Photo: Professor Steven Fassnacht, Associate Professor Jonathan Carlyon, watershed science junior Lenka Doskocil, and natural resource management and Spanish senior Anthony Isham.

A mutual friend, a beer, and a river — all in Spain, 5,000 miles from Colorado — have brought together two CSU faculty members from very different fields, as well as a couple of their students.

A series of rather unlikely events conspired to create the fortuitous meeting and subsequent collaboration between Jonathan Carlyon and Steven Fassnacht. It has taught them that the humanities and sciences can enrich and inform each other, and provide students with a more complete and fulfilling educational experience.

Carlyon, an associate professor in the Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, and Fassnacht, a professor in the Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, had never met before 2016, but each of them had independently became friends with Spanish scientist Manuel Toro when Toro spent his sabbatical at CSU a decade prior.

Years later, when Toro learned that Fassnacht was preparing to take a group of students to study a river in northern Spain, he suggested that Fassnacht try “caelia,” a style of beer first brewed there about 5,000 years ago — before the Romans invaded the Iberian peninsula and instilled wine as the country’s preferred libation.

When Fassnacht searched the Internet for “caelia,” he came across a story on the CSU news website SOURCE about Carlyon’s research on the ancient brew. When Fassnacht told Toro about the article, Toro shared that he had become friends with Carlyon as well during his sabbatical at CSU.

“So when I got back from Spain in 2016,” Fassnacht recalls, “I knew that Jonathan and I had to get together for a beer.”

More coincidences

As it turns out, Carlyon started taking groups of his own students on trips to Spain in 2016, following the path of the Camino de Santiago, an ancient pilgrimage route leading to the shrine of the apostle Saint James the Great in Santiago de Compostela. One of the rivers that flows near that route is the waterway that Fassnacht and his students focused on during their Spain trips. Its water was a source for the ancient brewers of caelia.

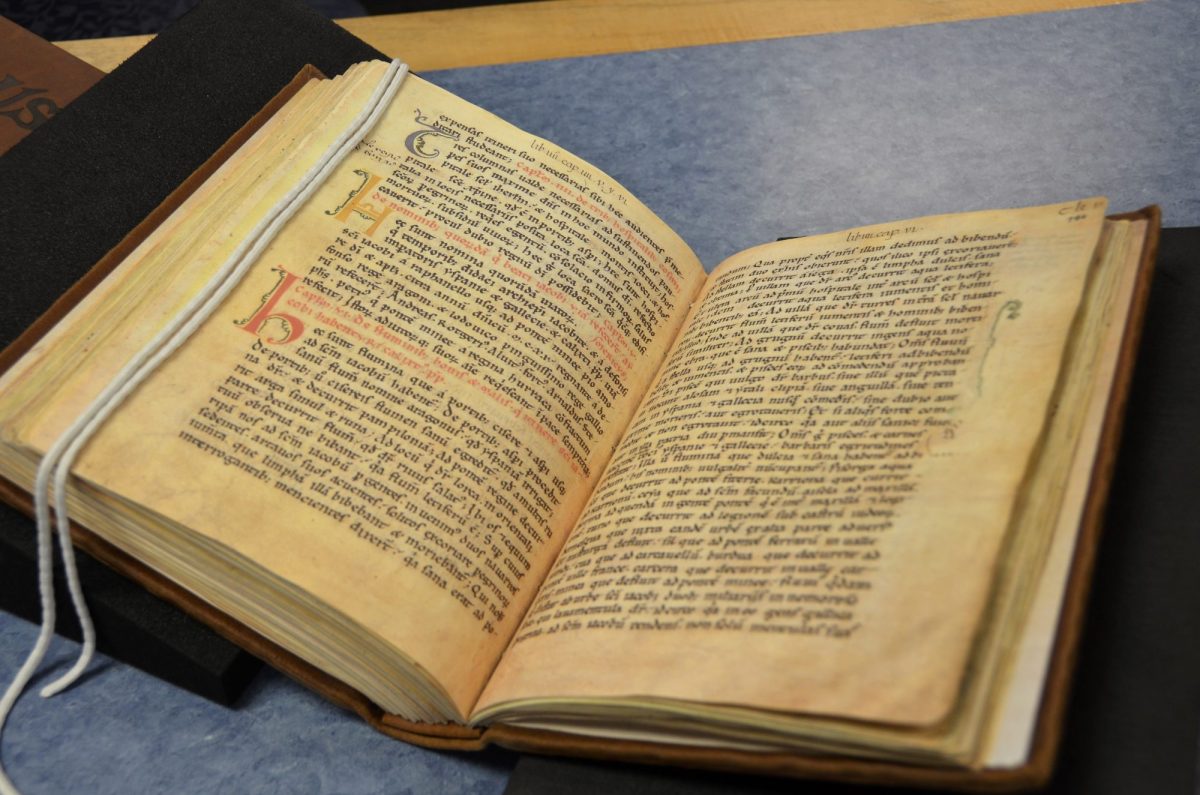

Enter Anthony Isham, who is graduating Dec. 2018 with a dual degree in natural resource management and Spanish. He signed up for Carlyon’s summer 2018 Camino trip and began discussions with Fassnacht and Carlyon about a possible capstone project that would blend the physical-science side of his degree with the humanities side. Around the same time, junior watershed science major Lenka Doskocil began collating data on the watersheds along the Camino for an independent study. Carlyon pointed them in the direction of the Codex Calixtinus, a 12th-century manuscript known as the Book of Saint James that offers background and advice to those making the Camino pilgrimage. The manuscript, a facsimile of which Morgan Library happens to have, contains a chapter titled “The Good and Bad Rivers of the Camino.” It offers guidance like the following excerpt about the “Salt Stream.”

“Be careful not to drink it or water your horse there, because the river is lethal. On its banks, as we were going to Santiago, we found two Navarrese sitting there, sharpening their knives, waiting to skin the horses of pilgrims which die after drinking the water. When we asked, they lied and said the water was safe to drink. So we watered our horses, and two died at once, which the men then skinned.”

A comparative project

For his capstone, Isham decided to analyze the chapter with the help of Carlyon, and perform some scientific measurements on the waters along the Camino with help from Fassnacht to determine how the ancient descriptions compare to the rivers’ conditions today. Doskocil identified each river crossing discussed in the Codex and searched for available water data.

“Anthony and Lenka were perfectly suited to integrate into what Steven and I were working on,” Carlyon says.

Prior to last summer’s Camino trip, Fassnacht took Isham to CSU’s GetWET Observatory, a monitoring site along Spring Creek. There he trained him how to use tools for taking river measurements such as flow rate, depth and turbidity, as well as detecting the presence of biological matter from plants and animals. Isham then employed those methods in the Ebro River basin along the Camino.

“There are a lot more people in Spain now, and that has affected the environment,” Isham says of his findings. “It was interesting to see how important the rivers are to these communities. It makes you feel like you’re part of history — you can definitely imagine the people being there after reading about it.”

And, he says, it’s still true that one shouldn’t drink from the Salt Stream. But now it’s for different reasons: Its waters have been tainted by upstream agricultural operations.

Bridging disciplines

Fassnacht and Carlyon said Isham’s project and their growing collaborations have resulted in some cross-pollination: Carlyon is incorporating more physical science into his teaching, and Fassnacht has added more of the humanities to his. Fassnacht’s education abroad trips now include a social-history component that he says “is often more easy to enumerate than the physical measurements that the students take.”

“We are developing terminologies that are appropriate to both disciplines,” Carlyon says. “I’ve learned that we can begin a dialogue with our friends in the sciences, and we realize we have more in common than we ever imagined.”

Carlyon and Fassnacht now refer to things like the Codex chapter on rivers as “metaphorical core samples.”

“I now see these core samples in the literature and historical art components,” Fassnacht explains. “We’re not just meshing disciplines but blurring them, and we want to come up with new ways to blur what they are. It just makes students more well-rounded.”

“Students like to do stuff and get their hands dirty, and the humanities offers that when it’s transdisciplinary. What keeps me and Steven going is this intellectual coincidence that just keeps building.”