Photo: The Big Thompson River thunders through the east edge of the Big Thompson Canyon creating a large waterfall Friday September 13, 2013.The flood damaged sections of Highway 34, at the left.

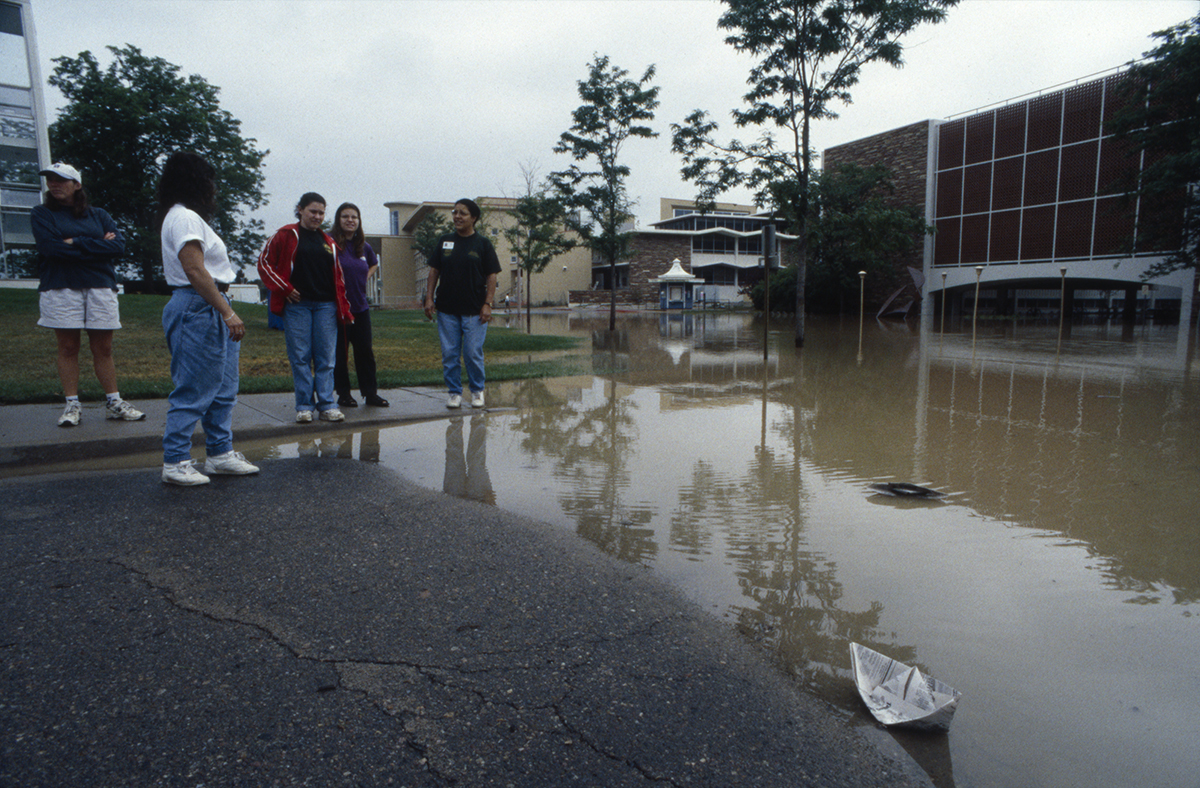

Hurricanes and tropical storms on the coasts tend to get countrywide airtime for their intensity and impact, but floods in the central part of the U.S. also cause significant damage and disruption. That is certainly true for the Front Range of Colorado. In 1864, a massive flood from the Poudre River destroyed the Camp Collins military post in LaPorte. In 1997, the Spring Creek flood caused $200M in damages and five deaths, when 10-14 inches of rain fell in a 31-hour period. Most recently, in September 2013, six days of historic levels of rain caused massive flooding in Northern Colorado’s Front Range.

“Floodwater damaged and destroyed homes and businesses, mountain towns and transportation networks, ditches, dams and bridges, oil and gas drilling sites, farmland, and natural areas across seventeen counties. Eight people lost their lives. This was a hydro-geologic event, as heavy monsoonal rainfall over many days produced both devastating floods and perilous landslides. State and local officials have estimated the monetary cost of the flood to be over two billion dollars,” notes Dr. Ruth Alexander, a professor in the history department and faculty researcher in the Public Lands History Center at CSU.

What can a historian do in response to life-threatening flooding? Quite a lot it turns out. By documenting the communication, cooperation, and activity of natural disaster responders, historians capture the knowledge and information-sharing process that is so crucial to future response and recovery.

Less than a month after the flood, Alexander and Patricia Rettig, head of the Water Resources Archive at CSU, had a conference call with Kevin Houck, section chief of Watershed and Flood Protection at the Colorado Water Conservation Board, to discuss the goals and funding for a public history project. Houck expressed keen interest in capturing the insights of professionals in water management, search and rescue, and recovery while the experience was still fresh in their minds. Alexander’s role would be to gather oral histories, recordings, and transcripts of extended interviews of people involved in an event.

While the flood prompted oral history projects in numerous counties, the oral history project led by Alexander and funded by the CWCB was the only one focused on emergency responders, water professionals, and officials responsible for flood management. She wanted to explore how and why the flood affected counties and communities in different ways, and how officials and professionals at all levels of government and in the private sector coped in the short and long term. While Alexander originally thought of this project as a resource for government officials and professionals in all areas of water and flood management, she also saw the materials as a resource for scholars, students, and researchers across the university. By making all of the materials publicly available through the Water Resources Archive at CSU's Morgan Library, the project would also be a resource for the citizens of Colorado to learn about "the choices communities can make to lessen their vulnerability to flooding," Alexander says. People need to be able to find, read, and use historical materials to keep their communities safe because “People are going to die if there is not good communication between professionals and the public,” Alexander says.

Collecting the Oral Histories and Materials

After securing funding, Alexander organized a team of history graduate students led by a recent CSU history master’s graduate, Naomi Gerakios (M.A. ’14). To help the students prepare to collect oral histories, the Public Lands History Center ran a full-day workshop on oral histories, including theory, methodologies, legal requirements, and best practices.

As the project manager, Gerakios set up the oral history interviews. “ I really enjoyed the interviews themselves: going to meet the individuals, hearing their stories, asking follow up questions beyond the standard list of questions we had outlined, and being able to make connections across the interviews themselves,” says Gerakios, a curator of collections for Heritage Village. “I was able to listen and identify similar themes across the interviews, identify comments that really stood out to me, and draw a broad picture of the flood from 34 different perspectives.”

Each oral history in the collection includes a transcript and an audio recording. Many also include an image of the interviewee. The resource collection as a whole includes 35 oral histories, images, newspaper articles, Powerpoint presentations given by Alexander to officials and other professionals around the state, articles, videos, and a final report.

Lessons Learned

Alexander's final report analyzes four main categories of lessons learned: floodplain management, preparation for and management during natural disasters, and recovery efforts.

In 2013, Fort Collins benefited from the lessons learned from the 1997 flood, which prompted improved flood basins, detention ponds, levees, and storm sewers, increased open space, a flood warning system for the city, and improved mapping efforts. Overall, Fort Collins had less property damage and lower repair costs than comparable cities like Boulder.

The 2013 flood caused some unexpected immediate and long-term problems. In the short term, for example, existing mutual aid agreements between cities were often too limited for new, catastrophic situations. In the days after the flood, city and municipality officials worked quickly and creatively with attorneys to draft all-purpose mutual aid agreements. According to Scott Sandridge, the Parks and Grounds superintendent for the City of Evans, one of these new agreements helped Greeley build a new pipeline to Evans, when Evans’ wastewater treatment plant became overwhelmed. The pipeline allowed Evans to send excess water to Greeley’s wastewater treatment plant which meant that Evans did not risk a raw sewage leak and did not have to call for a “no-flush” order for the city.

Communication during and immediately after the flood was also difficult. Bruce Holloman, who was the state emergency coordinator in 2013, had to work with FEMA, the US Army, the Civil Air Patrol, and the Colorado National Guard to gather information across the affected counties and then find ways to share that information with local communities. They used helicopters, satellite imagery, and photography as well as real-time GIS data to coordinate rescue efforts between national, state, and local groups.

Long-term recovery was complex as well. For example, much of the water for agriculture and cities in the affected counties moves through private ditches. According to Sean Cronin, the executive director of the Left Hand and St. Vrain Conservancy District, ditch companies were suddenly faced with millions of dollars of repairs, but many could not receive public assistance for those repairs.

City leaders like Tara Schoendiger, the mayor of Jamestown, had to meet with FEMA officials and physically walk them through damaged areas to show how the “private” ditches were in fact a crucial part of city water infrastructure.

Water ecosystems faced unexpected long-term threats, including overzealous repairs by individual land owners, volunteer crews, and local governments. According to Chris Sturm at the Colorado Water Conservation Board, “A lot of the debris in the stream channels was not trash...We didn’t anticipate the widespread removal of those materials and hauling it to landfills.” This led to waterways that couldn’t support fish populations and lost the ability to function as full ecosystems. Over time, however, Sturm and others at the CWCB have managed to develop nine new citizen-led watershed restoration coalitions to educate and guide restoration efforts.

Response, Recovery, and the Future

The lessons learned through these oral histories appeared again and again: communication, cooperation, and creativity. Town, municipality, county and state officials, and professionals shared stories of efforts to communicate and cooperate across jurisdictions. They repeated the need to be creative when disaster breaks the systems in place, threatening lives and businesses.

By sharing the knowledge gathered by people involved at all levels of government in planning, rescue, and recovery from the 2013 flood, Alexander hopes to provide insight and assistance to anyone interested in understanding and preparing for a flooding disaster along the Front Range. “It appears that I may be leading a new oral history project on the 2013 flood in 2019. The CWCB is very interested in interviewing large numbers of water professionals and others about lessons learned, problems identified, and improvements made since the 2013 flood,” Alexander says.