Katrina, for example, a storage tank breached at a petroleum refinery in St. Bernard Parish and leaked more than one million gallons of oil, contaminating 1,700 homes in the area. During and after Harvey, there were more than 100 toxic releases in the form of spills, leaks, and explosions that discharged significant quantities of toxins into the air, water, and soil.

“It’s very sobering,” Browne said. “Houston has 6.3 million people, historically lax zoning, and a grow-at-all-costs mentality. It’s also the petrochemical capital of the United States. These are all significant compounding risk factors, making it even more urgent to understand how people account for these factors in their decision-making.”

Misleading flood maps and miscalculations

Another factor that made Harvey so serious, she said, is the fact that many of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s floodplain maps were out of date. In fact, nearly 75 percent of the 204,000 residences damaged from flooding in Harris County, where Houston is located, fell outside the federally regulated 100-year flood plain. And, since people don’t often purchase flood insurance if they’re not in a designated floodplain, that left tens of thousands of homeowners uninsured and unprepared.

She added that overdevelopment contributed to the danger of the situation. When water rose and spilled over reservoirs’ banks, it inundated residential areas in places where planners lacked the foresight to create infrastructure that could handle such a large amount of water.

“The flooding is a byproduct of the development ethic and the lack of political will to see the interaction of various factors,” Browne said, adding that the area’s commitment to growth has undermined its adaptation to risk. “Entire new subdivisions were ruined.”

Understanding disaster-impacted communities to reduce suffering

Based on her 13 years of experience, working first with the aftermath of Katrina in 2005 and now with Harvey, Browne’s future plans include creating the nation’s first-ever Ethnographic Field School for Risk and Disaster on the Texas coast.

Browne’s four-week ethnographic field school for undergraduates will debut in summer 2020. The Field School is a collaboration between Colorado State University and Texas A&M Corpus Christi, where students will be housed. Browne will lead classes and direct students’ original research projects. Field school participants will interview and map risk perception among residents from coastal towns and urban areas, as well as farming and ranching communities. Results might be used in developing new risk reduction strategies. The Field School effort folds undergraduate study into Browne’s larger vision for changing how disaster-impacted communities are understood by agencies and organizations attempting to help. In 2016, she and O’Connell spearheaded the creation of the Culture and Disaster Action Network (CADAN) to bridge the work of academics and practitioners and help ensure that local knowledge and attention to cultural and historical context can nurture resilience and promote successful recovery for communities impacted by catastrophe.

“There are layered realities of the risk landscape,” Browne said. “I don’t relish uncovering all this, but I’m motivated by the importance of it.”

“Our goal is to understand the context of cultural variation by grasping how different people think about risk, interdependencies and place-attachment, then moving that knowledge into practitioner realms can help reduce unnecessary suffering.”

Prof. Katherine Browne

Katherine Browne has been named winner of the prestigious Franz Boas Award for Exemplary Service to Anthropology, joining a list of previous winners who are counted among the giants of the field. It's the 'Nobel Prize for anthropologists.'